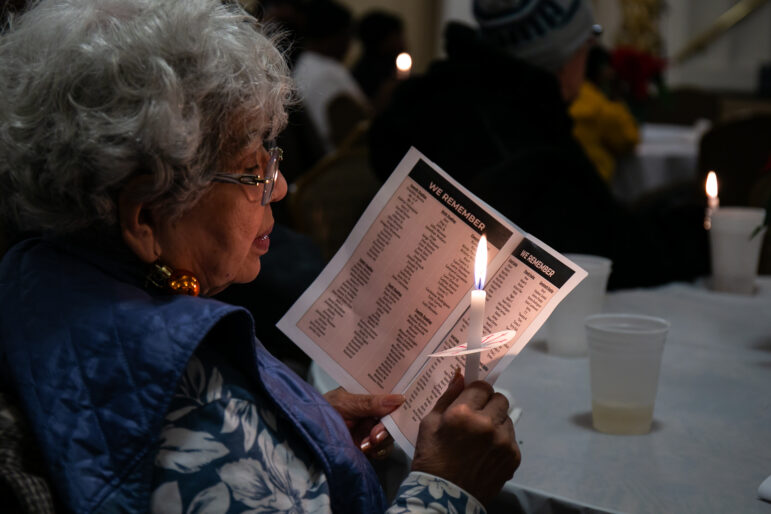

Photo by: Marc Fader

The St. Nicholas Houses are the only place Henrietta Bishop has ever called home. But amid concerns about repairs and security, she’s contemplating leaving.

For Henrietta Bishop, 58, St. Nicholas Houses—a sprawling public housing development (pop. 3,000) comprised of more than a dozen 14-story buildings in central Harlem—is the only place that she’s ever called home. A smile crosses her face as she recalls attending concerts at the nearby Apollo Theater during the early 1970s (“You really got a complete show,” she says). And she’s equally jovial as her thoughts turn to fellow longtime tenants, including a woman in her 80s who Bishop calls her “spiritual mother.” But these days, Bishop’s sunny disposition is being put to the test by long-running woes at “St. Nick.”

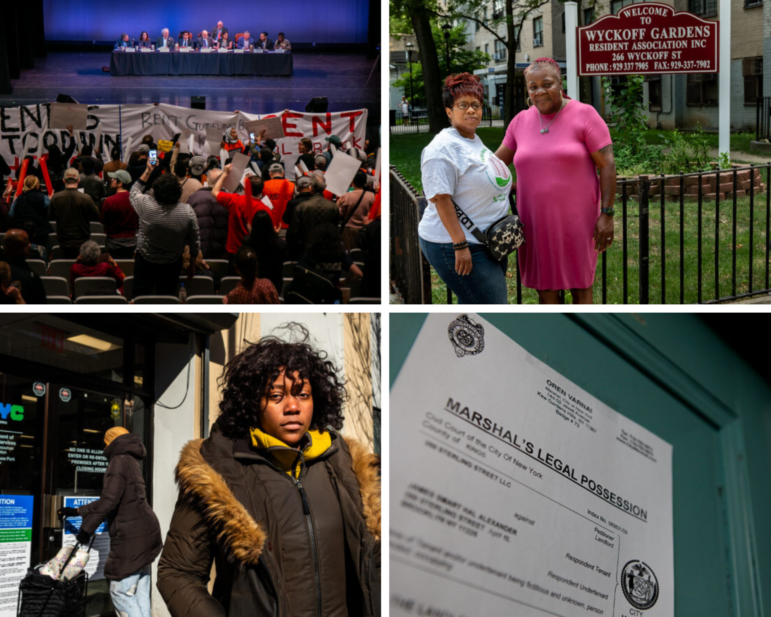

At first glance, St. Nick’s maladies are fully visible inside Bishop’s 10th floor two-bedroom apartment, which she’s currently sharing with her daughter and a granddaughter. The drab living room walls sorely need a fresh coat of paint. Elsewhere, the scruffy and discolored flooring is beginning to show evidence of wear and tear. Yet for Bishop, both are relatively minor annoyances compared to more pressing concerns. Earlier this summer, she found herself stuck for nearly an hour inside one of the building’s hazard-prone elevators. And because the building’s intercom system is inoperable, the main entrance door is unlocked. “Sometimes when I get home late from work, I see somebody standing by the door,” she says. “Should I go in? I’m a little skeptical because I don’t always know who’s who.”

