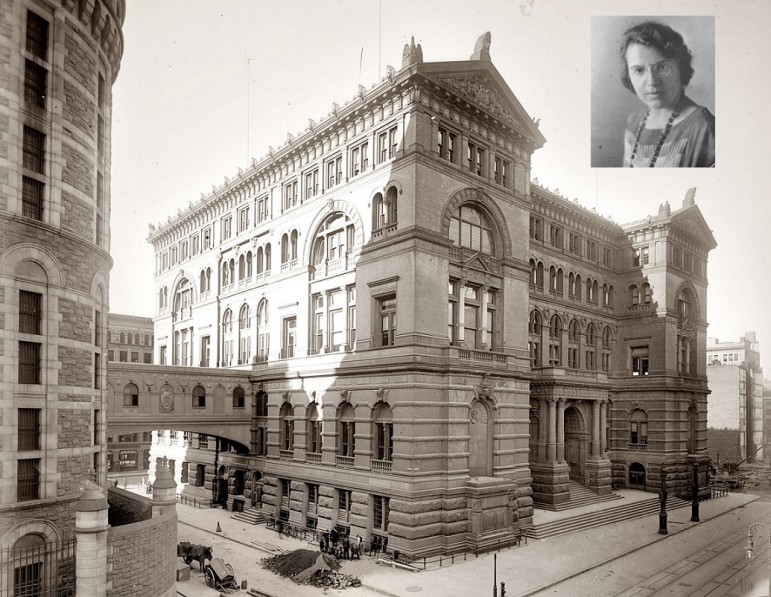

Photographer unknown

Anna M. Kross (inset) and the infamous Tombs Prison in downtown Manhattan, seen in 1907.

Today, if anyone knows the name Anna M. Kross, it is the inmates, uniformed correction officers, and mental health staff who live and work in the jail on Rikers Island named after her: The Anna M. Kross Center (AMKC), which houses the mental health center for the New York City Department of Correction (NYC DOC). But who was Anna M. Kross, and how did this center come to bear her name?

Who was Anna M. Kross?

Ms. Kross was an important figure in the history of correction and social service in New York City. As noted in the NYC Law Department newsletter, after graduating from NYU law school at age 19 (where Fiorello H. LaGuardia was a classmate), she had to wait to turn 21 to be eligible to take the bar exam. Ms. Kross then worked in the Family Court remembered to this day on the NYC Law Department website for being their first woman attorney leaving that position after 15 years to become the first woman magistrate in New York State, where she remained on the bench for 20 years. The Correction History Organization notes that Ms. Kross then became the second woman commissioner for the Department of Correction, holding this position for 12 years, longer than anyone else, male or female, up to the present time.

So why did the NYC DOC name the Rikers Island mental health facility after Ms. Kross? Because of her groundbreaking efforts at reform in this and so many areas of penology. She was known for standing up to authority, and her NYC Law Department bio states she “boldly criticized any faulty aspects of the system.” Even her obituary in The New York Times noted her “outspoken manner and independent ways.” Anna Kross championed the rights of women, adolescents, addicts and the mentally ill who were involved in the criminal justice system, and insisted that they could be better treated in other settings than jail or prison. The Historical Encyclopedia of Jewish Women notes that her reforms included “making the city’s prison system less dungeonlike and more humane… [installing] new shower rooms and mess halls… [building] separate facilities for adolescents … [and introducing] programs for rehabilitating prisoners” through academic and vocational training classes to provide education and—as Ms. Kross wrote about in the foreword to her own 12 Years of Progress Through Crisis, “skills required for entrance-level job placement in carefully chosen trades having labor market potential.”

Most of all, Ms. Kross “advocated for the implementation of psychological and psychiatric social work in the administration of criminal justice, and was instrumental in getting trained psychiatrists, vocational guidance workers, religious agencies and trained medical personnel involved,” as noted in her Five College online bio.

