Adi Talwar

Joseph Wasserman (88) leaving the Inwood Senior Center located at 84 Vermilyea Ave in Manhattan. Inwood is one of the rezoning neighborhoods where senior housing is a topic of discussion.

Staten Island resident Dahlia Rivera says she can’t leave her Mitchell Lama apartment complex, where her rent is restricted, because she wouldn’t be able to afford anywhere else. It’s frustrating, says the retiree who worked in civil service for 30 years, because she has a child in Virginia and it’s also a steep climb up a hill to her apartment. Still, she calls herself lucky: She knows seniors who are forced to live with relatives with whom they don’t get along, and she’s noticed the older homeless people at the ferry terminal.

Unless the city’s proposed Bay Street rezoning comes with affordable housing for seniors and other low-income Staten Islanders, she says, “They’re going to be pushing out people. You’re going to have more people living on the street.”

Up in the Bronx, Carmen Vega-Rivera, a disabled, retired arts educator and an organizer who opposes the city’s Jerome Avenue rezoning, is also worried. Once her husband retires, their income will be slightly above the cut-off for the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption, a rent-freeze program for low-income seniors, but they face growing medical expenses. Furthermore, her landlord is undertaking many building-wide renovations, and while Vega-Rivera is happy to see the elevator repaired, she’s afraid those costs will be permanently tacked to her rent bill in the form of a Major Capital Improvement rent increase.

“I can’t afford an increase on my existing rent, whether it’s directly because of the rezoning, whether it’s because of Major Capital Improvements or anything else, because that’s going to put me at a level where I have to make choices to have a roof over my head. Where else do I cut?” she says.

While the city’s significant citywide investments in senior-specific housing are beneficial to all seniors, it remains to be seen how much housing designated for seniors, and affordable to seniors, will end up in each rezoning neighborhood, and to what extent it will mitigate any risk of their displacement.

Furthermore, the planning processes in rezoning neighborhood are delivering some additional services and programs for seniors in disinvested communities, but not always as much as advocates would like.

Then again, rezoning neighborhoods are not the only ones seeking a piece of the city’s steadily growing, but still small budget for senior services.

Heightened risks

Some senior citizens worry that, if a rezoning risks exacerbating market pressures, their age group will be among those most vulnerable to displacement.

As City Limits reported in a three-part series on the aging in 2015, New York City’s seniors face particularly severe challenges when it comes to housing. Six in 10 senior renters are considered rent burdened, paying more than 30 percent of their income towards rent, compared to five in 10 in the general population, according to a 2017 report by Comptroller Scott Stringer.

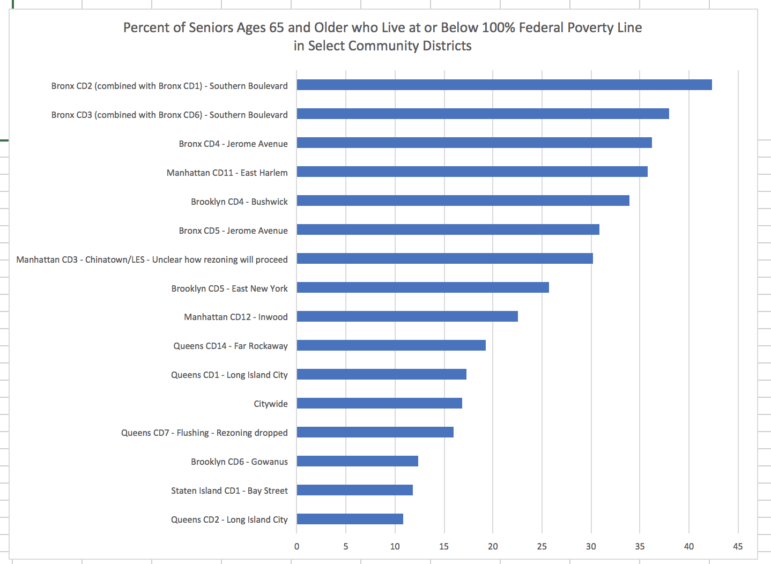

The problem is not just that rents are going up: Those who make up the city’s elderly are increasingly low-income. While senior poverty decreased in the rest of the country from 1990 to 2015, poverty rates among New York City’s elderly grew from 16.5 percent to 18.1 percent from 1990 to 2015, according to the Department of the Aging’s 2017 Annual Plan Summary. Minorities make up a growing percentage of New York City’s seniors, and they are poorer than White seniors, who have an average median income of $47,500 in 2015. Among Black seniors, the median income was $33,917, while Latino seniors made $17,500, and Asian $27,500 in 2015.