After a Daily News series probed the New York City Housing Authority’s spending practices—from the six-figure salaries of several board members to $42 million in unspent City Council funds earmarked since 2004 for the installation of security cameras at several housing developments — a broad coalition of elected officials, policymakers, and housing advocates demanded widespread changes to the nation’s largest public housing system. NYCHA Chairman John Rhea, who was appointed by the mayor in 2009, announced in early August that NYCHA would support future state legislation overhauling its board. With the exception of its chairman, the remaining seats in the proposed five-member panel would be unsalaried. Additionally, the board would reserve two seats for NYCHA residents.

But advocates for NYCHA tenants are pushing for different reforms—ones that give public housing residents more power to challenge an authority that, as it fights for survival, is considering significant changes to what public housing means in New York.

More than money

Last year, Community Voices Heard, a grassroots group in Harlem that advocates for affordable housing, published a poll of more than 1,400 residents at 71 public housing developments citywide. In 10 out of 26 categories, ranging from maintenance and repairs to management, NYCHA received a failing grade.

Bishop, for one, wonders if NYCHA worsened delays by adding another layer of bureaucracy with its Centralized Calling Center system, which was adopted in 2005 to field requests for repairs. “Now you’ve got to call a number and they give you a ticket number to make an appointment,” she says. “So my apartment is about to flood and you’re talking about a ticket number? It doesn’t make any sense. I wish I understood what they’re doing.”

Many of NYCHA’s detractors concede that the agency faces a daunting task in serving roughly 400,000 low-income New Yorkers who live in subsidized housing. With a sizable stock of aging buildings dating back to the 1940s and ’50s, the cost for maintaining those properties has risen sharply in recent years. Meanwhile, the number of struggling families on the waiting list for public housing apartments and Section 8 rental assistance continues to swell. And it’s happening at a time when federal spending on public housing nationwide has been decreasing. NYCHA, for instance, estimates that Congress has reduced funding for its operations by $23 million in the current fiscal cycle when compared to last year.

“Public housing isn’t popular in Congress and generally gets short shrift. The funding that it receives will be even lower in the forthcoming year because of the deficit reduction agreement that was reached in Washington and the budget cuts that will be coming to domestic programs,” explains Victor Bach, senior housing policy analyst at the Community Service Society of New York (CSS)—a research and advocacy group (and parent company of City Limits). “Obviously NYCHA can’t survive as it is.”

Nor is the political environment for NYCHA getting any friendlier. Brooklyn Assemblyman Hakeem Jeffries has called for a congressional investigation of NYCHA. Meanwhile, Republican Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa has launched a probe into the circumstances surrounding the hiring of Boston Consulting Group (BCG) to analyze NYCHA operations. BCG was selected to conduct the study through a no-bid contract. As City Limits first reported last fall, BCG formerly employed Rhea, though the connection was not mentioned on Rhea’s official biography.

But public housing residents have a different set of concerns than the BCG deal—some of them related to steps NYCHA is contemplating in response to its fiscal crisis.

In early August, for instance, dozens of tenants protested outside of the authority’s Manhattan headquarters. The demonstrators called for greater transparency about the role that private developers are slated to have at some properties and the potential impact of Moving to Work (MTW), a program that allows public housing authorities to waive some federal regulations to determine the best use for HUD’s funds based on local needs.

Freedom, fears

MTW dates back to the mid-1990s, a period when federal policy mandated deregulation in multiple sectors, resulting in everything from widespread changes in the broadcasting industry to welfare reform. Facing pressure to cut costs, HUD crafted MTW as a concession to appeals from local public housing agencies to be granted more authority. MTW was also designed in response to the growing demand among some observers that government agencies should do more to help individuals transition away from dependence on public assistance.

Generally, public housing agencies are supported by HUD through three distinct and highly-regulated sources—Section 8 housing vouchers, public housing funds, and capital for public housing operations. MTW gives housing authorities the flexibility to combine those funds to pay for anything from infrastructure projects to measures that promote more efficiency by the agency itself or self-reliance among residents.

