Photo by: Aaron McElroy

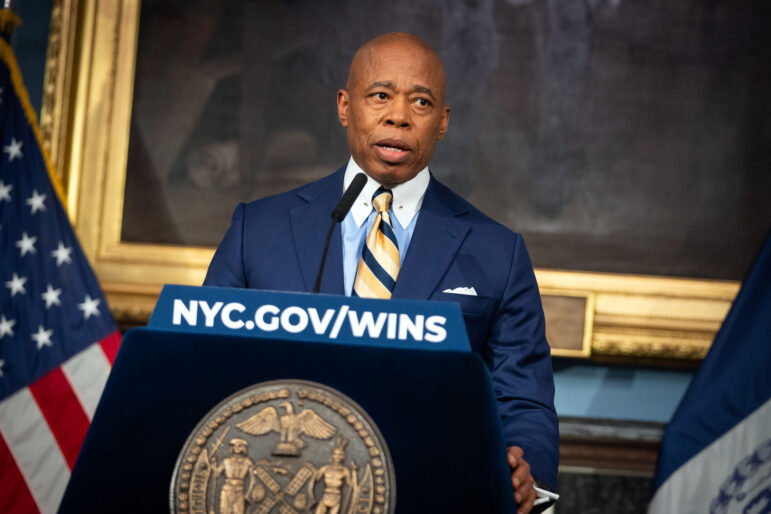

Like most city bridges, the Brooklyn Bridge is under the watch of cameras. But citizens are often restricted from doing their own filming of area bridges.

The horse was named Ruthless. With jockey Gilbert Patrick on its back, it rounded the course in three minutes five seconds to win the very first Belmont Stakes in 1867—back when the race took place on a spot of ground in the North Bronx called the Jerome Park Racetrack. Twenty-three years later, the track closed because the city needed Jerome Park for a reservoir. Now there’s a notion to bring racing—or at least jogging, and perhaps some walking—back to the site. The city is improving all the parks in the area, and some neighborhood activists want a track around the water’s edge. But the Department of Environmental Protection is blocking their plan, citing post-September 11 security reasons.

There is, of course, no constitutional right to run around a reservoir. Nor is there one for taking pictures of bridges, driving down a street, bringing a bag into a baseball stadium or wheeling your baby stroller along a sidewalk without having to bob and weave around fortifications designed to stop kamikaze truck bombers. But these are some of a long list of mundane things that, before September 11th, New Yorkers used to do, or might have done more freely. The fear of terrorists permeates places and conversations where it was once barely present, if at all. In 2007, the city’s Department of Correction cited “imminent security threats” in winning rule changes that allow it to listen to prisoners’ phone calls, read inmates’ mail and censor publications. Not just bags, but also knitting needles, are verboten at Yankee Stadium. The NYPD is pushing to require a permit for the use of air-quality-testing equipment, which became popular after the 2001 attacks, ostensibly because the machines could trigger false alarms.

Opponents of the Atlantic Yards development in Brooklyn trumpeted terrorism fears as one argument against building a major sports arena there. Worries about a biology lab that might handle dangerous substances—and therefore prove a juicy target for Al Qaeda—were one talking point for foes of Columbia’s planned West Harlem expansion. When the Department of Education wanted to ban cell phones in schools, parents rebelled, citing the need for families to be in touch if another September 11 befell the city. In December, a City Limits photographer tried to take a picture of the outside of a public high school; a school safety officer stopped him. “No,” he said. “Not since 9-11.”

Sometimes these fears drive public policies that reshape the city’s streetscape, or what we can do in it. Almost immediately after September 11, the city’s Office of Emergency Management and the NYPD asked the state department of transportation to close the East 15th Street exit of f the southbound fDR Drive, which runs near a Con Edison plant. Now the agencies are discussing a permanent closure of the exit.

