Photo by: NYC Council

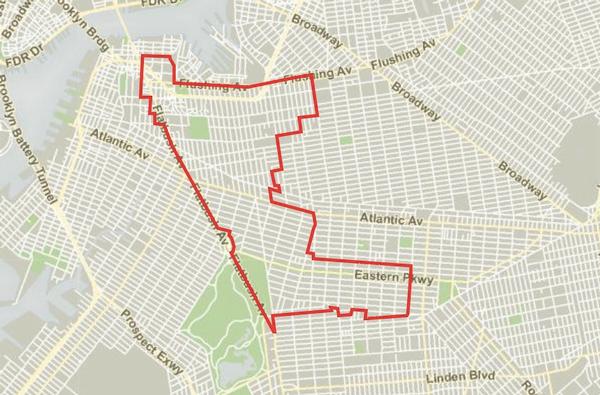

The district touches on Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights but is centered in Fort Greene, Clinton Hill and Prospect Heights, encompassing feverish gentrification and public housing, the Brooklyn Flea and persistent poverty.

When the five candidates hoping to succeed Letitia (Tish) James, the popular 10-year Council Member from Brooklyn’s 35th district, appeared July 19 at the Church of the Open Door in Downtown Brooklyn, the setting hinted at the diverse, contested district.

The church, a modest brick building virtually below the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, is nestled at the perimeter of the New York City Housing Authority’s (NYCHA) Farragut Houses and near a mural warning “Crime Hurts.” Two blocks away, luxury towers have sprouted around Flatbush Avenue, containing few subsidized units despite the boost to developers from a rezoning driven by an overestimated demand for office space.

The district touches on Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights but is centered in Fort Greene, Clinton Hill and Prospect Heights, encompassing feverish gentrification and public housing, the Brooklyn Flea and persistent poverty.

James, now running for public advocate, was a reliable critic of City Hall and notably opposed Forest City Ratner’s Atlantic Yards project and Barclays Center arena, though she didn’t always push back on development (she supported that Downtown Brooklyn rezoning). James has maintained popularity thanks to constituent service, generally populist stances and personal charisma.

Inside the church, the Council hopefuls unsurprisingly vowed they’d preserve funding for public housing, try to spare NYCHA from getting billed for city services like police and seek funding for after-school programs and job training. None embraced NYCHA’s controversial plan to raise funds by allowing mixed-income buildings on underutilized land, though none offered more than partial alternative solutions for the agency’s huge deficits.

Facing a mostly black audience in a historically black district that has gotten whiter and wealthier, the five Democratic candidates, each of them black, presented themselves as agents of resistance, reform, uplift and identification.

“My number one issue is making sure that people that built Brooklyn are able to stay in Brooklyn,” boomed Jelani Mashariki, the most grassroots-centric candidate, a longtime activist who runs a men’s shelter in Bed-Stuy and came to electoral politics via the Occupy movement.

“If you build in Brooklyn, you have to hire from Brooklyn,” proclaimed F. Richard Hurley, an attorney and neophyte pol who regularly reminds audiences he’s married and a grandfather (claims no rival can make).

“I see a community that is overrun by the real-estate industry,” declared Ede Fox, the most policy-oriented candidate, an earnest former aide to two Councilmembers, who regularly cites her work on affordable housing. “It’s important that you have an elected official who has the experience to directly address these issues.”

Laurie Cumbo, founder of the Fort Greene-based Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA), emphasized her hyper-local record, having secured a large grant for after-school programs at public housing nearby. The most polished presenter, Cumbo recalled how she wanted “to be like Lisa Bonet in A Different World and go to Spelman College” and how she later launched MoCADA to recognize that “we have a powerful history.”

Olanike Alabi, a former Council aide, district manager, Assembly candidate and district leader, has the most experience in local politics. She calmly recounted years of small-bore service: fundraising for local schools, an annual food drive, hosting forums on issues like education and stop-and-frisk. Alabi’s opening line—”All honor, all power and all glory to our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ”—hinted at her electoral strategy, which includes endorsements from ministers.

