Courtesy Kevin Cleare

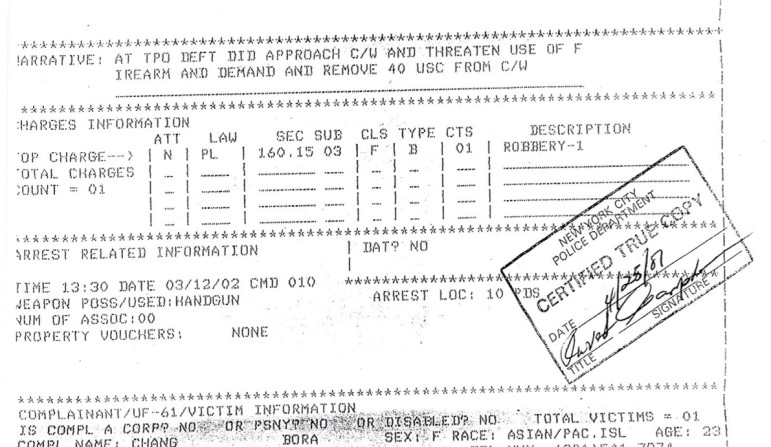

A section of Kevin Cleare's much-mistaken rap sheet.

Kevin Cleare’s bid for the fresh start he’d been led to believe he’d earned by the five tough years he’d served in prison hit road bumps almost immediately. Back home in 2007 after serving his sentence for an attempted robbery at the age of 21, his plan was to attend school, land a job and walk the straight and narrow. Instead, it took almost seven years, as he marched from a police precinct to district attorneys’ offices to courthouses in an effort to clear up mistakes that had somehow burrowed deep into his criminal record history—mistakes that would bar him from schools and jobs. Worse, he feared, they might even send him back to prison.

The rap sheet mistakes consisted of three arrest entries that were listed as open and still pending, even though they had already been resolved by his earlier conviction. His confusion deepened because the dates listed for the arrests were for a period when he’d been locked up at Rikers Island, when he knew he had not been arrested for new charges.

“I was extremely nervous about the situation,” he says. “I spoke to my family about it. They looked into it as best they could. They just got the run around, a lot of misinformation.”

Friends of the family directed Cleare to The Legal Action Center, an advocacy group that assists individuals with mistakes on their rap sheets. Sebastian Solomon, at the time LAC’s senior paralegal, confirmed for Cleare that until the mistakes were remedied the open cases would raise potential questions for employers. There was also a possibility he could still be arrested for them. Cleare and Solomon set out on a quest to fix the problem.

Their first stop was the 10th Precinct in the Chelsea section on Manhattan’s West Side where Cleare had first been arrested five years earlier. The hope was that police, who record arrests in their own database known as Omniform, would be able to quickly resolve the problem by looking up the number assigned to the arrests.

“They looked at us like we were crazy,” says Solomon. “They had no idea what we were talking about.” Instead, they were told to try the impossible by tracking down the officers who had busted Cleare originally, or to visit One Police Plaza.

A visit to One Police Plaza seemed the only viable option. Solomon and Cleare were initially directed to an office on the third floor where computerized records were held. Data entry employees there were astonished to see members of the public and bluntly suggested they go elsewhere. They next visited the NYPD’s freedom of information office. There they waited for hours without getting assistance and [were] ultimately had to leave without the information they sought. Still trying to follow the trail of the arrest data, their next stop was the Manhattan district attorney’s office. After booking a suspect, police send the arresting information to the local prosecutor. There, either a criminal complaint is issued or the DA declines to prosecute.

Bult/Goldensohn

Kevin Cleare

In Cleare’s case, however, the DA was unable to connect the added arrests to the case for which he had already been prosecuted. Officials there offered no help at resolving the problem.

Their last shot, Solomon figured, was the courts, where there is a pathway to correcting errors if a disposition can be obtained showing how the case was handled. But that only works if the case can be located in the system. If the case was never docketed, there’s no court mechanism to find it. At the courthouse, there was no record of any court cases filed as a result of the added arrests. This confirmed for Solomon that the subsequent arrest charges had never been linked to the prosecution. It was another dead end, with no other options in sight.

Legal Action Center’s senior staff attorney at the time was Judy Whiting, who has since moved to the Community Service Society where she is general counsel. Whiting took her own stab at cracking the case, writing to NYPD’s Deputy Commissioner for Legal Affairs regarding Mr. Cleare’s situation. Her query went unanswered. With all avenues leading to dead ends, the matter languished.

But the situation continued to bother Solomon. In late 2013, the Legal Action Center, along with other groups advocating for people like Cleare, obtained a meeting with top staff of Manhattan District attorney Cyrus Vance’s office to talk about various problems, including rap-sheet errors.

In a follow up meeting, Solomon offered Cleare’s case as an example of the often-intractable difficulties faced by those trying to clear up mistakes on their record. A request was made for the prosecutor’s office to take one more look for the elusive records of Cleare’s arrests. A few months later, the DA sent a letter to the state’s Division of Criminal Justice Services, the official repository of criminal records, stating that the arrests were a mistake and that their office had no intention of prosecuting Cleare on the matters. DCJS took them off the rap sheet.

“It was a little bit of a personal mission,” Solomon says of the saga. But the mission was accomplished: The proof was finally on paper.

Cleare, who now works as a mental-health counselor for the city and is studying social work at a CUNY college, says the long journey helped him begin to understand the biggest barrier to remedying errors in criminal records: “When they don’t know how to fix a problem, they won’t admit it’s a problem,” he says.

This story is part of a series by

a class on urban investigative reporting at

the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism

taught by Errol Louis and Tom Robbins,

who served as editors.

* * * *