Nationwide, MTW—which is presently operating in more than 30 jurisdictions across the country—takes many forms. In Oakland, for instance, the local authority uses MTW funds in a family reunification initiative that houses formerly incarcerated women with their children. Elsewhere, Chicago—whose housing authority outsourced the management of developments to private firms—is using its MTW dollars to rehabilitate some 25,000 units of housing. And the Philadelphia Housing Authority is running a Family Self-Sufficiency office that connects residents with employment training programs.

NYCHA envisions that it can use MTW to invest more funding from HUD to rehabilitate buildings and individual units.

But some fear that loosening the arrangement between HUD and NYCHA would allow the authority to adopt a range of measures that could negatively impact tenants. “There’s a lot of concern about Moving to Work,” says Valery Jean, executive director of Families United for Racial and Economic Equality (FUREE)—a Brooklyn nonprofit group that provide support to women of color in public housing. “There could be a day when NYCHA sets time limits for families or require that residents perform community service as part of their stay.”

NYCHA insists that long-standing provisions that protect low-income tenants—such as the federal Brooke Amendment that limits rent to 30 percent of income—will remain intact. But a position paper by a coalition of advocacy and resident groups called the NYC Alliance to Preserve Public Housing argues, “Despite the best of current NYCHA intentions, it offers no guarantees for the future,” and proposes that the authority sign a memorandum of understanding outlining the parameters of MTW in New York.

Meanwhile, NYCHA is also showing interest in another federal measure known as the Rental Assistance Demonstration. The pilot program would allow the authority to collaborate with private developers to establish mixed-income housing. In a trial run, NYCHA is limited to doing so at 4,000 units, whose location has yet to be identified. The Alliance to Preserve Public Housing, recently submitted a letter to NYCHA that calls for a special hearing on the program to examine its potential consequences.

Additionally, NYCHA’s plan for the next fiscal year includes the sale of land parcels at some properties, including Boston Secor Houses in the Bronx and Linden Houses in Brooklyn, to private developers. Brooklyn City Councilman Charles Barron—whose district spans from parts of East Flatbush to East New York and includes 11 public housing developments—is closely watching those deals. “If you’re going to sell NYCHA land to build youth centers and things that are beneficial to NYCHA residents, that’s fine,” he says. “But if it’s sold to some developer to build luxury housing or something unrelated to NYCHA residents, then there’s definitely a problem.”

Aim to improve tenant advocacy

Amid those proposals that could produce systemic change to public housing, housing activists complain that a large segment of the resident population is mostly oblivious to its potential impact. “When NYCHA says ‘Yeah, we met with 1,000 tenants,’ we still find a lot of confusion,” Jean says, referring to a recent series of assemblies that were held citywide to update residents on NYCHA’s pending plans. “We mentioned Moving to Work to some of the people who attended and they thought it was a program about jobs.”

Many advocates are now pushing for tenant associations to be supplied with counsel from independent experts on public housing policy to ensure that they’re adequately informed to play a decisive role in the decision-making process—as federal law requires.

There are some 240 active public housing tenant associations. Tenant association presidents, representing nine separate districts across the five boroughs, are elected to lead an alliance known as the Citywide Council of Presidents (CCOP). The group as well as another tenant bloc, the Resident Advisory Board, is responsible for making suggestions on policy and voicing residents’ concerns to NYCHA. Federal guidelines stipulate that HUD provide financial support to resident associations through tenant participation funds, which covers everything from newsletters to conferences.

But the funds, which are distributed through NYCHA and total nearly $4 million annually, has been a major point of discord due to its incomplete distribution. Earlier this year, NYCHA disclosed at a Council hearing that some $15 million of those funds remain unused. Some activists are pushing for a portion to be set-aside for tenant groups to secure experts of their own who can advise them on NYCHA’s proposals and policy changes.

It’s a plan that Madelyn Innocent, a longtime resident at the Frederick Douglass Houses on the Upper West Side who formerly co-chaired the development’s Grievances Committee, fully endorses. These days, she’s counseling residents who are in the midst of one of the most contentious issues currently unfolding at many developments citywide—downsizing. It’s a dilemma that strikes at the core of a long-debated question—namely, does public housing represent temporary assistance during times of financial hardship or a boundless safety net in a city where affordable housing is increasingly scarce?

