The mayor’s office said sleeping on the floor could be a fire hazard. But the rules appear to be sowing confusion, at least at one overnight site in Brooklyn, where residents were told earlier this month that they weren’t allowed to sleep before 2:30 a.m., according to a video obtained by City Limits.

Daniel Parra

A sign posted outside the city’s reticketing center in the East Village, where migrants can request another shelter placement, advising those who need a place to stay overnight to visit a Brooklyn church now being used as a drop-in center.Lea la versión en español aquí

New York City’s road to compliance with a new settlement on re-sheltering recently arrived immigrants has been bumpy: the administration already missed a court deadline to eliminate the waiting list for those seeking a bed.

Now, the mayor’s office is encouraging migrants to sleep in chairs rather than on the floors of the city’s “drop-in” centers—sites, often with few services and amenities, where those awaiting a new bed or who need a temporary place to stay can spend the night—City Limits has learned.

On April 8, New York City began transitioning to new shelter rules for recently arrived migrants, required as part of a legal settlement after months of negotiations between the city and homeless advocates over New York’s right to shelter.

For decades, that right obligated the city to provide a bed to anyone who needs one, at least temporarily. But the Adams’ administration argues it was never meant to apply to the “extraordinary circumstances” the city now faces, with tens of thousands of new immigrants who’ve entered the shelter system over the last two years.

Under the new settlement terms, newly arrived immigrants without children reapplying for a bed after initial 30- or 60-day stays may only qualify for an extension under “extenuating circumstances”—like if they have an upcoming medical procedure, immigration hearing or have made significant efforts to move out of shelter. Officials told City Limits earlier this month that they’re still working to set up a system to make those assessments.

Under the new settlement terms, those waiting to secure another shelter stay can now spend the night in one of three overnight drop-in or “hospitality” centers, according to City Hall.

While the right to shelter settlement agreement requires the city’s emergency shelters meet minimum standards—such as adequate staffing ratios and access to showers and cots—the now-called “drop-in centers,” don’t have the same requirements.

Instead, they operate like other Department of Homeless Services drop-in centers, where people can come indoors for the night and sleep in a chair, but there are no beds since it’s a temporary space and is not considered a shelter, explained Josh Goldfein, an attorney at the Legal Aid Society, one of the organizations that negotiated the right to shelter settlement.

Before the March court decision, migrants who reapplied often waited days or weeks for another placement, spending their nights at one of five “waiting rooms” then in operation, meaning the city was essentially using the locations as de-facto shelters. This is one of the conditions the settlement agreement sought to end.

“They have to stop using the waiting rooms as shelters,” Goldfein explained.

The current wait time for a new placement in the system is now much shorter, about 24 hours, City Hall says. Under the new settlement terms, some migrant drop-in centers will remain in operation, intended to serve those who reject other offers of shelter, arrive late at night, or request a temporary space to stay indoors.

Daniel Parra

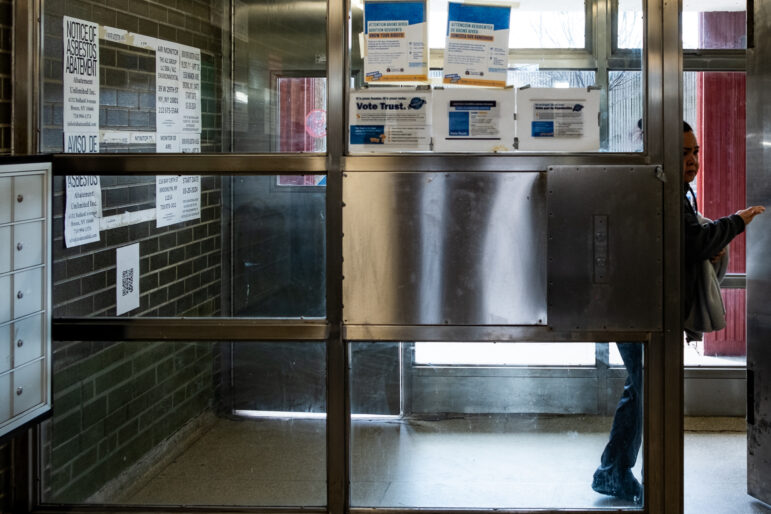

A line outside the reticketing center in the East Village, where migrants can request another shelter placement, on April 8.But the transition appears to be sowing confusion about the rules, at least at one drop-in center in Brooklyn. During the first two days under the new settlement that went into effect April 8, as City Limits reported, migrants who reapplied for a cot were sent to an “overnight hospitality center” at the Historic First Church of God in Crown Heights.

