A few weeks ago, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that the U.S. poverty rate fell a half percentage point – from 12.3 percent in 2017 to 11.8 percent in 2018. Yet even as poverty declined nationally, growth in median household income stagnated and inequality is the highest on record.

The results are similarly mixed in New York City. In our city, robust economic growth combined with progressive policies designed to help low- to middle-income households have led to reductions in poverty and increases in median incomes. However, enormous structural inequities exist, such as gaps in median income by race and ethnicity, and income inequality in the city did not budge.

This new data from the U.S. Census Bureau is a call to action. It’s up to policymakers build on the policies that can fuel more positive outcomes for New York City families and to reject policies that would reverse progress.

To understand what policymakers need to do, we need to better understand the data.

The city’s poverty rate declined from 18 percent in 2017 to 17.3 percent in 2018 – nearly 2 percentage points below the poverty rate in 2006, prior to the Great Recession.

While any reduction is meaningful, New York City’s poverty rate is more than five percentage points higher than the national rate, and the child poverty rate is seven percentage points higher.

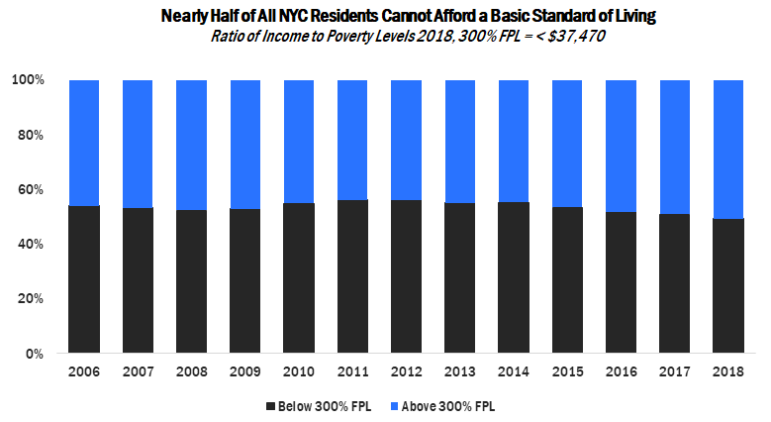

To be sure, the national poverty rate – a woefully inadequate $12,490 a year – is itself a low bar, falling well short of measuring the income required for a basic standard of living. Applying a more sensible yardstick – 300 percent FPL or $37,470 annually – the data reveal that the share of individuals living above this threshold was 50.7 percent in 2018. That is, half of all New York City residents cannot afford a basic standard of living.

For the second straight year, median household income grew in New York City – a 2.3 percent increase ($1,436), even stronger than the 1.3 percent growth in 2017.

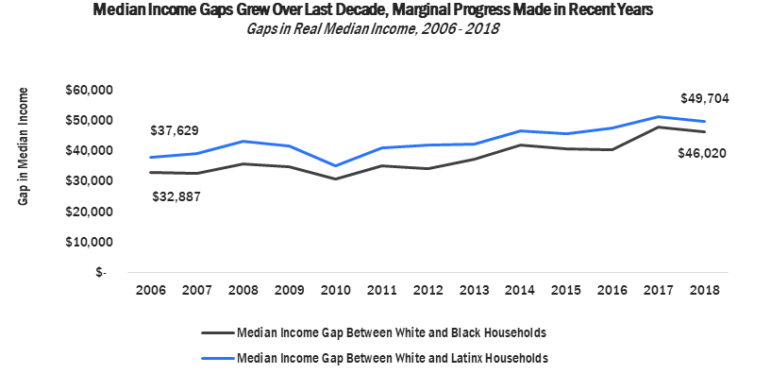

As expected, New York City’s minimum wage increases have translated to higher earnings, particularly for people of color. From 2017 to 2018, Black workers saw an increase of 4.3 percent ($1,995) and Latino workers saw an increase of 3.5 percent ($1,508).

While new data find progress towards closing income gaps, the median income for White households in 2018 ($94,162) was nearly double that of Black households ($48,142) and more than double that of Latino households ($44,458). These persistent disparities reflect centuries of structural inequities and discrimination that persists today in education, hiring, and other areas.

Policies advanced in New York City and State – such as the minimum wage increase and universal pre-k – have meaningfully reduced hardship and addressed economic injustices, but local policymakers cannot carry the burden alone.

Washington can take action now.

First, ahead of the November 21st deadline to keep the federal government open, Congress can right-side a decade of federal budget austerity – which has resulted in the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in federal aid to New York City – by following the priorities established in the House spending plan.

Secondly, some members of Congress are considering extending or expanding tax breaks for businesses, even though the 2017 federal tax law was largely tilted in their favor. Any tax package passed this year should also help working people and kids by expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit: two proven policies that reduce poverty and improve economic opportunity.

And in the long term, Congress should advance policies like the Working Families Tax Relief Act, which would further expand the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit, and reject policies like the ones contained in President Trump’s budget and regulatory proposals, which the deficit-financed 2017 federal tax law, with all its giveaways to powerful individuals and profitable corporations.

Derek Thomas is the Senior Fiscal Policy Analyst and Gaurav Gupta-Casale is a Fiscal Policy Associate at the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies.