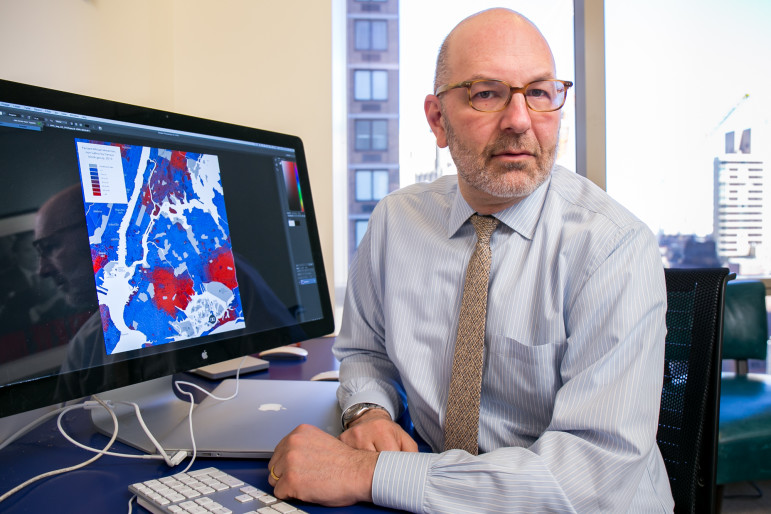

Adi Talwar

Attorney Craig Gurian at his office in Manhattan. His computer shows a map of racial concentration in New York City neighborhoods.

The building at 33 Eagle Street in Greenpoint is like many of the sites involved in Mayor de Blasio’s 10-year affordable housing plan. Subsidized through a combination of funding programs, it offers 97 apartments to be filled through a lottery, with applications due by May 16. If your income matches the targets listed for the property by the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, you can put in for a place there.

Some New Yorkers, however, will have a better chance than others of getting in.

Seven percent of the units are set aside for people with hearing, vision or mobility impairments, and there’s a preference for municipal employees in five percent of the apartments. But the best shot by far goes to those who live nearby, because fully half the slots are reserved for residents of Brooklyn Community District 2.

There have been city-subsidized affordable apartments on offer all over the city this year, from Ocean Hill III in Brooklyn to Van Cortlandt Green in the Bronx. They encompass different income mixes, building types and neighborhood locations, but they all share one feature: 50 percent of the units are reserved for people from the local community district. That practice of imposing a “community preference” has been around since Mayor Koch’s Ten-Year Housing Plan, and it increased from a 30 percent share to 50 percent under Mayor Bloomberg.

But a federal court could issue a preliminary ruling as early as this summer on a lawsuit that seeks to dismantle the community preference. Filed on behalf of three black New Yorkers who, the suit alleges, were locked out of affordable developments in mostly white districts because of the community preference, the lawsuit contends that what it calls the “outsider restriction policy” fosters segregation and constitutes illegal housing discrimination.

The lawsuit has ignited passionate argument—about the purpose and impact of the preference, and whether a realistic alternative exists. It comes at a time when the United States is confronting the legacy of past housing discrimination and as new research shows the disabling impact of residential segregation on peoples’ lives. The legal landscape is also tilting, with the Supreme Court last year permitting Fair Housing Act discrimination claims in cases where racial disparities are unintentional and new federal rules compelling local governments not just to avoid fostering segregation but to proactively work against it.

In the middle of it all, the mayor is trying to build 80,000 units of affordable housing, much of it via rezonings that some families and advocates fear will drive poor people out of the administration’s 15 targeted neighborhoods. Without a community preference to at least give those anxious neighbors a stake in the subsidized buildings, will de Blasio be able to get the local support he needs to redraw the city’s housing map?

The lawsuit against the community preference—or, as its foes call it, the “outsider restriction policy”—is the work of the Anti-Discrimination Center, founded and run by attorney Craig Gurian. In 2009, Gurian forced Westchester County into a $63 million settlement over claims that the county had falsely certified that it used federal funding to counter segregation. More recently, Gurian penned an op-ed faulting Democratic presidential candidate and Westchester resident Hillary Clinton for failing to address the county’s housing discrimination, and he was pictured in a New York Times story earlier this month about the intensifying debate over affordable housing and segregation.