In recent months, some longtime NYCHA tenants—who are mostly elderly—residing in multi-room apartments have received vacate notices. With available space at a premium in many developments, tenants who once shared apartments in households that have grown smaller—or “downsized” in recent years—are being told to move into smaller NYCHA units to accommodate families on the waiting list. But in decades-old properties that were originally geared for large households, studios and one-bedroom apartments are few and far between. As a result, some longtime residents are being offered single NYCHA units wherever they’re available, including in other neighborhoods. “Where are these people going?” asks Innocent. “A lot of the tenants here are willing to switch to other apartments in the same development, but for reasons I don’t know—management doesn’t seem to like that idea.”

But NYCHA faces no easy answer with more than 161,000 people on the public housing waiting list and some 55,000 tenants who are residing in apartments that are more suitable for larger households, according to the agency’s latest figures.

In the meantime, the authority is encouraging tenants who have received vacate notices to join a transfer list as it develops a long-term strategy. “NYCHA does not seek to remove families from their neighborhoods and communities and away from families, neighbors and support systems,” the authority explains in a statement to City Limits. “Under-occupied families who are requested to move, regardless of age, are given almost unlimited choices of destination locations. They may select to remain either within their current development or move to almost any other development within the NYCHA system.”

Still, a sizable number of those cases will present hard choices. “There are a lot of people in the wrong apartments, but what NYCHA isn’t saying is that there just aren’t enough small apartments available,” says Judith Goldiner, an attorney-in-charge at the Legal Aid Society’s Civil Reform Unit whose clients include NYCHA residents facing downsizing. “It’s hard to generalize because each case is different. If the individual tenant is extremely elderly, we try to get a waiver. If someone is disabled, we try to ensure that they get an apartment with extra room for their medical equipment. It all depends on what the situation is.”

A hand in budgeting?

For Innocent, 55, the downsizing issue underscores a profound lack of clout among the tenants. “We’re fighting over something that can be resolved if we got together and worked it out,” she explains. “You can’t dismiss the residents. If NYCHA keeps trying to make decisions for everybody with very little input, then how can you reach a consensus?” It’s a point that has led many housing activists to support an initiative that they believe could, in part, empower tenants like never before—participatory budgeting.

Participatory budgeting first gained international attention when it emerged from the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre during the late 1980s. After a series of meetings, local citizens voted on a range of projects including road work and sewage treatment.

Last year, a participatory-budgeting process directed some New York City funding. In four City Council districts, area residents convened public meetings to decide how to spend millions of dollars in capital funds for neighborhood improvement projects. The program sparked a flurry of ventures, ranging from repair work at the Prospect Expressway to technology upgrades at three public schools in south Queens. The idea is slated to be enacted in four additional Council districts this fall.

It was the Participatory Budget Network, a nonprofit group in Brooklyn, in tandem with Community Voices Heard (CVH), that introduced the initiative in which residents vote on capital improvement projects to New York. Earlier this year, CVH proposed bringing participatory budgeting to city’s public housing residents.

“Can you imagine what participatory budgeting can do for us?” asks Innocent. “Look at some of the people who came out of public housing like Whoopi Goldberg and Jay-Z. We should be reaching out to see if we can do something together to help make public housing better.”

Under the plan, tenants would hold meetings with NYCHA staff, elected officials, labor unions, and civic groups to receive crash-courses on the inner-workings of policymaking and municipal budgeting. Also during those sessions, a slate of tenant budget delegates would be selected and critical needs at various developments would be identified among the tenants themselves. After the projects are assessed and the cost estimates are produced, the budget delegates would convene general assemblies in which the projects are put to a vote. The issues with the highest percentage of the vote would then be financed using budget funds. CVH recommends launching the effort in one NYCHA district in a trial run before expanding further.

Some wonder whether, given the distinct differences between the political system of New York and Porto Alegre, participatory budgeting can draw enough participants to make the process legitimate. While some 6,000 New Yorkers reportedly took part in the final vote for community development projects under last year’s pilot program in a handful of City Council districts, the amount of participants in Porto Alegre grew exponentially from nearly 1,000 citizens in 1990 to 40,000 about a decade later partially due to the aggressive organizing efforts of a national socialist party.

NYCHA was apparently slated to hold further meetings with CVH about the proposal, but those plans are still pending in the aftermath of the authority’s spending controversy.

