Photo by: NY governor’s office

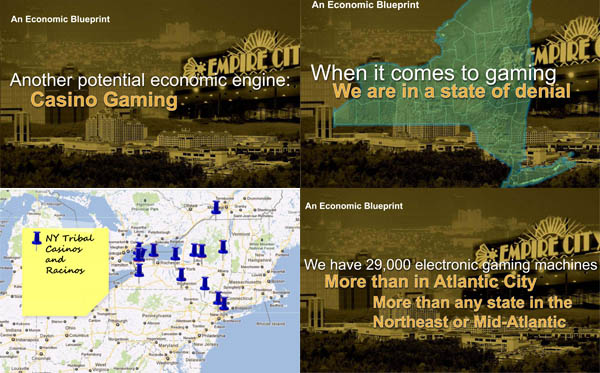

Gov. Cuomo’s budget briefing made the case for full-fledged casinos in the Empire State, in part by suggesting that the line between casino gambling and other forms of gambling already legal in New York is an artificial one.

Slot machine players come out in the thousands to Genting’s Resorts World New York casino at the Aqueduct racetrack every day. Individually, they each square off against one of thousands of gaming machines, each row sporting different names such as 50 Lions, Carnival of Mystery and Wall Street Winners, although the continual button-pressing game play is common among them all. Most players tap their buttons without expression, hoping to hit the jackpot with each spin. They’re locked in a fight against the odds and, of course, on a normal day, most of them will not come out winners.

Indeed, thus far, the new racino seems wildly profitable, so much so that Gov. Cuomo sees it as just the beginning of the development of new gambling and entertainment opportunities at Aqueduct.

In other areas of the country where full-scale gambling has been considered, a battle has broken out over benefits versus cost. If that same fight is taken up here, attention is likely to focus less on whether social costs of gambling exist than whether the positive financial impact of gambling outweighs those social concerns.

And in that contest, casino opponents may face prospects no better than the average gambler who visits the quasi-casino that already exists in Queens.

Revenues high and growing

The benefits of gambling to New York are obvious and easy to quantify. All the numbers and statistics making headlines at the moment point to the Racino being a boon for all New Yorkers. Despite not opening until the tail end of October, the Aqueduct Racino brought in $90 million in revenues for the state in 2011, most of which went toward education. And according to Stefan Friedman, managing director at consulting firm SKDKnickerbocker, which represents Genting, the revenues are expected to remain impressive even after the Racino’s “novelty factor” wears off; Genting expects to bring in $300 million to $400 million for the state each year, not including the profits they’ll keep for themselves.

Perhaps even more powerful are the estimates of what New York is missing by restricting what its gaming facilities can offer. Friedman says $3 billion to $5 billion in entertainment spending leaves New York each year, bound for full casinos (which unlike Racinos have live dealers and table games) elsewhere.

“Gaming is here,” he says. “There are dollars going out of state right now, and look, we love our friends in New Jersey and Connecticut, but we don’t love them that much to be giving away revenues to them at a time when frankly, every year, there are budget deficits. Every year, we’ve been seeing stagnant employment.”

So it’s no wonder Cuomo, at the helm of a state that’s still very strapped for cash, has hopped on the casino bandwagon: It looks like free money for the state that doesn’t involve raising taxes, it creates lucrative business for the private sector and, maybe the most important concern in this economy, it appears to be a great source for job creation. Still, some say there is more to the picture.

“Typically, [upon the opening of a new casino] the economic studies find a boost in local revenues as well as business, an increase in a number of jobs and a bunch of things like that. The other side of the coin is harder to measure,” says David Just, associate professor of economics at Cornell, referring to the social costs that often accompany casinos. “That’s why it’s really hard to argue against these things.”

Tall order for opponents

The success of Aqueduct and the estimates of foregone revenue mean anti-gambling groups such as the Coalition Against Gambling New York (CAGNY) and Stop Predatory Gambling face some major hurdles in convincing the public that casinos are not worth the social costs.

“Over the long-term, no one wins in a casino,” says Charlotte Wellins of CAGNY. “Our government is pushing an addictive product, pure and simple… What if our government started pushing drugs like they’re pushing gambling? You know, if they were going to push prostitution, that would bring in revenue too. But will it improve the quality of life of our citizens?”