Gurian’s case is built on the statistical fact that New York City, for all its melting pot mythology, is still a strictly segregated place. According to data cited in his court filings, in 2010 New York was the second-most segregated city in the country for both blacks and Latinos. That segregation is evident at the community board level: While the city is 23 percent black, 17 community districts have populations that are less than 5 percent black, while 11 districts are more than 50 percent black.

In that environment, the complaint argues, “this [community] preference serves to bar city residents living outside of the community district from competing on an equal basis for all available units. The result is that entrenched segregation is actively perpetuated, and access to the neighborhoods in this city with high quality schools, health care access, and employment opportunities; well-maintained parks and other amenities; and relatively low crime rates is effectively prioritized for white residents who already live there and limited for African-American and Latinos.”

Gurian declined to make his plaintiffs available for an interview, but according to his complaint they are black New Yorkers who applied via lottery for affordable apartments in Manhattan’s community boards 5, 6 and 7—which are, respectively, 64 percent, 72 percent and 69 percent white; blacks make up less than 7 percent of the population in any of those districts. That degree of segregation, Gurian notes, is itself the result of deliberately government policies like decisions on where to locate public housing, and he sees his lawsuit as trying to undo a policy that reinforces those older regimes of discrimination.

“It’s perpetuating segregation. It’s illegal. End of story,” Gurian,in an interview, said of the community preference. “What this relates to in terms of city policy throughout many administrations is the response to local desires to maintain segregation just the way it is and when you’re responding to that, that’s illegal, too.” The city should instead let any family who is income-eligible apply for any housing. Then, he says, “You would allow every building to be more reflective of what the city population is.”

Gurian paints this as more than just a narrow legal issue. Policing, education, health—”every single one of those things when you sort of strip it away and look at what’s behind it, it’s racial and ethnic segregation.”

In its court filings, the de Blasio administration argues that the affordable housing developments to which Gurian’s clients applied were covered by a community preference enshrined in state law, not the separate city policy. And the city says Gurian hasn’t shown that the community preference policy was created in response to racial animus or that it’s had any effect on worsening segregation or housing access citywide. (According to a 2015 story by DNAinfo, affordable housing lotteries in New York City draw on average of 843 applications per unit, which means that huge numbers of people are going to be turned away whether there’s a preference or not.)

The community preference policy, the city says, is “intended to ensure that local residents are able to remain in their neighborhoods as those neighborhoods are revitalized with affordable housing development.” It is also “a critical tool to ensuring that low income households, who are often disproportionately racial and ethnic minorities, are able to stay in the neighborhoods they wish to live in when investment results in rising housing and rental prices.”

A Bronx coalition last year surveyed residents who will be affected by the pending Jerome Avenue rezoning, it found that 43 percent wanted all new affordable housing built there to be reserved for local residents; another 33 percent wanted local dwellers to have a preference for 75 percent of the new units. Susanna Blankley, executive director of Community Action for Safe Apartments, one of the main players in that coalition, says those sentiments are not about a desire for racial purity but a fear of being uprooted.

“I think for us, folks are very concerned about being displaced, and they are also rent burdened and/or live in substandard housing,” she says. “So if something new is coming and it’s affordable, it should be for them. Why would we build for new folks coming in, when people in the community now need affordable housing?”

To Fred Freiberg, the executive director of the Fair Housing Justice Center, that argument doesn’t justify the community preference policy. “I have a problem with that because discrimination should never be an anti-displacement strategy. There’s other ways to deal with that issue.”

The de Blasio administration is trying some of those other ways, pushing to strengthen rent regulation and providing anti-eviction services. It’s working with the City Council on legislation to require a “certificate of no harassment” from property owners seeking building permits, aimed at discouraging landlords from trying to hassle tenants into moving out. There is pressure for the mayor to do more, including a push to create a right to provision of counsel in housing court, where low-income tenants often navigate eviction cases without expert advice.

Gurian’s legal case reflects a larger critique that the conversation about affordable housing has been dangerously myopic. Rather than trying to limit access to housing along community lines, he argues, advocates should be pressing for “solidarity across all kinds of boundaries” so that all neighborhoods welcome affordable housing and all affordable housing is open to people regardless of what neighborhood they’re from. (He points to a survey ADC conducted that found most black and Latino New Yorkers polled were willing to consider moving to a new borough or even outside the city.)”We really need to move to being that ‘one city,'” he says. “I know that won’t be easy.”