In 2011, the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University estimated that nationwide, only 36 percent of income-eligible seniors received the rental assistance they qualify. As earlier reported by City Limits, a 2016 study by LiveOn found that as many as 200,000 New Yorkers may be on waiting lists for senior housing. And the competition for affordable senior housing will only increase as the baby boomer generation ages and as more aging New Yorkers opt to live in an urban environment.

On the one hand, rezonings could be seen as an opportunity for seniors to receive the help they need, especially when it comes to housing. The mayor has twice amped up the number of units in his housing plan dedicated to seniors. That allotment increased from 10,000 in the original 2014 housing plan to 15,000 in February 2017 and then to 30,000 last October. While these units will be spread throughout the city, the rezonings can create opportunities for the construction or preservation of senior housing in some of those neighborhoods. For instance, the East Harlem rezoning effort includes the redevelopment of the 111th Street ballfields with 650 rent-restricted units, of which 79 were designated for seniors.

Furthermore, the mayor’s neighborhood rezonings have each come with multi-agency investments. The neighborhood planning process that take place in conjunction with each rezoning represents an opportunity for neighborhoods to speak out about what senior services they need.

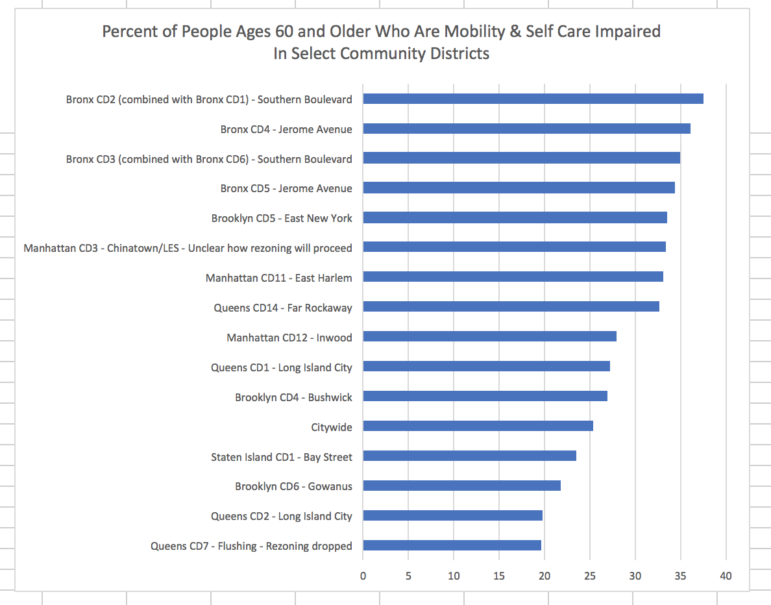

On the other hand, critics of rezonings have often raised concerns that the mayor’s mandatory inclusionary housing policy, which requires a portion of new development in rezoning areas to be affordable, does not require private developers to build housing affordable to people who only receive Social Security income. There are also concerns that seniors would find relocation particularly challenging, given the dependency of seniors on local networks of friends and services and the health impacts of displacement.

In the eyes of critics, it is a moral imperative that the city ensures seniors are not displaced from rezoning areas due to increased market pressure.

“They built our infrastructure, led social-justice movements, made major advances in healthcare and technology and fueled our thriving economy,” says the East Harlem Neighborhood Plan, which was crafted by residents and organizations that sought to influence the city’s rezoning process. “Older East Harlem residents are a part of this legacy and are key to preserving the history and culture of the community.”

Policy staff at LiveOn New York, the city’s leading advocacy organization for senior rights, did not make a pronouncement about whether the rezonings would do more harm than good for seniors or vice versa, but said that they’ve been working to make sure the concerns of seniors are heard in rezoning neighborhoods by, for instance, hosting a discussion about senior issues in the Jerome Avenue rezoning area that included the Department of City Planning, Councilmember Vanessa Gibson, and community members.

“We always want to make sure that policymakers and key decision makers hear that voice,” says Cianfrani.

Numerous citywide housing initiatives

Seniors in rezoning neighborhoods will be affected by changes in their own neighborhoods, but also by the administration’s citywide initiatives to address the senior housing crisis.