Beyond that, she was known for addressing some of the ills which continue to this day, working “on behalf of youth, advocating a more judicious attitude toward social problems… [insisting] that prison was inappropriate for the indigent, mentally ill, prostitutes, or those addicted to drugs or alcohol… [and speaking out] against the inequities of the bail system.” In Progress Through Crisis, Ms. Kross writes about how she established collaborative relationships with the New York City Board of Education, Department of Health, Department of Hospitals, Community Mental Health Board, Union Theological Seminary, the Council for Clinical Training, and the Hebrew Union College Jewish Institute of Religion for chaplaincy programs, with funding from the United States Office of Education, Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and the Manpower Development and Training Act, United States Department of Labor.

In her own words: “Fundamental to the development of any truly effective correctional treatment is the realization that correction itself is an integral part of the administration of justice. For too many prisoners it has become almost the reverse: the administration of injustice, the end of the line – a futile revolving-door type of operation which brings them back to institutional life over and over again, because a false sense of values and a fallacious economic reckoning have denied them a truly correctional experience. Particularly this is true in the case of the many innocent persons who are still held in detention pending trial only because they are too poor to furnish bail… to keep our overcrowded institutions of correction filled far beyond capacity with those who cannot be corrected through imprisonment, or with those whose only sin is poverty, is not only costly and nonsensical, it is downright immoral.”

Support for correction officers and staff

Ms. Kross also wrote about her focus on the need for training and supporting correctional staff, bringing psychiatrists from the NYC Department of Health and the NYC Community Mental Health Board to provide “expert help and advice in the classification and curative treatment of our prison population [and] training in lay counseling… to successive groups of Correction Officers.” She instituted new job prerequisites and requirements for correction officers, including “an academic minimum of a High School Diploma, plus a psychological examination and a police investigation… [creating] liaisons with schools of higher education, and [opening] the Correction Academy.” She celebrated that “our Correction Officers at long last have achieved complete parity in pay and pension rights with all other uniformed forces of New York City” and expressed her hope that “in the not too distant future all Correction Officers will be required to have this same graduate status, on a professional par with that of their Parole, Probation, and Social Work colleagues.”

Despite this impressive legacy, however, all of Ms. Kross’ good intentions to bring medical and mental health care treatment, education and justice to the impoverished, youth, addicts and the mentally ill in New York City correctional facilities have been seriously derailed for very long time. The Anna M. Kross Center (AMKC), which houses the NYC Department of Correction’s Mental Health Center, has done tremendous damage to the very people whose lives her professional career was devoted to helping. While Ms. Kross might be honored that the NYC DOC named this center in her honor, the stories that come out of AMKC would break her heart.

In September 2015, a correction officer was arrested for filing a false report regarding his action (or in-action) when he witnessed 53-year-old Victor in convulsions. Video shows that while other inmates tried to help, the CO did nothing until medical personnel arrived. Victor later died from a gastro-intestinal illness. One year before, in 2014, another CO (who had been disciplined for a similar infraction four years earlier) “left her post without permission as a mentally ill inmate lay dying in his 101-degree cell… basically baked to death,” due both to a malfunctioning heater, and the psychotropic medication that 56-year-old Jerome, a former marine who had become homeless, took to treat his bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Experts say these medications can make people more sensitive to the heat.

As reported only in internal State Commission of Correction (SCOC) Reports, in 2013, 45-year-old Carlos died of diabetes while being held in AMKC, despite medical records documenting his condition, and being observed by COs to display unbalanced gait and extreme vomiting. In 2012, Gregory died of suicidal hanging in AMKC, discovered dead in the bathroom where he ripped a prison jumpsuit and attached it to a fire sprinkler pipe. Gregory “received inadequate mental health treatment… inadequate inmate management, inadequate protection from harm and inadequate safety precautions…. [he] should never have been allowed to enter a private bathroom unescorted,” an investigation found. In 2009, 38-year-old David died from “a sudden cardiac event while experiencing severe agitation due to acute psychosis.” And in 2006, 43-year-old Devernon and 42-year-old John both died from asthma while in custody. Devernon’s report noted his medical care “lacked clinical con-tinuity, violated chronic care guidelines [and] lacked adequate monitoring,” while John’s stated the clinic schedule was routinely overbooked so that he did not receive care on a regular basis, nor was he transported timely to the hospital when he had a medical crisis.