The police department vetoed the first design for the freedom Tower; the revised version features blast-resistant metal sheeting around a lobby that was once supposed to be glass. Pre-September 11, the NYPD did not publicly weigh in on the design of buildings. “Up until six years ago, I didn’t have any interest in glazing, fenestration and things of that nature,” NYPD lieutenant Patrick Devlin told the Protective Glazing Council Annual Symposium last November, according to Glass magazine. “After September 11, I wanted to learn about this. In February 2002, we didn’t have a counterterrorism bureau. Today, I have 16 investigators dedicated to infrastructure, two of whom are structural engineers.”

There’s no arguing with some of what the city has done, like revising the city’s building and fire code to expand the number of buildings with sprinklers and improve building evacuation procedures and. Other steps haven’t been universally accepted. Chinatown business owners and residents have jostled with the police department since September 11 about the blockading of Park Row, the closure of a municipal parking garage and a park near One Police Plaza, and extensive police parking in the neighborhood. Neighborhood activists have won some concessions through court action but claim that more than 30 businesses have been forced to shut down because of the street closures. “It’s changed the neighborhood, the economy, quality of life,” says Jeanie Chin of the Civic Center Residents Coalition.

Sometimes, however, it’s the public—not the police—that pushes for more security. In a 2007 interview, Michael Sheehan told the trade website Buildings.com that while he was the NYPD’s counterterrorism chief from 2003 to 2006, he told most building owners not to worry. “They didn’t need more security. I rejected proposals for surrounding most buildings with Jersey barriers. More often than not, I recall telling some owners to just chill out,” he says.

If every building owner took Sheehan’s advice, it would be bad news for the private security industry. But the past few years have been anything but bad for the people who sell protection. At a May convention at the Javits Center, firms offered everything from “covert surveillance” to blast curtains meant to stop the flying glass that kills most bomb victims. Customers could buy truck barriers that will work at 30 miles per hour, or upgrade to the 50-mph version. Also on of fer were metal mesh for layering the insides of walls—lest someone sledgehammer through the exterior—and a scanner that identifies employees by mapping the veins in their hands.

Give the security industry credit for one thing: It has a good read on what people fear. Publicity material for the security consultancy Aggleton & Associates asks particularly pertinent questions: “What does the threat level mean to my firm and my facility? How much security is appropriate to the real threat? What do I do as the threat level changes?”

“Will we ever go back to normal? What is ‘normal’ today?”

Greg Faulkner, who oversees a committee of community leaders charged with monitoring the new Croton-water filtration plant that will link to the Jerome Park Reservoir, sits in the middle of the fight over the running track. Building the filtration plant in Van Cortlandt Park was controversial, so the Bronx is getting $243 million to improve parks; $2.8 million of it is set aside to create a path around the reservoir. The question is whether that path will be inside either of the DEP’s two rings of security fences around the water, or on the outside looking in. “DEP is saying it’s a security concern based on September 11 and, based on the world situation now, that to have public access to the reservoir would be problematic since the water coming out of that reservoir goes to people very quickly,” Faulkner says. “People say that other reservoirs have [public] access upstate. DEP’s response is those reservoirs don’t enter the system as quickly, so if you had a problem, you could divert it.”

The DEP has not described a specific scenario for what could happen if the track were built too close. “DEP’s policy on a track at Jerome Park Reservoir came about after consultation with officials at all levels of government, including the Department of Homeland Security, the FBI, EPA, the NYS Department of Health and NYPD,” says DEP spokesman Michael Saucier. “All were uniform in their concern over public access to such a critical aspect of the drinking water system.” The EPA recently announced it was granting $12 million to New York City to protect its water system.

Park activists note that since the reservoir contains up to 773 million gallons of water, a terrorist would have to dump a few freight cars’ worth of poison into the water to actually harm anyone. But when it comes to fears of terrorism, the actual risk factor doesn’t matter, says Faulkner, who says he’s neutral in the dispute. “If you’re talking about any kind of terrorist threat, it’s not that something causes damage, it’s the threat,” he says. Even a rumor about the reservoir being poisoned could be destructive, he argues. “Can you imagine the panic that would set of f in the community—even if, in fact, there would be very little threat?”