On that point, at least, affordable housing advocates agree with him: It won’t be easy. Many have raised their own questions about the focus of mayor’s housing plan on increasing density in low-income communities of color—just as they raised doubts about the Bloomberg administration tending to downzone white neighborhoods and upzone black and Latino ones.

But while there’s likely a political dimension to some of those decisions, there also are practical constraints on the city’s ability to distribute affordable housing evenly. Neighborhoods with really low density might not have the transit options to make substantial new development work. Building subsidized housing in neighborhoods with higher land prices means constructing fewer units within the city’s finite housing budget.

Hence the focus under de Blasio’s plan on places like East New York, Jerome Avenue and East Harlem. Each of those neighborhoods will see affordable housing built hand-in-hand with more market-rate development, which means residents can see a changed real-estate market and the secondary effects of higher rents and displacement.

While she says she shares the goal of a racially integrated city, Mutual Housing Association of New York executive director Ismene Speliotis doesn’t think the city has the resources to open new neighborhoods to those displaced from their homes. “You have to think that the people who are living there need to go somewhere else and so my dilemma is, ‘Where are those people supposed to go?’ because I don’t see the counter-balance,” she said at a recent conference hosted by the Association for Neighborhood Housing Development. “Because in the white neighborhoods, we’re not able, either zoning-wise or capital-investment-wise, building enough so that then we can ‘make salad.'”

John Reilly, a veteran of developing and operating affordable housing in the Bronx, sees the community preference as an acknowledgement of the practical impact affordable housing can have. “New construction can cause inconvenience, can change views, block sunlight, add to school and transit overcrowding,” Reilly, who runs Fordham Bedford Housing Corporation, says. “Acceptance grows when people realize they or their neighbors or friends may be able to move into a new unit.”

The growing need for senior housing, Reilly says, increases the need for a mechanism to keep people close to families, doctors and other means of support as they are. “These are real fair housing issues occurring every day,” he adds. “The efforts to relieve some of the housing pressures our residents face by providing new community sponsored affordable housing with a measured local preference are not [among them].”

Then, there are the politics. Whether it’s a single city-owned lot or a neighborhood-wide rezoning going through the land-review process, community boards and borough presidents shape and City Councilmembers and the mayor take the decisions that make new affordable housing possible.

In the recent debate over rezoning East New York, “the community’s main concern was neighborhood residents being displaced and not being part of the affordable housing built in the community,” says Councilman Rafael Espinal, who represents most of the rezoned area. Had there been no community preference, “I believe the whole deal would have taken a different turn. It would have been extremely difficult to push it through.”

If successful, the ADC lawsuit could change that calculus for the 14 neighborhoods whose rezonings are yet to come. For that reason, affordable housing developers and advocates are paying attention to U.S. District Judge Laura Taylor Swain’s rulings as the case moves toward a possible trial.

“There’s a lot of real anxiety about it,” says Rachel Fee, executive director of the New York State Housing Conference. “I think everybody’s watching.”

6 thoughts on “Advocates Wary of Lawsuit Over City’s Affordable Housing Preferences”

If the court rules against this totally appropriate preference then the whole ‘affordable’ housing scheme in NYC will fall apart because middle-class neighborhoods will want no part of it.

All New Yorkers pay for the tax breaks for this ‘affordable’ housing. We should get an equal crack at the lotteries.

While we disagree with a lot of the ‘social engineering’ behind the mayor’s plan, we think that the argument behind this lawsuit is spot-on.

You have a point but the political reality is that without the local preference ‘affordable’ housing will soon become low income housing. No councilperson from a middle-class district is going to want any of this in their district.

Pingback: Suit Against City Affordable Housing Policy Survives | City Limits

I seriously need an affordable unit but I feel like I have no shot at the lotteries because none of the new units, NONE OF THEM, are ever in my community board (#5). I was born and raised in Brooklyn and I’m still a resident. New housing keeps becoming available in neighbors that are near me but they aren’t my zone and it’s really unfair that I don’t have real chance of being considered for them.

I agree with you Angelica. I am in the same zone as you & have been applying for every lottery I see for over 4yrs now. None of the buildings in safe neighborhoods or outside community boards are contacting me. Some ppl (who fit income guidelines) wish to get out of bad neighborhoods & it seems like we will never win these lotteries bcz this system is not helpful.