“Seniors First,” the administration’s expanded senior-housing initiative announced in October, aims to build or preserve a total of 30,000 such units by 2026 through three new initiatives: making 15,000 apartments more senior-accessible in buildings the city preserves, developing 4,000 new senior apartments, and investing in the preservation of 6,000 properties built with Section 202, the federal program that at one time was responsible for the construction of much of the city’s senior housing. This is on top of the roughly 5,000 senior units that the administration had completed by that October.

The city’s program for constructing new senior units is the Senior Affordable Rental Program (SARA), which serves seniors making up to 60 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI), or $40,080 for a single person. Developers are also allowed to include a tier of units for seniors making up to $60,120 for a single person, and 30 percent of the units must be reserved for homeless seniors. Developers that apply for the SARA subsidy are asked to “provide a plan, budget, and funding source” for senior services, though on-site services are not required and can vary depending on the project.

While the city’s other low-income housing programs do not require units for seniors, they do encourage developers to include “supportive housing units or to create intergenerational housing by incorporating senior housing units.” LiveOn NY policy staff say they’ve heard that developers are catching on and increasing the number of units in such projects for seniors.

In addition, the city says its Zoning for Quality and Affordability text amendment, which reduced parking requirements and allowed higher buildings for developers who commit to building senior housing, has helped to spur senior housing development while also fostering more walkable streets with ground-floor retail that are beneficial for seniors. The city has also created a new guidebook recommending how building owners can renovate their buildings to allow aging in place.

“We are really pleased with the direction that the mayor has taken, particularly with housing,” says Cianfrani. “We’re really encouraged and our role is to continue to build relationships with the city agencies that are going to be building these programs.”

Beyond the 30,000 senior units to be built and preserved, the de Blasio administration has invested in other efforts to protect seniors from displacement. In 2014, the state and city raised the income eligibility level to $50,000 for the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE) program (now rebranded “New York City Rent Freeze Program). Since City Limits last reported on the program in 2015, enrollment rose from about 50,000 out of about 122,000 eligible seniors to 50,524 seniors in 2016 and down to 53,089 seniors in 2017. The Department of Finance says the fluctuation is to be expected due to deaths and other changes in living situations.

In addition, the city’s Senior Citizen Homeowner’s Exemption program (SCHE) provides low-income senior homeowners with property tax exemptions. After pressure from the de Blasio administration and advocates, the state finally raised the household income eligibility level from $37,399 to $58,400 last summer, which the city estimates will benefit about 32,000 more households. The city has also sought to help seniors who qualify for this exemption with water bill assistance, and has partnered with the Parodneck Foundation to launch the Senior Citizen Home Assistance program to fund home repairs. And while the city’s guarantee of a right to counsel for all low-income tenants in housing court benefits all tenants regardless of age, senior advocates see it as a particularly vital policy for the elderly.

Advocates still see room for improvement. LiveON and the Comptroller’s 2017 report have also called for the state to set up an “auto-enrollment” system for seniors eligible for SCRIE, as well as changes to the program to ensure that seniors’ rents are frozen not at the rent at the time they apply to the program, but at 30 percent of their income.

Both LiveON and Councilmember Margaret Chin, who heads the Council’s Committee on Aging, would like to see the city create a stable funding source for service coordinators in new senior housing developments; right now it’s left up to senior housing developers to find a way to support services, whether through other government financing programs or other avenues.

Advocates would also like to see the city provide higher funding levels to the Department of the Aging (DFTA) to expand a number of existing support services for seniors.

While the de Blasio administration increased DFTA’s budget from about $264 million in FY 2014 (the last year of the Bloomberg administration) to about $372 forecast for FY 2018, LiveOn New York has consistently called for higher levels. DFTA funding made up a miniscule .4 percent of the FY 2017 budget, though Chin notes that the Council secured a roughly $23 million increase in baseline funding last year.