Different pockets of support

As the September 10 Democratic primary, tantamount to election, approaches, the spotlight has increasingly turned to Cumbo, who has the most tangible local record, the most money and the most endorsements, one of which—an unprecedented effort by the real estate industry—presents the highest-profile target to her opponents. (Forest City Ratner, though a member of the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), which helped form the PAC, is not a contributor as of now.)

Cumbo’s raised more than $102,000, with more than $40,000 left before matching funds kick in. Endorsed by the Working Families Party, the United Federation of Teachers and 1199 SEIU, Cumbo has support from Assemblyman Walter Mosley and has hired the Advance Group, the consulting firm that guided Mosley and his political patron, Hakeem Jeffries, the former Assemblyman and now Congressman.

Fox ranks next in fundraising, having reaped more than $81,000, but has spent $69,000. She has support from unions representing transit workers and painters, plus Teamsters Joint Council 16 and several small businesses concentrated in Prospect Heights, where she serves on Community Board 8.

Alabi, who ran unsuccessfully last year against Mosley, has support from District Council 37, the Civil Service Employees Association, CWA Local 1180 and the Correction Officers Benevolent Association. Alabi, who formally entered the race only in May after making sure James wouldn’t seek another term, has raised about $36,000, as has Mashariki.

Both Mashariki and Hurley (who’s raised less than $8,000) have little or no institutional support. They’ve kept their jobs while their rivals campaign full-time.

James has not endorsed anyone; after all, if elected public advocate, she’d have to work with the winner. In another sign the race remains uncertain, neither the Central Labor Council nor TenantsPAC has issued an endorsement.

Other alliances may play a role. Cumbo and Hurley back former Comptroller William Thompson—the choice of the Kings County Democratic Committee—in the mayoral primary, while the other three candidates demur.

Cumbo has support from Progressive Association for Political Action (PAPA), Mosley’s political club. A Mosley press release claimed that the 10,000 signatures for Cumbo and others gathered by PAPA and District Leader Renee Collymore’s Parliament Democratic Club emerged from an “entirely volunteer-driven operation.” Still, Cumbo’s campaign paid Mosley’s mother for community outreach and Collymore’s club for “field mobilization.”

Targeting the ‘front-runner’

“Follow the money,” Mashariki often declares. “My money is coming from the people.” (Well, he lacks institutional money, but his supporters include hip-hop activist Talib Kweli and comedian Chris Rock.) His father Job Mashariki founded Black Veterans for Social Justice, which runs the shelter he heads, and his mother, Bernette Carway-Spruiell, co-founded the Working Families Party’s Central Brooklyn Club.

At the church forum, Fox, hinting at but not naming Cumbo, noted that one rival “has taken thousands of dollars from the real estate industry, including Forest City Ratner,” which, she said firmly, still hasn’t built the affordable housing promised as part of Atlantic Yards. “We must put someone in place who is not tied to any entity.”

Given that Fox’s endorsements include New York Communities for Change—the ACORN successor, which has advocated for Atlantic Yards affordable housing—she can’t claim insulation from political ties. (Fox hired NYCC’s organizing arm to gather signatures to get on the ballot.) But her statement drew applause.

When Cumbo took the microphone, she might have stressed that her campaign had not actually received funding from Forest City, but instead embraced the critique. “My organization, MoCADA, in 2005 received $10,000 from Forest City Ratner to do our educational program,” Cumbo retorted. “It should have been $100,000, it should’ve been $250,000, and every organization, every not-for-profit… should have gotten some community benefit… Our community has received nothing.”

Actually, though Forest City hasn’t met its promises regarding housing and jobs, the developer and partners have made charitable donations to refurbish playgrounds and have regularly distributed tickets to events at the Barclays Center.

“As your City Council member, I’m going to be all up in Forest City Ratner’s face the same way I was to get the $10,000 in the first place,” declared Cumbo. “I’m going to demand that the money comes back. I’m not going to boycott you and say ‘Keep growing, keep getting welfare and we’re going to take nothing of that’.” She easily got as much applause as had Fox.

