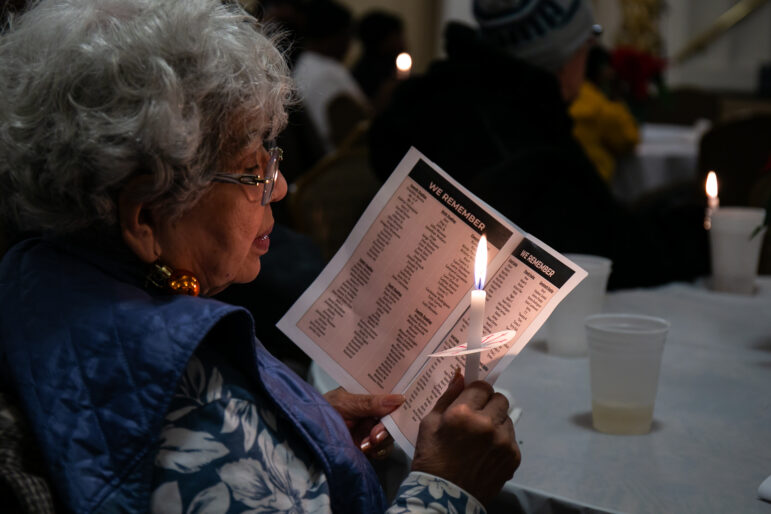

Photo by: Rain Rannu

The NYPD pulls over a livery cab in Queens. Street hails are common in the outer boroughs, but illegal, so drivers have to weigh the risk of getting a ticket that can wipe out a day’s profits.

Working as a livery cab driver is no path to riches, but Kingsbridge native Nancy Soria makes the most of it.

Before heading to work every morning, Soria, 39, gets her son, one of her three children, dressed and ready for the day. At about 8 a.m., she drops him off at school, and begins her job at 8:30 a.m. in her Lincoln Town Car.

Soria, who affiliates with Riverside Radio Dispatcher in Manhattan, works a six-hour shift daily, which she considers a part-time job, unlike her co-workers who commit to working a grueling 12 to 15 hour shifts. For the most part, Soria said she likes the hours because they conform to her son’s school day.

For three years, Soria has been doing the same routine, day in and day out. The pay is not lucrative—she makes less than $100 a day, sometimes substantially less—she loves to socialize and meet new people while doing her work, something that wasn’t part of her previous job as a newspaper carrier driver.

But like that previous job, Soria does get discouraged with the low pay, occasional lack of work and lack of health insurance. “Sometimes it really sucks,” said the Colombia native.

Soria shares her car with her children’s father, who operates the livery in the evenings. She says she will keep on working as a driver for a few more years until her son gets older before changing careers to do something else, perhaps going to college to pursue a career in translation. But other drivers may not have the same option. Jesus Calcano is one of those workers.

As a father of two children, Calcano, who affiliates with Excellent Car Service in the Bronx, cannot afford to go to school because business has gone down considerably for him, and therefore everything he makes goes to pay bills at home. If Calcano does not make a sufficient amount in a day, he just works more hours.

“If I can make $150, I can go home,” he said. “If I can’t, then I can’t go home. At times, I work more than 15 hours. To sit in a car for 12, 13 hours is not easy. Plus, you don’t eat well because you’re always eating food from outside.”

Still, driving around in his 2010 Toyota Camry searching for customers, Calcano, 43, said he likes aspects of the job. “I like driving and being outside,” he said in Spanish while listening to directions from his GPS to drop off a client one afternoon. “If [I] need to stop and do something or run an errand, I can do that.” But the work is made stressful by the possibility of getting a ticket.

“Before taking this job, I understood the type of repercussions that could happen,” said Calcano, a native of the Dominican Republic who has been driving for 10 years. “I do the job because it [is] a good way of making an income to help me and my family.”

Indeed, both Calcano and Soria face the problem that it currently is illegal for them to pick up street hails in the outer boroughs, which they both serve.

That law might be changing: With the backing of the Bloomberg administration, the state legislature has called for offering permits to 30,000 livery cab workers to pick up people legally. The bill was opposed by some yellow cab drivers and owners who say the measure will reduce the value of taxi medallions by creating a new class of cars to compete with yellow cabs for street-hail customers. They may mount a legal challenge to the law.

A spokesperson for the Livery Base Owners Association, Cira Angeles, said the organization wants to make sure that livery cabs workers have the same opportunity as yellow cab workers, which is to pick up customers legally, something that she says livery cab workers have been doing illegally “for the last four decades.”

“We’re talking about a business that depends a lot on [being] in the street,” Angeles added.

For now, livery cab workers Soria and Calcano will continue working to do the daily routine they have come to know, even if it means facing possible future infractions.

“We are trying to work hard,” said Soria. “We are not delinquents.”