Visions in rezoning neighborhoods

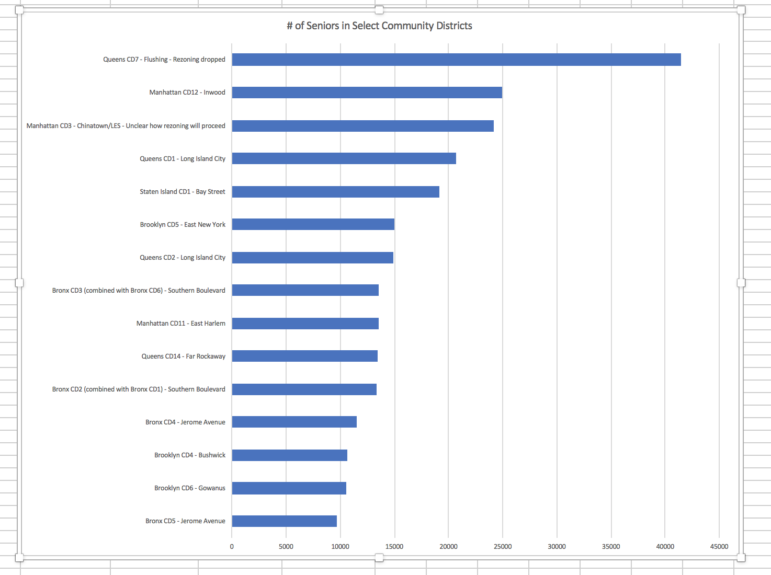

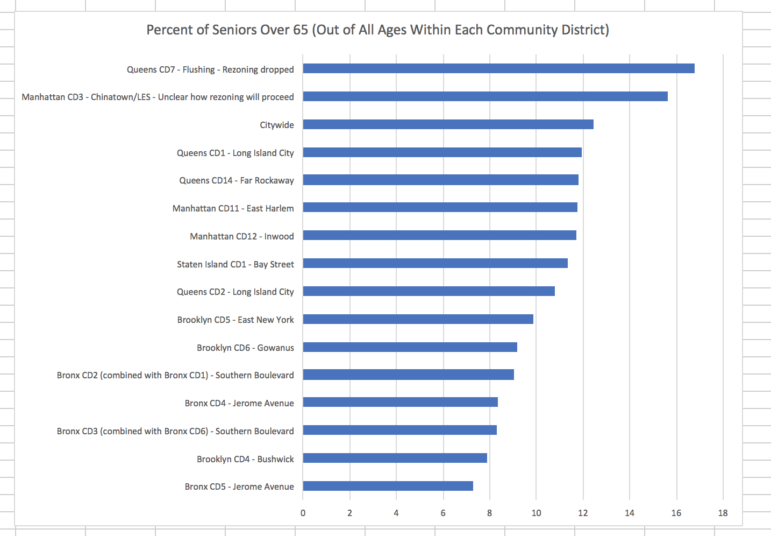

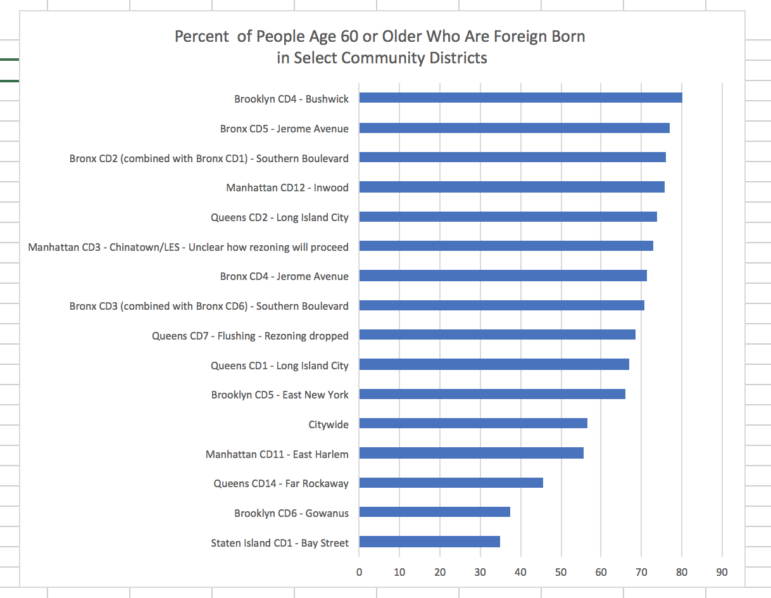

The community districts that overlap with de Blasio’s proposed rezonings vary in their number of seniors, and generally have a below-average percentage of seniors when compared to the rest of their populations, according to information culled from the Department of Aging’s 2017 Profile of Older New Yorkers, which mostly relies on 2011-2015 census data. Many of the districts, however, are home to some of the city’s most vulnerable seniors, with high rates of poverty and many who are foreign born.

In many of the neighborhoods undergoing a rezoning, community advocates have called on the city to make investments in the needs of its elderly. Each of the rezoning plans passed so far do include investments in seniors, though not always all the ones requested—and not always enough to ameliorate the concerns of some advocates that seniors could be displaced by exacerbated market pressures.