The dicey issue of how and when to make deals with developers was something with which James, who tried to stop Atlantic Yards, and Jeffries, who secured a yet unfulfilled promise of subsidized condos, wrestled. Given that a tsunami of growth is “going to take place no matter who’s sitting at that table,” Cumbo said voters should choose someone with the “skills to fight, but also to be diplomatic at times.”

Asked at another forum how to address Forest City’s failure to build affordable housing, Hurley said he’d put conditions on Forest City doing more business in the city. Mashariki said we need to “follow who’s getting paid off by Forest City Ratner” and replace them. Alabi suggested accountability had to come from “you,” the people.

“In many ways, the horse has already left the barn,” said Cumbo, suggesting “we have to learn from the mistakes.”

Fox acknowledged that it would be hard to enforce the Community Benefits Agreement, but promised to be a nagging “attack dog.”

Double-edged support

“The first thing I built in my community has not been my campaign,” Cumbo likes to say. Her narrative resonates not only with locals who admire the museum but also a range of arts and cultural contributors to her campaign, from artist Danny Simmons to Leslie Schultz of the arts presenter BRIC.

But rivals mutter that Cumbo overplays her ties to “my community,” since she moved to the district only in June. The Brooklyn-born Cumbo says she’d hoped her longtime East Flatbush address would have been redistricted into the 35th.

At forums, she has claimed, though she departed MoCADA in January, that “I am a small business owner.” “We now have 50 employees, whether they are full-time, part-time, independent contractors, or vendors,” she said at one forum, though her website states she “successfully manages… eight staff members.”

Though several candidates have received large sums from unions and other allies; Cumbo’s the only one to get a big real-estate contribution; she got $2,000 from Stephen Green, chairman of S.L. Green, the city’s largest office landlord.

Cumbo’s most controversial support, however, has come from Jobs for New York, the PAC that involves construction-related unions but is funded by the real-estate industry, an unprecedented outside influence in Council races.

As Prospect Heights resident Gib Veconi—active in the Prospect Heights Neighborhood Development Council and Atlantic Yards Watch, and a Fox contributor—wrote July 29 on Prospect Heights Patch, he received direct mail touting Cumbo for four straight days from Jobs for New York.

Cumbo, noted Veconi, had previously pledged not to accept aid from the PAC, but had yet to publicly reject the endorsement. The next day, more than a week after the mailings had begun, Cumbo issued a statement, “Setting the Record Straight,” noting that she hadn’t had contact with Jobs for New York, and believed its plan “erodes the goals and principles” of the campaign finance system.

Cumbo “respectfully asked” Jobs for New York—which cannot formally communicate with candidates—to stop spending on her behalf, but thanked the PAC “for its excitement and belief in this campaign and I look forward to working with its various constituencies as your next City Council Member.” Fox soon slammed “my opponent’s disingenuous attempt to distance herself… while at the same time thanking them.” Alabi also criticized “special interests.”

Cumbo then issued a press statement moderating her thanks to “I appreciate their belief in my campaign,” with no mention of the “various constituencies.”

One of those Jobs for New York constituencies, United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1500, has in fact endorsed Fox.

Fox, who grew up on Manhattan, was the first black female student body president at the University of Michigan, and pursued a Ph.D. in anthropology before going to work for a union, has lived in the district a decade. She’s cast herself as the candidate most prepared for the office, having served as budget director for Council Member Melissa Mark-Viverito (who’s endorsed her) and then as Chief of Staff for Jumaane Williams (who hasn’t), with a “real vision” for economic development, involving rezonings and manufacturing jobs.

“I actually have experience creating over 1,000 units of affordable housing around the city,” Fox states on her website, and stresses in forums they’d be targeted toward lower-income residents. In an interview, she acknowledged that some of the projects—in East Harlem, the Upper West Side and South Bronx—are still in process.

Her role chairing the Environment/Sanitation Committee of Brooklyn Community Board 8, Fox says, has shown her the nitty-gritty of local life. (The 35th district also includes a large chunk of CB 2, as well as pieces of CBs 3 and 9). She’s stressed the need to simplify city codes so local businesses “aren’t constantly fined and penalized.”

