HOLC

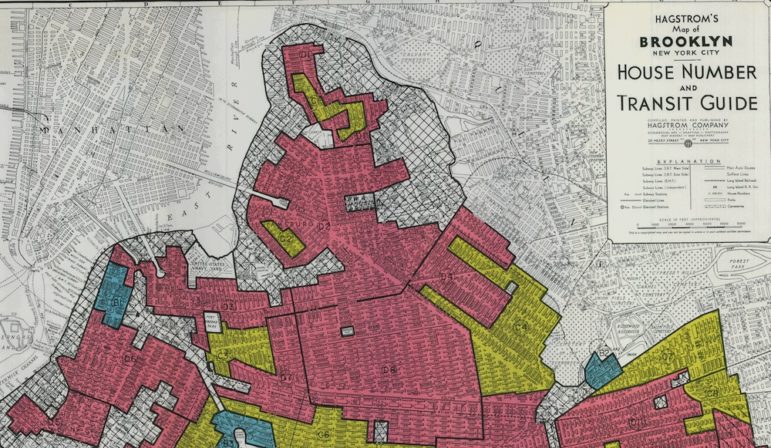

A redlining map of Brooklyn.

Editor’s Note: The following op-ed discusses the city’s “community preference” policy, which requires that when affordable housing is developed, residents of the local community district receive preference for half the units. The policy is currently facing a court challenge.

On August 1, New York Daily News columnist Errol Louis wrote an essay entitled “Perpetuating a Segregated City.” The main thrust of the article was how perverse the city’s lottery system was by including and excluding the wrong people, thus perpetuating segregation. “Black New Yorkers make up about 23% of the city’s overall population, but are less than 5% of the population in 17 of the city’s 59 community boards.” He goes on to similarly compare the distribution of Latino households – 29% and 10% respectively.

On August 10th the editorial board of the Daily News picked up the mantle, explaining that an NYU student moving into an apartment in Hell’s Kitchen and living there for one week has a better chance of getting to relocate to a better apartment in Chelsea than a black family from Canarsie. A hyperbolic and unlikely scenario, but not any less than the more than 10 percent of text devoted by Louis to the hypothetical household in need of affordable housing, but living one block outside of a community district containing a desired housing project. At least the main thrust of the Daily News Editorial was the highly questionable and successful efforts of the de Blasio Administration to prevent the public from seeing the results of a study commissioned as part of a Fair Housing lawsuit. That position is spot on. For a self-proclaimed “progressive” administration to be either afraid of refuting a flawed study or afraid of the truth is a betrayal of core progressive attributes. Release the study.

But the study notwithstanding, this entire argument misses the point, the point being that for over 150 years blacks and other minorities (mostly minorities of color) have been excluded from substantial residential areas throughout the country. Race based zoning was prevalent in the South after reconstruction until overturned by the Supreme Court in 1917. But even then, these same municipalities employed professional planners (many from the North) who assisted cities in using planning rationale devoid of explicit racial animus, but still in the “service of apartheid,” to quote urban planning scholar Christopher Silver.

Add to this the pervasive use of racially restrictive covenants (not fully outlawed until 1968), redlining, which deprived people of color, and particularly blacks, of an important wealth-building opportunity when this country’s economy was more equitable and our primacy in the global economic arena was unchallenged, and urban renewal, which displaced hundreds of thousands of blacks and other minorities from redlined areas, further concentrating them in remaining redlined areas. For the most part, these same redlined areas happen to be the subjects of the current debate around community preferences in lottery systems.

Are the current preference systems fair? Are they rational? No. It is very hard to justify community preferences on the basis of a community district boundary. It is even hard to justify it on the grounds that local residents should have preferences just by the fact that they reside there, especially since the greatest opportunities for creating affordable housing through cross-subsidization by market-rate units are precisely in those areas where gentrification and displacement has already taken hold, thereby already having excluded many (as urban renewal did) from any new housing opportunities arising from new development. But to simply argue that local preferences should be eliminated without a countervailing demand that the city affirmatively, deliberately, and aggressively seek to rezone and finance new construction of affordable housing – affordable to the very people being displaced elsewhere – in low rise, affluent (and yes) white neighborhoods is the height of irresponsibility.

But even that, though a more responsible position than one that simply seeks to scrap preferences, would be unworkable. Having worked in neighborhoods of this city for over 40 years, neighborhoods traditionally labelled as the “inner city,” most people I know prefer to remain in the communities that they know, want to be part of any improvement, and want to benefit from any such improvement, in terms of economic opportunity and quality of life. Simply placing people in areas where a cup of coffee costs $4 instead of $1, or where restaurants as so expensive that one meal for a family could amount to a weeks’ net pay, is absurd. But to exclude people from opportunities for improved housing in the very neighborhoods that were the only neighborhoods they were permitted to live in for many generations does not only belie arguments made on fair housing grounds, but represent a modern-day racist approach to housing redevelopment, not unlike the racist approaches of racial zoning, restrictive covenants, redlining and urban renewal.

A more equitable and rational system would be to redraw all of the redlined areas of this city and provide preferences in new developments for those residents who have either lived there continuously for at least five years or have been displaced from those redlined neighborhoods over the past ten years. This would be a very small, but not insignificant approach to redressing the private and government-sponsored racist policies and programs that have so disadvantaged such a significant part of our citizenry over the past one and one-half centuries. Beyond that, people should be free to live wherever they choose. Unfortunately, formal freedom is not the same as substantive freedom, and until it is in this country, we need to redress wrongs when and where those opportunities present themselves. And, if in the process, those with choices are placed at a disadvantage compared to those with historically-enforced and reinforced deficiencies in choices, then this is an outcome that justice, equity and simple morality demands.

Harry DeRienzo is president of the Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association.

2 thoughts on “CityViews: Missing the Target on Segregation”

Nothing wrong with the community preference policy. Why not give local residents a chance to stay in their own neighborhoods near family and friends? It also builds political support for ‘affordable housing’. The entire deBlasio ‘affordable housing’ scheme will end up costing NYC taxpayers billions but that’s a separate issue.

Within 10-15 yrs the only apts in Mahattan inhabited by families with annual incomes under $40K, will be in city owned properties (projects)…

and the city has started to bring in private management and eventually private ownership of all city owned properties.