The Coalition for Community Advancement in East New York and Cypress Hills demanded that the city invest in accessible subways and senior centers as part of its East New York neighborhood plan. At the time the rezoning passed in April 2016, the city did not commit to those two asks, but it did agree to help senior homeowners gain access to funding for repairs through the Senior Citizen Home Assistance Program (SCHAP) as well as home water assistance. The city’s June 2017 progress report for East New York says that two low-income seniors received $58,745 through the Senior Citizen Home Assistance Program for a variety of repairs and that the city had made playground improvements to accommodate East New York seniors.

But the coalition’s Darma Diaz says she is concerned that not enough affordable units are being created at levels that seniors can afford to rent. She also says that despite increased attention from the city, senior homeowners are still being swindled and losing their mortgages. She’d like to see an increased investment in existing senior centers, better SCRIE outreach and a larger tax break for property owners who rent to seniors with SCRIE. “It doesn’t matter whether they raise the program [income] qualifications if, A, our seniors don’t know about it and, B, the property owners [renting to seniors] are close to nonexistent,” she says.

A report released last fall by Center for NYC Neighborhoods described the many challenges faced by East New York homeowners and especially senior homeowners, including the challenge of accessing loans—even through the SCHAP program—as well as the prevalence of predatory brokers who seek to trick seniors to sell for a low price (the city and advocates are currently trying to stop such activity through the establishment of a cease and desist zone).

In Far Rockaway, when a coalition of advocates requested that the city look at the area for redevelopment, they called for more senior services throughout downtown. The city’s final list of investments related to the Downtown Far Rockaway rezoning does not mention seniors specifically, but does include investments in bus shelters, in a car-sharing pilot program, in ADA access ramps at the local police precinct, and in other amenities that might benefit seniors.

The East Harlem Neighborhood Plan’s section on “Health and Seniors” recommended accessibility improvements to parks, priority for seniors for affordable housing, improvements to the Access-a-Ride system, more bus shelters and sidewalk benches, and other suggestions. At the time the rezoning passed in November, the city agreed to site more benches and invest $18.1 million in intergenerational playgrounds. The city also notes that its efforts to develop affordable housing and protect tenants will help seniors. An environmental impact statement for the rezoning mentions the local implementation of a citywide program to help combat senior isolation and highlights that East Harlem already has seven senior centers as well as an “Innovative Senior Center,” with enhanced resources.

David Nocenti of Union Settlement said that, overall, he was impressed by the city’s many commitments to East Harlem, which cover a range of neighborhood needs, and wasn’t sure it made sense to singularly analyze only the investment in senior initiatives. The real question to be answered in time is whether the city fulfills all its commitments, he said.

In the case of the Jerome Avenue rezoning, which was approved by the City Council Land Use Committee this week, the city promised investments in the creation of a senior housing development on public property within the rezoning area. The city’s draft neighborhood plan also mentions that its tenant protection initiatives and the SCHAP program can also benefit seniors. Still, Vega-Rivera, who lives near the Jerome Avenue rezoning, remains skeptical that the city’s ramped up investments in affordable senior housing are sufficient to protect all seniors in the area. “It’s like, if there are 100 seniors and you’re saying we’re going to give housing to 15 of them, where do the other 85 go, how do they survive?”

Meanwhile, in Inwood, the next rezoning up for a vote, the city has committed to initiatives like outreach to promote SCRIE and inform tenants of their rights. A new plan by community groups called Uptown United calls for a 10 percent senior set-aside in new affordable housing.

In all five of these areas, it’s not yet clear exactly how many units created as a result of the rezoning will end being designated specifically for seniors—or how many will end up being affordable to the many seniors who live below the poverty line in these neighborhoods. Apart from the rezoning, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development from 2014 through 2017 has financed 258 senior units in Brooklyn Community District 5 (where the East New York rezoning took place), 154 senior units in Queens Community District 14, (which contains the Downtown Far Rockaway rezoning), 242 senior units in Manhattan Community District 11 (East Harlem), 62 senior units in Bronx Community Districts 4 and 5 (Jerome Avenue) and none in Manhattan Community Board 12 (Inwood).

Needs extend beyond rezoning neighborhoods

Of course, it’s not only rezoning neighborhoods where seniors are seeking more services and senior-targeted housing. Nuanced conversations are necessary to understand what areas should be prioritized for the limited funding of DFTA and other agencies.

