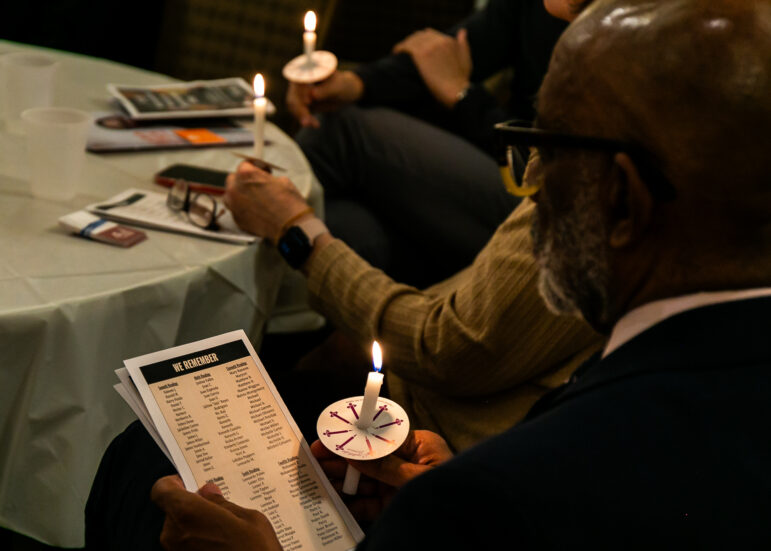

Photo by: Office of the Mayor

The scene of the East Harlen blast immediately after the March explosion. Several businesses derailed by the disaster have yet to receive aid. A new Cuomo administration effort to fill the gap is still ramping up.

As many as 60 small businesses that were damaged in the deadly gas line explosion in East Harlem last March have still not received financial compensation under a program announced in August that aimed to jump-start the aid process.

“I lost more than $100,000 in that single day,” says Domingo Fernandez, owner of the Midtown Fish and Meat Market on East 116th Street. “We had to close the store for 26 days. All of our customers were gone and never came back.”

The East Harlem explosion occurred on March 12 at 9:31 a.m. Two apartment buildings on 116th Street and Park Avenue were completely leveled minutes after residents complained to Con Edison of a gas leak. The NYPD says that eight people were killed. According to the city’s Department of Small Businesses, 60 businesses and nonprofit organizations along 116th and 118th streets in between Madison and Lexington avenues were damaged and forced to close.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced in August that businesses would be allowed to apply for a forgivable $20,000 loan through the East Harlem Small Business Emergency Loan Program. A total of $425,000 was allocated to the program, with funds coming from the state-run Empire State Development Corporation, the Harlem Community Development Corporation, the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone, and private funds raised by Assembly Member Robert Rodriguez.

A month after the governor’s announcement—and nearly six months after the explosion—Fernandez hasn’t seen any of the promised money, and he’s not alone.

Rodriguez’s office attributed the delay to a need to coordinate among agencies.

“This partnership was not easy to assemble, and required time to make sure the program was implemented cohesively,” a statement from the office read.

On August 29, Rodriguez, who represents District 68 in East Harlem, explained in a statement released on his website: “The program will distribute $425,000 in individual loans of up to $20,000 to eligible businesses in order to aid their ongoing recovery from the March explosion.”

Businesses were told they could apply for the loan by contacting the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone.

But Fernandez and several business owners interviewed say their multiple initial phone calls to the agency had not been returned.

The non-government agency says that it has begun the process of returning calls and creating a database for affected businesses since Fernandez placed his initial call.

But business owners say they have only received emails from Joseph Middleton at the Upper Manhattan Economic Zone saying that the agency was still working on the fund and that they would eventually hear from them.

“What has slowed down everything,” Marion Phillips III, the senior vice president for community relations at Empire State development, explained, “is that once the funds were raised and approved, the guidelines for how the funds will be dispersed have to be approved. Then the funds will be transferred to UEZ.”

An aide to Phillips added that the process had not, in fact, slowed down, but was going through standard procedure.

Phillips says that attorneys for the entities that contributed money to the fund are currently reviewing the dispersal guidelines.

On the day of the blast, Fernandez, a 36-year-old Bronx resident who owns the store and manages it with his wife and brother-in-, was shelving cans of beans when, he says, “the sound was literally knocked out of my ears.”

In seconds, the entire front glass facade of the store, which Fernandez owns and manages it with his wife and brother-in-law, was blown out. The store’s refrigeration system lost power and the cans Fernandez was so carefully stacking spilled to the floor.

Next door to Fernandez’ store is Getting Out and Staying Out, a nonprofit organization that aims to reduce recidivism rates amongst the city’s incarcerated males. Mark Goldsmith, president and CEO of Get Out and Stay Out, was in his office the morning of the explosion.

“Our glass windows were basically incinerated,” Goldstein says. “The entire front of our office was gone. We lost hundreds of dollars of computers.”

Goldstein explained that it was not just his accounting books that were affected.

“Our organization is unique in that we take a lot of walk-in guys,” Goldstein says. “We were closed during our busiest months. We had to turn away almost 90 guys. That’s 25 percent of our work. And when you’re a nonprofit that does not deliver results, you lose money from your sponsors.”

Like Fernandez, Goldstein says he has heard little about the loan program. Although he wanted to apply he had not received an application and did not know how to get one.

“In August we were told that we could apply for funding from the city to help recover our losses,” Goldstein says. “But I have not heard from anybody.”

Neither Fernandez nor Goldsmith have applied for other forms of assistance, although the federal Small Business Administration and ConEdison have made funds available.

ConEdison says it gave $52,000 to a total of 22 affected small businesses.

The federal Small Business administration did not return a request for comment, but their aid assistance application for affected small businesses is posted on their website. The application expires on January 8, 2015.

It remains unclear if business owners are fully aware of available assistance options.

The exact number of affected small businesses is also unclear, although the city’s department of small businesses services estimates the number to be around 60.

Rodriguez says that while the program is not yet up and running, it’s not too early for businesses to get in touch: “In the meantime, we welcome and encourage businesses who seek relief to call.”