Ahead to 2013

As NYCHA battles to repair its public image, some observers cautiously believe that a favorable climate for reform is emerging. After recently declaring support for future legislation revamping NYCHA’s board, Rhea announced that he filled a long-vacant post with the hiring of a general manager. Yet the selection of Cecil House, a veteran public utilities executive, is already being greeted with cynicism in some quarters given his lack of housing experience.

And with so much of NYCHA’s future course and direction still to be determined, as the final year of the Bloomberg administration draws near, some housing advocates are vowing to press for reform elsewhere. “We’re planning to make public housing an issue in next year’s mayoral campaign,” says Bach of CSS. “We definitely plan to see where the candidates stand.”

At least one mayoral hopeful—Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer—has weighed in with a plan for reconfiguring NYCHA’s board. The proposal recommended that NYCHA expand to seven panelists of diverse professional backgrounds, most of whom would receive stipends as opposed to full salaries. NYCHA has indicated that it backs some elements of the plan—notably, the inclusion of an extra tenant. It was only last year when a NYCHA resident became a board member for the first time in the agency’s 75-year history.

The report from Stringer also supports a key tenant demand with the recommendation that NYCHA help to set up an independent advisory group for tenants on technical matters, ranging from zoning rules to land use. Still, some critics are skeptical as to whether NYCHA residents will actually play a significant role on a newly-revamped board. “Naming one or two tenants is just an attempt to placate the public,” argues Barron. “The whole management structure needs to change so that the people who are most affected are occupying positions of power.”

For its part, NYCHA says that tenants are regularly kept abreast of existing policies and pending plans. The release of the agency’s outline of current and pending priorities was accompanied by a series of roundtable discussions across the city and a public hearing in midtown Manhattan in late July. “In the past 18 months, NYCHA has stepped up resident engagement by meeting directly with our customers in community meetings, attended by thousands of residents, to discuss the challenges of maintaining public housing,” Sheila Stainback, a NYCHA spokeswoman, tells City Limits. “Providing positive experiences for this vast audience across all of these locations and interactions is a major challenge. And we have made it one of our top priorities to raise customer service to excellent standards.”

For some observers, the response to the NYCHA controversy could serve as a referendum on the city’s subsidized housing policy. “We can actually see what the current sentiment toward public housing is. Unfortunately, when you step away from the scandal part of it and think about what’s happening nationally—there’s definitely the sentiment that the federal government shouldn’t be funding public housing at all,” says Jean of FUREE, who cites the recent demolition of public housing developments in cities including Atlanta, Chicago and New Orleans.

But the authority’s desperate state only increases the need for tenants to hold NYCHA accountable, Jean says. “We’re actually reviewing legal options to see whether all of these proposals we’re hearing about should be happening without input from the residents,” she argues. “We’re definitely not going to fall for any kind of spin that public housing is so decrepit and bad that it needs to be privatized or even state-controlled. Yes, the NYCHA board needs to be overhauled, but the solution needs to be collaborative.”

On W. 129th St., construction crews are busily working to erect a $100 million Harlem Children’s Zone charter school and community center. Longtime St. Nick resident Henrietta Bishop can easily view the proceedings from her apartment. Like many who initially opposed the project—which has received partial funding from Goldman Sachs and Google—Bishop isn’t sure what the future holds.

She fondly remembers a time, decades earlier, when a mercurial custodian dubbed “The Gray Ghost” patrolled the grounds of St. Nick to ensure that local children stayed out of trouble and away from the grass. “When you got to the elevator, it was always ‘Hello Mr. and Mrs. So-and-So.’ It was like a community because everybody knew everybody,” she says. Yet she also recalls an era when nearby Eighth Avenue was consumed by the heroin epidemic of the 1970s. Plagued by heavy drug trafficking, her building earned a notorious nickname on the streets—”Little Vietnam.” These days, it’s random gun violence that concerns many residents. In June, one man was killed and three others were wounded when gunfire erupted during a pickup basketball game at St. Nick.

After experiencing St. Nick’s many periods of transition over the years, Bishop sometimes finds herself contemplating a prospect that once appeared unthinkable—leaving after retirement. “I’m giving myself five more years,” she says. “And then, we’ll see.”