Fox’s fundraising includes support from Prospect Heights—she co-founded Prospect Heights Democrats for Reform—and a good sprinkling of people working in government, including contributions from two aides to James, Aja Davis and Simone Hawkins.

Beyond the development debate

If the candidates sound progressive on many issues—there’s little disagreement about charter schools, or stop-and-frisk—on others they step more gingerly. As Streetsblog reported after a forum on transportation issues, four candidates supported expanding the Citi Bike program but only if no on-street parking were removed, while Hurley opposed expansion. (He backed off after being chastised on Facebook.)

Alabi, Fox and Cumbo, when asked if they supported reduction or elimination of parking requirements—which adds to the cost of a building and presumably is less necessary in a district with robust transit—all responded cautiously. The latter two wouldn’t support congestion pricing.

Such caution may reflect larger tensions. Cumbo, whose museum has aired issues of racial identity, police violence and gentrification in exhibits and discussions, later observed, when asked what she’s learned while campaigning, that she’s heard coded language and indirect gripes: black residents fear that new restaurants and bike lanes are there to serve wealthier white newcomers, while white residents express dismay about boisterous (unmentioned: black) teens hanging out or the lack of “good” schools.

“First, it has to be spoken about,” Cumbo said. “We’ve got to be real that we’re living in a diverse community.”

The candidates diverge when asked what they’d like to get done first legislatively. Mashariki urged an integrated approach to social services and direct election of Community Board members.

A member of FUREE (Families United for Racial and Economic Equality), Mashariki, steeped in hip-hop, has led anti-gang, anti-violence workshops in Latin America via the Global Block Foundation. He cited cuts in the city’s Work Advantage housing subsidy program as turning him toward legislative issues, then got a jump start with Occupy Wall Street and later Occupy Sandy

Mashariki envisions dramatic devolution: participatory budgeting, “people’s assemblies” to gauge community priorities and “skill-sharing” to democratize learning. His 14th “bold, progressive idea”—on top of the 13 already promoted by the Council’s Progressive Caucus—is to offer psychological support to those touched by crime, such as witnesses: “You can’t have progressive ideas if the people are walking around scarred.”

Alabi‘s priority would be to raise the living and prevailing wages. And though she’s hardly conservative, the church-infused Alabi is willing to criticize NYCHA but also warn, “It’s not NYCHA that’s using our elevators as bathrooms [or] engaging in some of the activities we see in the stairwells.” Alabi can be cautious on the stump—at one forum, she allowed that Community Board appointments might be term-limited, but didn’t take a position.

Cumbo stresses budget equity, saying that funding fairly distributed among the Council districts would diminish poverty. On her website and at forums, she also promotes cultural tourism, which she suggests would yield “thousands of meaningful jobs,” given the growth of the BAM Cultural District. She also cites her role launching Soul of Brooklyn, a network aimed to promote (and distribute grants to) black-oriented nonprofit organizations and businesses.

Fox prioritizes rezonings within the district to meld affordable housing, market-rate housing and light manufacturing, along with a local-hiring requirement for projects using city money.

Hurley cites his “hire in Brooklyn” catchphrase, which plays well, though he doesn’t have a plan to implement it. He says he’d pay more attention to Crown Heights.

Down the stretch

Hurley calls himself the “broke-est candidate” in the race, and says he’s running to win, but campaign literature that points to his law firm’s web site doesn’t dispel murmurs that he may have another agenda.

The other candidates, thanks to 6-to-1 matching funds (for contributions from New York City residents up to $175) likely will be able to promote themselves significantly. Will Jobs for New York continue to promote Cumbo? The organization didn’t respond to queries.

A five-way race in which each candidate has pockets of strength could yield victory with a weak plurality. As Primary Day approaches, campaigning should get more intense, as newspaper endorsements emerge, mailers circulate and candidates’ surrogates step up their ground game.

Ordinary people, suggests Mashariki, “want someone who’s not connected to the political power structure.” If so, it’s not clear that voters in the 35th will get what they want.

One thought on “Real-Estate Lobby Dives into Central Brooklyn Council Race”

Pingback: Forest City Dog Training Club Rockford | Your Best Dog Food