Photo by: HRA

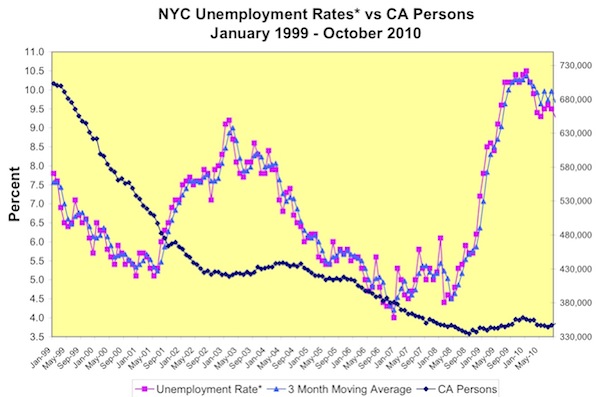

A chart from the Human Resources Administration website contrasts the rise in the local unemployment rate with the decline and stability of the number of people on welfare in New York.

In last week’s State of the City address, Mayor Bloomberg pointed with pride to the fact that despite the economic downtown, his administration has “kept the welfare rolls at historic lows.” Over the past 15 years, cash assistance rolls have shrunk from 1.1 million to barely 350,000—a figure that conveys the city’s commitment to “work first” policies that began under Rudy Giuliani and have continued under the current administration.

But documents released to City Limits reveal that even under the famously data-driven Bloomberg, there’s much that the city can’t answer about who’s applying for welfare—and what happens to them when they do.

It can’t say whether more or fewer people are applying for welfare today than did three years ago. It can’t say how many people who dropped their welfare applications did so because they got a job, and not because of bureaucratic hurdles. And it can’t say how often its computers—without any human intervention—automatically reduced or revoked welfare benefits.

The documents were prepared by the city Human Resources Administration (HRA) following a hearing of the City Council’s General Welfare Committee last September, at which HRA Commissioner Robert Doar was peppered with questions from councilmembers on obstacles to poor New Yorkers receiving public benefits, but provided few details, saying he hadn’t brought specific figures with him.

Finally, an exasperated Councilmember Brad Lander said: “Are they applying or are they not applying? And if they’re applying, what are we doing for them?” Replied Doar: “We will be happy to do a letter on those detailed statistics.”

True to Doar’s word, two detailed letters eventually arrived, responding to both Lander’s questions and to a set of queries posed by General Welfare committee chair Annabel Palma, filling 13 pages with replies on everything from city job placement numbers to how many welfare recipients are approved for enrollment at CUNY schools.

But on the central questions of whether more people are applying for benefits, how many applicants the city turns down and why some people get kicked off welfare, the results were somewhat disappointing. While all questions received answers, many were incomplete or amounted to admissions that the agency didn’t compile the requested information.

And though HRA officials beg to differ, an analysis of the HRA letters—and information subsequently provided directly to City Limits by the agency—leaves the undeniable impression that the city’s record-keeping on services to the poor remains riddled with holes, making it difficult to determine which policies are successful and why.

Among the central questions posed to HRA, and the agency’s responses:

Are more people applying for welfare since the economic downturn, and are they getting it?

This was the heart of Lander’s line of questioning, and HRA dutifully provided figures: In 2009, the agency received 366,227 applications for cash assistance. For first nine months of 2010, there were 261,857 applications.

As to whether how this compares with prior years, though, HRA pleads ignorance: It wasn’t until October 2008, officials say, that its decade-old Paperless Office System was set up to report application numbers, meaning the agency has no reliable record prior to that date.

Interestingly, the state Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance keeps its own records for earlier dates, which shows 368,639 applications for the time period from July 2007 through June 2008. And though the figures aren’t directly comparable—the city and state use different sources to count applications—this would imply that applications are going down even as unemployment more than doubled and poverty rates soared.

How many applicants are denied welfare, and why?

HRA has pointed with pride to the fact that welfare rolls remain near record lows despite the severe recession. But some wonder if people in need are simply being denied help.

In answer to questions about the rate at which it denies those who have applied, HRA said that in 2009, 56 percent were accepted, 42 percent denied, and 2 percent withdrawn. In the early part of 2010, 54 percent were accepted, 44 percent denied, and 2 percent withdrawn. The state OTDA figures from fiscal 2008 indicate a 64 percent approval rate, suggesting that denials went up as the recession wore on—though again, city and state data aren’t easy to compare.

Then there’s the question of why HRA turns down the people it denies. In response to Lander, HRA noted that it has “over 90 codes specifically for denials of applications.” These can include everything from “failure to comply with job search” to “failure to cooperate with substance abuse treatment referral” to “failure to keep eligibility verification appointment.”

However, the HRA letter then lumped together all of these 90 codes into just five categories, with nearly two-thirds falling into the broad area of “non-compliance.”

Public benefits analysts say that breaking down that “non-compliance” figure into a more fine-grained accounting—how many denials were because applicants had missed an appointment, say, and how many because they failed to provide necessary documentation?—would help explain why nearly half of all welfare applicants end up getting denied assistance.

“People don’t apply for welfare unless they have no place else to turn,” says Liz Accles of the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies, who’s conducted her own analysis of the HRA-Council correspondence. “Those codes wouldn’t paint the whole picture, but they should at least show where people are falling off in the process.”

