Photo by: Neil deMause

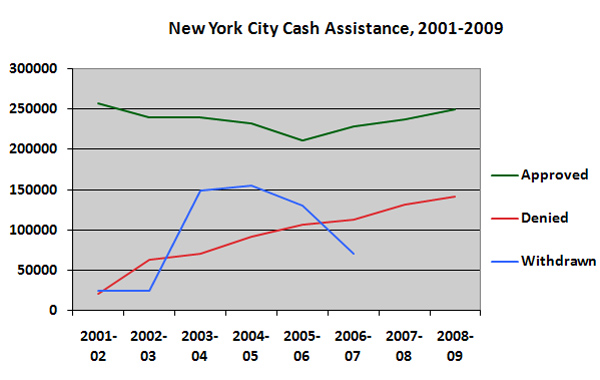

Figures from the state Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance show a steadily climbing number of approvals and denials of welfare in the city. (OTDA stopped reporting withdrawn cases in its 2008 report, according to a spokesperson, “due to uncertainty with those numbers.”)

On one thing there is no argument: Since 1995, when it reached a peak of 1.1 million, the number of New Yorkers receiving cash assistance has dropped dramatically, falling to a low of 334,000 in late 2008 before rising slightly and then falling again during the recession.

But despite the passage of years since the Giuliani administration launched welfare reform, and substantial policy changes under Mayor Bloomberg, a fundamental issue still divides city welfare officials on the one hand, and some New Yorkers receiving welfare and the social-service workers who advocate for them on the other: Is the city blocking people from receiving benefits to which they are entitled?

The dispute was on full display last week at a much-delayed hearing of the city council’s General Welfare Committee, at which advocates had far more questions about the city’s benefits system than the Bloomberg administration had answers.

The concerns about eligible people being denied help was first raised in days of Mayor Giuliani, whose tactics included sending fraud-detection workers to visit applicants’ homes unannounced and issuing worker manuals defining “diversion” (i.e., keeping people from applying for welfare) as welfare workers’ primary goal.

Bloomberg eliminated many of those policies, and has massively expanded outreach on food stamps and Medicaid access, with the result that both programs now reach many more New Yorkers than when Bloomberg took office. Yet the number of cash assistance recipients, after a slight rise at the start of the economic crash, is again falling, and some welfare experts charge that the city’s “work first” policies present too many roadblocks for those seeking aid.

At times, the Council hearing itself seemed to face insurmountable obstacles. Initially slated for June, it was hurriedly re-slotted into the council’s September calendar just a couple of weeks ago—so hurriedly that all of the Council’s usual meeting rooms were already booked. As a result, when committee chair Annabel Palma opened last Monday’s session, the overflow crowd was squeezed into a kitchen on the 16th floor of the government building at 250 Broadway, with some spectators perching on tables alongside signs reading “Do Not Unplug The Ice Maker—IT WILL CAUSE A FLOOD.”

A picture of progress

First to testify was Human Resources Administration commissioner Robert Doar, who painted a customarily upbeat picture of the city’s efforts to aid its needy. Increased outreach has succeeded in providing food stamps and health insurance benefits to hundreds of thousands more New Yorkers; job placements are up, he said, because the “health, education, and hospitality sectors” have rebounded well from the recession, while the city’s “work first” approach to welfare applicants “has been successful, even during the economic downturn, largely because certain job sectors have remained strong.” He also revealed that HRA will soon begin working to send welfare recipients to the Small Business Administration’s Workforce 1 job centers (which funnel job seekers to small businesses seeking employees)—an announcement that brought a loud “Yay! Finally!” from Councilmember Gale Brewer.

“We have one of the highest grant levels in the country, yet have one of the most lenient sanction policies,” said Doar, referring to policies on when recipients have benefits reduced or suspended for failing to comply with work rules. “HRA will continue to meet the needs of the city’s low-income families, while remaining committed to the lessons of welfare reform, and our work-first approach to fighting poverty.”

