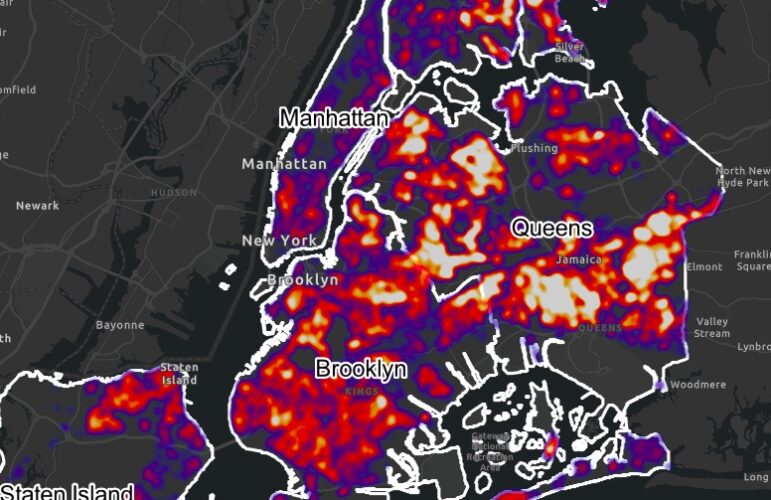

When the New York Police Department first announced plans for a new network of 3,000 surveillance cameras and sensors throughout lower Manhattan three years ago, skeptics voiced concern over wholesale, unregulated monitoring of innocent citizens.

Modeled on London’s 10,000 camera system, called the “Ring of Steel,” the Lower Manhattan Security Initiative (LMSI) – which has attained the same nickname – will consist of 3,000 networked cameras monitoring 1.7 miles of area south of Canal Street. One-third of the cameras will be city-owned, with the other two-thirds belonging to private businesses, termed “stakeholders” in the guidelines. Automated license plate readers and environmental sensors will also provide data to the police. The cameras will be monitored by officers at a coordination center on Broadway, which opened last November. The system is expected to cost $89 million in local and federal funds.

To allay concerns about the intrusiveness of this network, the NYPD last month made public a preliminary version of the Public Security Privacy Guidelines for the Domain Awareness System, the program that will handle all data gathered by Lower Manhattan Security Initiative cameras. Comments on the draft will be accepted through next Wed., March 26 (and may be e-mailed to oct@nypd.org or mailed to New York City Police Department, Attention: Counterterrorism Bureau, 1 Police Plaza, New York, NY 10038).

According to the draft guidelines, the data management program is a counterterrorism measure intended to deter future attacks, detect “pre-operational” terrorist activity, increase “domain awareness” for non-police entities involved in the program and provide an infrastructure for the “integration of new security technology.”

The system will gather and store information from cameras, automatic license plate readers, environmental sensors and other unspecified technology. Video data will be erased after a 30 day “pre-archival period,” unless footage is being used in law enforcement investigations. License plate data and “metadata,” a broadly-defined category of information that will “increase the usefulness” of footage or sensory data gathered, will be retained for five years. Environmental data may be retained indefinitely.

(For more on surveillance in New York City, see Near and Present Danger: Freedom In Today’s City, City Limits Weekly #646, June 30, 2008.)

Despite the NYPD’s assurance that data from the Domain Awareness System will be strictly regulated and the cameras will not be used to target innocent citizens, surveillance skeptics including the New York Civil Liberties Union remain unconvinced about the department’s commitment to privacy.

“They purport to be nothing more than internal NYPD policy. There are no actual restrictions here,” NYCLU associate legal director Christopher Dunn said of the privacy guidelines issued by the police department. Dunn, who is lead counsel on the NYCLU’s 2008 lawsuit to obtain information about the Ring of Steel, says the police department broadly defines the data it will retain: “Ninety-nine point nine percent of what they collect will be lawful activity.”

Deputy Commissioner for Public Information Paul Browne did not respond to requests for further comment on the LMSI project and its privacy guidelines.

City Councilman Alan Gerson, whose lower Manhattan district includes the designated area, says he views the NYPD’s guidelines as a first step toward ensuring that video surveillance is done properly. “It’s important that this not be allowed to evolve into a general surveillance system, but rather be used to identify and prevent real threats,” Gerson said.

He plans to introduce legislation in the next few months that would codify regulations and restrictions for video surveillance in the five boroughs. Asserting council oversight over the practices of the police department – rather than leaving surveillance policy solely in the hands of the Bloomberg administration – is another reason Gerson is pursuing this issue. “We need to maintain these checks and balances,” he said.

As it stands, only authorized NYPD and Stakeholder personnel will have access to LMSI facilities and data. Both are required by the guidelines to complete unspecified “privacy training.” The guidelines prohibit targeting individuals by race, color, religion, national origin, gender or political beliefs, among other criteria. The Domain Awareness System will only monitor “public areas and activities.” Violations of the privacy guidelines will be met by “appropriate disciplinary action,” according to the document.

The use of cameras for counterterrorism purposes has not been formally evaluated, according to NYU Sociology Prof. David Greenberg, who co-authored a report on video surveillance and its impact on crime in Peter Cooper Village and Stuyvesant Town. However, Greenberg has doubts about the NYPD’s claims that the Ring of Steel will deter potential terrorists from acting: “Would someone who wants to blow up a building in lower Manhattan be deterred by cameras? It strikes me as unlikely,” he said.

Studies on the effects of video surveillance on non-terroristic violent crime have indicated that cameras do not prevent crime, and at best, displace it to other locations. A University of California-Berkeley report on the San Francisco Police Department’s blue-light cameras found that homicides decreased within 250 feet – but outside that range, homicides spiked.

Video surveillance does have its uses for evidentiary purposes: the perpetrators of the July 2005 suicide attacks in London and the Dec. 2008 massacre in Mumbai were caught on camera. For investigations, said Greenberg, video footage has “some potential value.”

The LMSI also represents the ascendancy of public-private security partnerships. The “stakeholders” described in the guidelines will sign memoranda of understanding with the NYPD permitting them to share footage from their cameras and have access to data gathered. They will also sign a confidentiality agreement. Stakeholder representatives will also have physical access to the LMSI coordination center. It is not clear whether the content of the memoranda between Stakeholders and the NYPD will be made public.

All other parties seeking access to the data must be approved by Deputy Commissioner for Counterterrorism Richard Falkenrath.

Allowing private industry access to law enforcement data creates “tremendous potential for abuse,” according to attorney Dunn, particularly when the identities of Stakeholders are not known to the public: “You’re merging private companies into law enforcement,” he said.

In spite of the economic crisis and New York City’s deep budget cuts, the LMSI’s installation is proceeding as planned. About 300 of the 1,000 planned police cameras have been installed so far. The city’s budget crunch has also slowed Commissioner Ray Kelly’s plans to shift 800 officers from beats elsewhere in the city to bolster security in lower Manhattan. Presently, 30 automated license plate readers also are in operation.

The city recently canceled the January 2010 police academy class, and will go through 2009 with fewer officers on the street – but more cameras. This set of priorities troubles Chris Dunn: “You have to wonder at a time when they’re laying off cops, whether it makes sense to spend this money on a camera system.”

One thought on “A Chance For Input On 3,000 New Police Cameras”

Pingback: Transparency Advocates Win Release of NYPD “Predictive Policing” Documents | Go to Ground