Take Flushing, in Queens Community District 7, where a rezoning under consideration was dropped. That community district actually has a large number of seniors, and during the rezoning discussion, community advocates with the Flushing Community Rezoning Alliance demanded more senior centers and better SCRIE outreach.

In Chinatown/Lower East Side, where there are also a large number of seniors, developing under the existing zoning is the cause for concern. Advocates are worried about the impact of private development on seniors who live by the Lower East Side waterfront, with one developer planning to construct a skyscraper on top of an existing, 10-story senior building. The De Blasio administration has long rejected the Chinatown Working Group’s rezoning plan, which would have covered a large area and prevented skyscrapers along the waterfront, though it has agreed to work with the community board for a limited study of Chinatown (though no progress has yet been made on that study).

According to Paula Segal, an attorney at the Urban Justice Center Community Development Project, it remains unclear how many seniors will have to be relocated during the construction of the skyscraper—the developers said last year that 10 units would be permanently displaced and nine vacated temporarily—or how the seniors will be impacted by neighborhood changes as new, wealthier residents move in to the area.

The relocation plan for the seniors requires HUD approval. The developer also needs certain zoning modifications that are contingent upon the City Planning Commission’s approval.

Chin says she’s also concerned for these tenants and the fact that they recently lost their supermarket due to the development of the nearby Extell tower. In addition, she says that any future planning for Chinatown needs to take into account the many seniors who live in five-story walk-ups and want to age in place by constructing more senior housing and senior centers.

It’s true that rich or poor, all New Yorkers generally need new types of services as they age, and in some middle-income or affluent neighborhoods there are many seniors but a lack of senior services. The 2017 report by Comptroller Stringer highlights the mismatch between areas with the most seniors and areas with the most services, noting, for instance, that three eastern Queens neighborhoods and southern Staten Island each have “relatively large senior populations but few senior centers.” None of those neighborhoods include rezonings, and with the exclusion of Bensonhurst, all those neighborhoods all have below-average levels of senior poverty.

The Comptroller’s report does call for the expansion of particular senior initiatives in three neighborhoods with larger senior populations where rezonings are also under discussion, arguing that Staten Island District 1 (which overlaps with the proposed Bay Street rezoning) should be included in the Safe Streets for Seniors program, and Manhattan Community District 3 (Chinatown/Lower East Side), and Manhattan Community District 12 (Inwood) should be included in the Age-Friendly Neighborhoods Program, a community-based planning effort that engages seniors to come up with an action plan for how to improve services in their area.

When it comes to where to prioritize outreach to get seniors to sign up for the SCRIE program, the Department of Finance says its focusing on neighborhoods where in 2014 it found the highest number of eligible seniors not using the program. Among the top ten neighborhoods they are targeting there is one, Highbridge/Concourse that overlaps with a rezoning (Jerome Avenue). But according to LiveOn’s 2015 analysis of under-enrollment of eligible seniors in SCRIE East New York, East Harlem, the North Shore of Staten Island, also had very high percentages—over 71 percent—of eligible seniors not enrolled.

The comptroller’s office says the point is not that there must be a proportional number of senior amenities to seniors, but rather than the city has “not clearly articulated how they plan to respond to the changing demographics of the City on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis or undertaken an analysis of the resources needed to better serve an older population.”

A few months after the release of Stringer’s report, the city’s Age Friendly NYC initiative, a decade-long effort launched by the mayor’s office, the City Council and the New York Academy of Medicine in 2007, released a new report including 86 initiatives, some old and some new, aimed at expand the city’s services for seniors. One of those initiatives seemed to acknowledge the Comptroller’s concerns: the city will work with partners to create an interactive map that will “facilitate more informed planning and more equitable and localized deployment of resources for older people.”

The charts below show statistics for each of the community districts that have been discussing or have discussed a rezoning proposal under the de Blasio administration and that we follow at Zonein.org. For each, we’ve noted the relevant rezoning: some rezonings run through parts of two community districts, and some rezonings are far smaller than the size of the entire community district. The Department of Aging’s data also combines certain community districts so that there are 55 districts total instead of 59.

4 thoughts on “Rezonings Carry Opportunities and Risks for Low-Income Seniors”

Pingback: News (March 2018)

Pingback: Tenants Are Fighting Eviction Before It Starts – TCNN: The Constitutional News Network

Pingback: Tenants Are Fighting Eviction Before It Starts | Make the Road New York

Pingback: June 14, 2019 – Weekly News Roundup - New York, Manhattan, and Roosevelt Island | Manhattan Community Board 8