Beyond the moral concerns raised by gambling, Wellins argues that the job creation and perceived economic benefits of running casinos are overblown.

“Many casinos, if you look at Atlantic City, many of them hire part-time employees so they don’t have to pay benefits to them,” she said. “They’re low-paying jobs to begin with and they produce nothing. How can that help our economy? There’s nothing produced in a casino.”

Dan Hajdo of Casino-Free Philadelphia also speaks strongly against the supposed benefits that are meant to come from opening casinos, saying the “social costs, in economic terms, outweigh any political revenue.”

Hajdo points to a number of reports and studies that document the addictive nature of casino gambling and the ruinous effects it has on the lives of addicted gamblers and their loved ones. One of these is the 2007 Pennsylvania Intergovernmental Co-operative Authority Staff Report, which estimates the yearly social costs per pathological gambler ranges from $15,000 to $33,500. According to Just, the prevalence of pathological gambling increases among locals when a casino opens up.

Before a casino opens, Just says, a person who has lost a job or suffered some other blow might need a few days to regain their bearings and then go out and start looking for work or looking for some way to solve the problem. A casino can interfere with that cooling-off period, Just says. “What tends to happen when you have the casinos right down the street is, in that period when you’re trying to get your head together, you’re out gambling because you see that as a way out; you see that as a way to quickly make back this money that you lost. Bankruptcy rates increase noticeably – something along the lines of 6 percent.”

Impact on the poor

The 1999 National Gambling Impact Study Commission found that compulsive gambling rates double in areas within 50 miles of a gambling facility.

But accepted forms of state-sponsored gambling in New York, like lottery jackpots and scratch-off tickets, can also eventually lead to gambling addiction. What’s more, those games—more than casino gambling—disproportionately attract low-income people.

Contrary to one anti-casino myth, the majority of casino gamblers are not poor—that would be a risky revenue model for gaming companies—but low-income people are more likely to gamble than more affluent Americans.

Both opponents and proponents of gambling find support in the research. Wellins points to Baylor economics professor Earl Grinols, a former senior economic adviser to President Ronald Reagan, who finds that gambling costs outweigh benefits by a harsh measure of three to one, when factoring in the societal costs brought on by pathological gamblers along with other issues.

Friedman points to the work of Harvard Professor Howard Shaffer, who has time and again found that the rate of pathological gambling has remained steady despite the expansion of gambling in the United States over the past 35 years. (Shaffer, however, came under fire in 2008 when it was revealed that his institute had been funded with $9.1 million in casino industry money since 1996. “It is possible to do good research independent of the funding,” he said in a Bloomberg story at the time.)

Aqueduct competition supports plan

Friedman reports that now that the casino is past its first few months of opening, attendance has calmed to the traffic initially expected – still a strong 20,000 to 25,000 people a day.

He is particularly happy to note that the clientele has become more varied in recent weeks, moving away from the local surge that dominated the first couple months and toward drawing people in from New Jersey, Connecticut, other parts of the northeast and from travelers doing an extended layover at JFK Airport. The number of gaming machines has doubled in the casino since its opening, from 2,500 to 5,000.

Under the casino plan, additions to the Resorts World New York casino would include table games with live dealers. Beyond the casino proposal is a plan to build a 3.8 million-square-foot convention center on the same site offering restaurants, Broadway shows and other non-gambling attractions. The estimated $4 billion project would be paid for by Genting, a fact that Cuomo has stressed to New Yorkers whenever the issue has arisen.

However, table games cannot be added at Aqueduct until legislators pass a constitutional amendment, something Genting and other pro-gambling organizations hope to drive through state government as quickly as possible. At the earliest, it would be November 2013 before the amendment could be approved or denied by voters.

The clamor for live table games is not unique to the Aqueduct racino. A little over 20 miles north at the Empire City Casino at Yonkers Raceway, owners are happy to see Cuomo encouraging the implementation of table games along with other expansion at Aqueduct.

Taryn Duffy, director of public affairs at the Empire City Casino, reports that Empire City experienced 10 percent growth in terms of revenue each year since opening in October 2006, although last year’s growth was a more modest 2 percent, probably thanks to competition from the new racino at Aqueduct. Still, Empire City feared getting much worse of a hit than they did, according to Duffy.