Yet when City Limits subsequently asked HRA for a more detailed breakdown, an agency spokesperson replied that the city does not track denials by each of the codes. Asked whether knowing the details of why applications are rejected wouldn’t provide useful feedback about the effectiveness of city benefits programs, Doar told City Limits, “It might. Sometimes when you run programs that are complicated, you can get overwhelmed by the minutiae, and it can lead you to lose focus on the core objectives. But there’s no question that we have lots of data, and that we analyze what we do have carefully.”

Is HRA cutting off families’ benefits for no reason other than agency record-keeping errors?

This is a big one. For years, advocates for the poor have charged that so-called “autoposting”—reductions of welfare benefits that are automatically imposed by computer systems for missed appointments unless case workers actively note that a client has attended—have led to a flood of erroneous case closings.

“Often clients are hit with a sanction despite having attended an appointment or having received an excuse for their absence from their worker because the worker fails to record the attendance or excuse in the computer,” Legal Aid Society staff attorney Kathleen Kelleher told Palma’s committee in September. “Sanctions also happen when HRA sends appointment notices to an incorrect address—even though the client has informed HRA that her address has changed. Because the system of autoposting automatically assumes a client has not attended an appointment unless a worker corrects the system and ensures that attendance was recorded, all errors in this system run against the client rather than HRA.”

On autoposting itself, HRA insists that since all of its systems are automated, it can’t filter out computer-generated sanctions from worker-generated ones. Susan Welber of the Legal Aid Society, which has a pending lawsuit against the city charging that autoposting violates constitutional due process rights, says she doesn’t buy it: “The autoposting, by definition, is computer code-driven. So they definitely can generate statistics on the various categories of autoposted appointments.”

In any case, there are other clues to the number of erroneous penalties. When clients apply for “fair hearings”—a state-run appeal process in which both sides appear before a judge to decide whether HRA’s ruling was justified—more than 12 percent of HRA’s decisions are overturned, while nearly 60 percent are withdrawn by the city, according to HRA figures provided in its letter to Palma.

Before applying for a fair hearing, though, there’s an intermediate step known as “conciliation,” where clients are called in to HRA to discuss their pending loss of benefits with agency workers. This, according to many legal advocates for the poor, is where autoposting rears its ugly head.

If a client misses an appointment for any reason (or an HRA worker fails to note that they were present), the HRA computer automatically issues a “failure to report” code, and a conciliation notice is sent to the client’s address. If the client doesn’t show up for that, the computer generates a notice of intent (or NOI) to cut off their benefits.

“You can see the danger in that,” says Welber. “Many cases where clients are getting sanctions or getting their cases closed, it’s because HRA has the wrong address. And so there’s no opportunity for the client to intervene. They don’t get any of these notices—they don’t get the original notice scheduling the appointment, they don’t get the conciliation notice, they don’t get the NOI, and then they get their case closed or sanctioned.”

Many of these clients ultimately file for fair hearings and win, recouping lost benefits, though often after weeks or months without a check. How often this is happening is impossible to tell, though: HRA told the Council that “current HRA data does not capture incorrect agency action during conciliation.”

Moreover, HRA officials tell City Limits that the agency doesn’t track what percentage of clients fail to show up for conciliation meetings; Doar would only say that “in conciliation, during the course of the past year, the majority of them resulted in the agency being able to settle the matter with no penalty to the client.”

Are people who enter HRA’s job placement program getting placed in jobs—or even making it through the program?

HRA’s Back-to-Work program has been a prime target of the agency’s critics, with the low-income membership group Community Voices Heard charging that most participants drop out before getting anywhere near a job.

HRA’s figures provide some ammunition to such claims, though their figures are somewhat less dramatic than CVH’s claim: 16 percent of welfare recipients ordered by HRA to report to its Back-to-Work program “fail to report”; of those who make it in, 60 percent “infract” from the program before finishing, but the agency contends that many of those drop-outs find work during the process.

“It would really be a misinterpretation of the role of Back-to-Work to say that because only a small group go through the program in an extended way that all the ones who don’t are somehow a failure,” Doar says. “The existence of the Back-to-Work program is what often leads people to make choices on their own, to find employment or take employment that becomes available to them through their own devices.”

So how many of those 60 percent left because they found employment? Here too, HRA says it doesn’t keep track. On request from City Limits, the agency did report that in the first 11 months of 2010, 64,032 clients were “enrolled and assessed” by Back-to-Work, of which 12,736 found jobs that lasted at least 30 days. If sixty percent of enrollees didn’t finish the program, that would make 38,419 dropouts, meaning that less than one-third of those who dropped out did so because they found steady work—and HRA has no idea what happened to the rest.

So what does all this add up to?

Doar insists he’s happy with the statistics his department compiles. “I think that the data system that we’ve developed at HRA is as detailed and sophisticated as any in the country,” he says. “And over the years, it has helped us help hundreds of thousands of applicants and recipients of cash assistance find employment.”

Lander is far less sanguine, and wonders whether the holes in the data are just the slightest bit intentional.

“This is an administration which has prided itself on making it harder to access benefits as a strategy for management,” he says. “This is something they’ve carried over from the Giuliani administration: if you make it more difficult to get a benefit, some people will be able to do without it. When the data suggests they’re doing that, and then you can’t get any more information, then you have to believe that there’s something going on at a deeper level.”

Lander remains especially frustrated that basic questions are still going unanswered: “Why are people dropping out, or unable to comply? That would help us a lot to know how to provide the right kinds of assistance to people.”