HUD

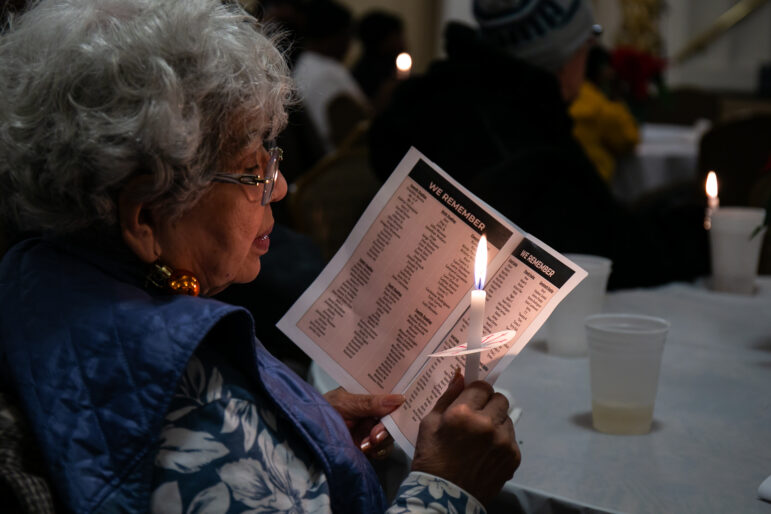

The demolition of a building in the Pruitt-Igoe public-housing development in St. Louis.

In the era of Trump, even cliches will offer no solace. “There is no ‘doing more with less,’ which we’ve done every year for more than 15 years,” NYCHA chairwoman Shola Olatoye told a City Council budget hearing on Monday. “So there will be tough choices ahead.”

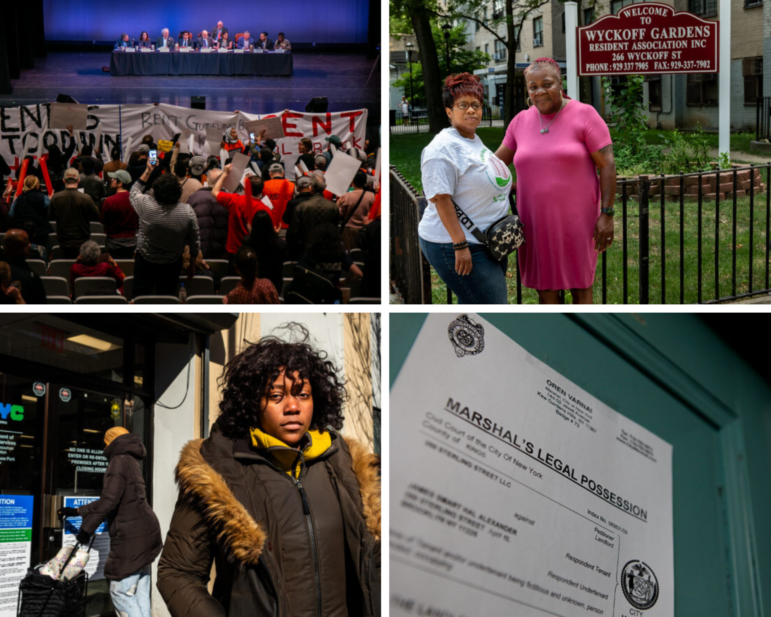

The federal government’s starvation of public housing has been the backdrop to policy discussion about NYCHA for a decade. But the likelihood that this year’s $35 million in reduced support is just the beginning of the damage that will occur lent Monday’s hearing a particularly dire tone.

“The presidency of Donald Trump represents the greatest challenge to public housing and Section 8 in the 82-year history of the New York City Housing Authority,” Councilmember Ritchie Torres, a Bronx Democrat who chairs the committee on public housing, told the room. “Were all of these cuts to take effect it would cripple the core operations of the housing authority and change life in public housing as we know it,” he added. “The loss of hundreds of millions of dollars in funding runs the risk of creating a financial and physical death spiral from which NYCHA might never recover. What is at stake is nothing short of the survival of public housing.”

NYCHA Chairwoman Shola Olatoye didn’t disagree. She called on the Council to join NYCHA in lobbying Washington to stop the cuts—a long shot at best, given how isolated the public-housing constituency is. She also said, “As a city, we need to decide what level of service in public housing we can tolerate,” and discussed in detail that challenges she’s faced at getting NYCHA’s workforce to serve tenants after 4:30 p.m. or on weekends. She also stressed that the new plan for dealing with the Trump administation cuts is the same NextGen plan that NYCHA has been implementing for two years by collecting more rent, modernizing technology, streamlining management procedures and developing “underutilized” land to create affordable or mixed-income housing—an approach that Olatoye characterized as a “win-win.”

Torres sought more. He wanted an answer to the Big What If—as in, what if Washington delivers a budget blow that surpasses the capacity of NextGen? “I just want to have a clearer sense of what the worst-case scenario looks like,” he said. “I know it’s partly speculative, but I think people should know how bad it could get.”

“The dismantling of public housing has happened in other parts of this country. We don’t have to look far,” Olatoye answered. “St. Louis, Chicago. Buildings disappear. People are dispersed. So that is not a future that I think this city wants. … I believe that’s the worst case scenario.”

The two cities the chairwoman mentioned are, indeed, places that have seen once massive public-housing systems shrink to mere shadows of their former selves. To critics of public housing, names like Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis or Cabrini Green in Chicago are all the proof one needs that government-operated housing is doomed to disaster. The reality is public housing writ large is an incredibly complex story of failure and success—encompassing ill-fated design fads as well as solid construction, healthy communities amid racial segregation, noble ideas and fiscal sabotage. The sagas of St. Louis and Chicago are themselves unique and complicated.

For New Yorkers who want to familiarize themselves with the worst-case scenario to which Olatoye referred, here’s a reading and watching list.

Chicago: After spending several years in federal receivership in the 1990s, the Chicago Housing Authority undertook its Plan for Tranformation in 1999, which among other things called for the demolition of 25,000 units of public housing:

St Louis famously demolished the Pruitt-Igoe development in 1972 and demolished its last public-housing high-rise in 2014:

4 thoughts on “Worst Case for Public Housing Seen in 2 Midwestern Cities”

NYCHA is a bottomless money pit funded by the NYC taxpayer.

I’m afraid that’s not true. City money comprises a mere 2.5 percent of NYCHA’s budget. Tenant rent makes up a third of the budget, and federal subsidies pick up about 57 percent of the tab. Is it a money pit? NYCHA provides housing to at least 488,000 New Yorkers (and probably more), providing stability that keeps people out of homeless shelters, hospitals and even jails or prisons that cost the taxpayer a heck of a lot more. Look at it this way: NYCHA houses a city bigger than Atlanta for $2 billion less than it costs the NYPD to operate a force of 35,000.

NYCHA is a bottomless pit of safety and stability for many who cannot otherwise afford that.

Many businesses are subsidized indirectly by NCHA. When businesses do not pay wages to cover rent and minimum standards of dignity, NYCHA can help those businesses maintain a healthy and stable workforce by providing subsidized housing. Many city workers on lower salaries live in NYCHA buildings. Many others work in private sector. For decades NYCHA accepted as residents only those who had good work records or were disabled or retired .

Thanks to Jarrett Murphy for consistent and outstanding reporting on the place where I live in peace and, hopefully, security.

what can residents of NYC do about this