For two days, April 8 and 9, several migrants slept on the floor in the church. But the rules changed on April 11, according to people staying at the site. A video obtained by City Limits shows a shelter staffer telling migrants that night that they couldn’t sleep before 2:30 a.m.

“Just for the moment, the rules are changing, unfortunately, that’s what we were told today. We don’t know if it will be the same tomorrow,” the worker says in Spanish to a group of migrants seated at round tables in the church hall, according to the video. “Today the government said that you cannot sleep before 2:30 a.m.”

“The government?” One woman manages to ask before voices rise around the room.

At that moment, another staff member said in English, “If they want to leave, they are welcome to leave as well,” video obtained by City Limits shows.

“This is a ‘waiting room’ so you’re not outside,” the staffer said in Spanish later on in the video. “You’re not supposed to sleep, but we know you’re human beings and we let you lie down, but it’s illegal for us to do that.”

“I work tomorrow, what then?” a man in the video asks staffers shortly after.

When asked, the mayor’s office could not explain why staff told residents they could not sleep before 2:30 a.m., but said they do encourage people to stay in a chair and not lie on the floor. The reason, according to City Hall, is to avoid a fire hazard posed by people sprawled out on the ground.

“The health and safety of all migrants in our care is always a top priority. That is why those who choose to utilize our drop-in hospitality centers are asked to not sleep on the floor to avoid any risk of a fire hazard,” City Hall Spokesperson Kayla Mamelak said in a statement.

The mayor’s office said this is not a hard and fast rule, and that no one will be kicked out if they try to sleep on the floor. City Hall said staff at the Brooklyn church site are employed by MedRite, one of the companies contracted by the city to operate migrant shelters. MedRite referred questions to the city.

One person who stayed at the church drop-in site, who asked not to be identified for fear of retaliation, said that on the night the video was taken, workers did not let them sleep until after 2 a.m. “Anyone who fell asleep was woken up,” the 34-year-old Colombian said in Spanish.

Allowing asylum seekers and migrants to rest but not sleep is similar to the administration’s decision last year to prohibit homeless youth from sleeping at drop-in centers run by the Department of Youth and Community Development, according to Jamie Powlovich, executive director of the Coalition for Homeless Youth.

But City Hall said it has already sent out updated rules to the drop-in centers currently in use to prevent the bedtime misunderstanding from happening again. “We are communicating with staff on site to ensure that they have the proper information to relay to those staying overnight,” Mamelak added.

Dave Giffen, executive director at Coalition for the Homeless, said he thinks “there might be some issues with some of the drop-in centers not being clear about what they can and can’t do,” as the city continues to roll out the terms of the settlement.

“But we would hope that everybody acts with compassion and humanity and respect for the fact that these are individuals who’ve already been through a lot, and needed to be given a place to rest their heads,” he said.

“Staff are trying to do the best they can,” said Goldfein, “in a situation where the real solution is to help people get housing.”

With additional reporting by Jeanmarie Evelly.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Daniel@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.

2 thoughts on “City Advises Migrants to Sleep in Chairs at Overnight ‘Drop-In Centers’”

All illegal immigrants need to be deported. They come here illegally and make demands. How about going back to your own country and fight for your rights. The US owes them nothing, not free housing, free medical and our tax dollars. They don’t deserve to get anything over tax paying Americans. Send all of them back!

Not allowed to sleep until 2:30am, wakeup at 5:30? Sleep deprivation is a known form of torture.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sleep_deprivation