Those seeking more details about HRA’s achievements, however, would have to wait for another day. Time and again, councilmembers who pressed Doar for specifics got the reply: “I can get that for you.” At one point, after Doar said he didn’t have data on hand regarding what percentage of welfare applicants are rejected, a visibly frustrated Councilmember Brad Lander complained, “What I thought today’s hearing would be was, it seems like more people would be applying for benefits in a time of recession. Are they applying or are they not applying? And if they’re applying, what are we doing for them?” Doar’s answer: “We will be happy to do a letter on those detailed statistics.”

Many of those statistics, though, are in plain sight on the website of the state Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance, in its annual report to the legislature. According to the OTDA figures, cash assistance applications in the city are indeed on the rise, but denials of benefits are rising even faster, reaching 36.2 percent of all non-withdrawn applications in the year ending June 2009.

At another point in the hearing, pressed by Palma on a 2007 report by the low-income membership group Community Voices Heard (CVH) that 60 percent of “failure to comply” notices to participants in HRA work programs were found to be in error, Doar remarked, “I have to review that. I don’t remember that particular statistic”—though his top staffers had previously strenuously criticized the CVH figure as inaccurate. (HRA says it will supply responses to these and other questions from councilmembers later this week.)

A different view

After nearly an hour and a half of testimony, Doar and his entourage of top staff departed (along with much of the audience, and several committee members—only Palma and Lander stayed for the entire hearing). “I’m really sorry and upset that Commissioner Doar and his people had to leave,” said the first non-City Hall panelist, Ann Valdez, a CVH member who described herself as being on public assistance for “too many years” following an escape from an abusive relationship. “I think he’s somewhat disconnected to what actually goes on at the centers. He really has no idea what goes on there.”

As one example, Valdez cited her experience at an HRA-contracted training program. “They get paid for participants coming five days a week. Didn’t happen. You went two days a week, sat there for two hours and went home. You’re getting a training in computer skills, typing, data entry? No, you weren’t, because half of the computers didn’t work. So you sat there, you checked in, you went home.”

Similar stories came from legal aid attorneys and other nonprofit advocates, who provided detailed counterarguments to Doar’s claims.

Asked why many people never complete the application process for welfare benefits, Doar had said, “usually they’re ‘did not return’ and ‘denied.’ And why they did not return, that I’ll have to look into.” Liz Accles of the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies noted one likely reason: When the city’s required “upfront job search” for applicants deemed employable is included, “you’re talking about 26 [appointments], 20 of them being full-day, full-time appointments, that if you don’t adhere to, it’s likely your application will be rejected.”

Doar had boasted of providing application materials in seven languages; Legal Services of New York government benefits coordinator Tanya Wong said a 2007 study by her office found that most city job centers didn’t provide applications in all languages, adding that “our limited-English-proficient clients consistently report being told to bring their own interpreters with them to the welfare center, and are frequently forced to rely on their children to interpret for them, in violation of Local Law 73.”

A call to the speaker

Nearly four hours after the hearing convened, corroboration for Doar’s critics came from an unexpected source. “I came today to just listen. I hadn’t planned to testify, because I’m still an employee of the system,” said Edwin Pearson, an administrative law judge who conducts fair hearings for applicants challenging HRA rulings. “But I really couldn’t go home tonight and sleep properly after I’ve heard all the testimony that’s been given today. … I hold about a thousand fair hearings a year, and everything that all the legal services people said, the report from CVH that you quoted, is right on target. I see that day in and day out.”

Nearly every panelist included recommendations for reform, from streamlining the cash assistance application, as has been done for food stamps and Medicaid, to conducting a Council investigation into the computer-driven “autoposting” that automatically cuts off benefits unless a city worker properly enters a note that an applicant has met all of his or her requirements. Palma, at least, expressed an eagerness to act, saying after the hearing that she planned to approach Speaker Christine Quinn about setting up a mandatory tracking system to find out “how many people are applying for public assistance, how many are being denied, why they’re being denied, and what’s happening to those people.”

Palma said she was especially interested by the testimony from Brooke Richie, director of Resilience Advocacy Project, a youth advocacy organization, who said that young applicants for benefits are being routinely—and illegally—told by city workers that they need to be 21 to apply. “That’s my story,” explained Palma. “I was a 17-year-old with a baby and I went to apply for public assistance and was totally denied. And until today I wasn’t aware that it was illegal to do that.”