“That really just kind of proves what we’ve believed all along,” she says. “Which is that we’ve not scratched the surface in terms of [gaming] awareness here in New York. The market’s certainly not been saturated, [it hasn’t] even been dented.” Rather than drawing extensively from Empire City’s market, Duffy believes Aqueduct has, for the most part, tapped into a previously undiscovered gambling population in Queens and the surrounding area. And Genting’s new plan doesn’t bother her either because, Duffy says, Empire City expects to benefit from the easing of New York’s gaming laws as much as Aqueduct does.

For the record, the nine racetrack casinos in the state did well last year, all experiencing revenue increases. Overall, they hauled in $1.26 billion, a 15.8 percent increase from 2010, although that percentage was helped considerably by the opening of the Aqueduct racino, which outpaced five out of the other eight racinos in just two months of existence. The racinos keep roughly 30 percent of their revenue;14.5 percent goes toward horse racing, 10 percent goes toward the state lottery and, as mentioned before, 44 percent goes to education, according to Friedman.

Nightlife impact gauged

The convention center proposal is separate from the push for a full casino. Genting is hoping to have Phase I of the convention center opened by the end of 2014, if the project can overcome what polls suggest is stiff public opposition that Friedman attributes to a misconception that taxpayers will fund the center’s construction. (“There is no public financing in this,” he points out.).

Friedman mentioned that the center would create 10,000 construction jobs, 10,000 permanent jobs and thousands more “spillover jobs” in areas such as food service, hotels and entertainment. He was not able to make an estimate on how many jobs would be created by the establishment of full legalized gambling at Aqueduct, but he said the racino currently employs 1,500 permanent workers, all of whom are offered benefits.

But for all casinos might add to an economy, some gaming facilities also take away. “Casinos create what economists call a ‘substitution effect,'” Hajdo, the Philadelphia anti-casino activist, says. “Money spent at the casino is money that is not being spent at other businesses. That is why local business in Atlantic City was decimated as casinos were built. For every person hired by a casino, the casino can cost up to three jobs elsewhere in the community.”

Hajdo’s reference is to the 40 percent decrease in the number of restaurants in Atlantic City in the decade following the arrival of casinos, as reported by the National Coalition Against Legalized Gambling. Another example comes from the Family Foundation, which found that 97 percent of businesses in Aurora, Illinois experienced a decline in revenue after the arrival of the Hollywood Casino in 1993.

But few are expressing fear of a substitution effect in New York.

Andrew Rigie, Executive Vice President of the New York City office of the New York State Restaurant Association, viewed the convention center as “a unique new venue for the restaurant industry,” saying it would provide new jobs and exciting new dining options.

Paul Seres, president of the New York Nightlife Association, also said he wasn’t concerned with the well-being of the existing entertainment-based economy in New York, saying the casino and convention center would provide a new draw for tourists.

Finally, Smith College Economics Professor Andrew Zimbalist said professional sports attendance would likely remain unaffected by the new and ongoing developments at Aqueduct.

When it comes to the cross-state battle over casino revenues—Massachusetts, for example, is preparing to approve casinos in each section of the state—Friedman wrote off the issue, saying full legalized gambling would have to get the go-ahead in New York before it can truly compete with neighbors over all potential revenue.

“While I understand the premise that there are other states that will be competing for the dollar, right now we’re not competing with states that already have [full legalized casinos],” he said. “If you look at Connecticut, they have two legalized full-scale casinos and people from New York go there, two and a half hours away. In Atlantic City, again, two, two and a half hours away – full legalized gaming. In Niagara Falls, full legalized gaming on the Canadian side – you’ve got tons of people upstate going over there.”

Split over benefits

Neither casino backers nor their opponents believe casinos will fully address the state’s fiscal problem. They do differ on the extent a full casino at Aqueduct—and elsewhere— might help.

“It’s not a cure-all for every financial ill that we have in the state but it’s certainly part of the solution,” Empire City’s Duffy says.

CAGNY’s Wellins has a very different take.

“There isn’t any quick fix,” she says. “We didn’t get into this mess overnight and we’re not gonna get out of it overnight. I mean, our government and our politicians are exploiting us.”