How has this situation come to pass? Why are so many mentally ill people involved in the criminal jus-tice system and why aren’t they receiving better care? It started with the policy of de-institutionalization in the 1960s-80s, when public outcry against horrific conditions in large “snakepit” mental hospitals such as Willowbrook led to their closure. As a result, thousands of former psychiatric patients were released, with the promise of supportive housing and neighborhood mental-healthcare centers. When these never materialized, they became the army of homeless mentally ill seen throughout the streets of the city. Together with drug abusers and alcoholics who could not find beds in overcrowded treatment centers, and juvenile delinquents who were not diverted to appropriate youth detention centers, they often find themselves incarcerated and wind up on Rikers Island.

More support needed for the severely mentally ill

Despite Mayor DeBlasio’s recent attempts to address mental health and wellness for the general public in New York City, there is almost nothing in the new ThriveNYC plan that deals with treatment for the severely mentally ill. This program attempts to address mental illness by providing a “roadmap” to help connect all New Yorkers to mental health services, offering support for those experiencing various forms of situational depression, i.e., postpartum depression, stress arising from unemployment, homelessness, being widowed, going through a divorce, teenage peer pressure, and drug/alcohol abuse. However, services for the chronic mentally ill – who make up over half of the population at Rikers – are minimal. D.J. Jaffe’s article “Sadness isn’t the problem,” published in City Journal, notes that despite DeBlasio’s good intentions of taking a “public-health approach to mental illness [by] examining… root causes” and providing preventive care such as social and emotional education for school children and supportive visits for the elderly, ThriveNYC does not address treatment for “schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, the two mental illnesses frequently found in the homeless, hospitalized, incarcerated and violent … [these] serious mental illnesses can’t be prevented because their causes are not known.”

ThriveNYC does discuss the (as Jaffe noted, “previously announced [but] still unimplemented”) NYCSafe program, “designed to support the narrow population of New Yorkers with more complicated mental illness who pose a concern for violent behavior.” This program promises to provide crisis intervention teams to “reduce violence and address treatment in the city’s jails,” with mental health care units and additional mental health training for correction officers, specialized care for adolescents, expanded substance abuse treatment and reducing inmate to staff ratio (at least for youth). Discharge planning services are also addressed in Thrive, as are supervised release studies and supportive housing. Clearly, it is not sufficient to devote less than 8 pages out of the 118-page ThriveNYC program to the severely mentally ill, and nowhere does it address the issue identified by police chief Bratton in Jaffe’s article in City Journal, that there are not enough beds or facilities that can retain and treat this population.

Indeed, the mentally ill, addicts and juvenile delinquents – those “unfortunates who cannot quite steer clear of the law,” as Anna Kross put it, whom she strove to have removed from prison to facilities better equipped to serve them, continue to be underserved. When the large public institutions were closed with no small community services in place to provide the needed services to this “narrow population,” they are once again being held behind bars… together with dangerous, violent, repeat offenders… and those just awaiting trial who cannot make bail. These different populations need to be screened and separated before they come under the custody and control of correction officers.

Reform is desperately needed

Indeed, if Anna herself were able to respond to these events, we could feel her shuddering in her grave at these stories, so strongly that it shakes the earth. One can only hope that her spirit of reform, and awareness that so many people who are incarcerated in our correctional system would be much better served in other institutions – and that those who do need to remain locked up would improve and be able to re-enter society as productive citizens, rather than return to prison through the revolving door of recidivism – if we just treat them with dignity and provide the services they need to move forward. Let those in power today remember Ms. Kross’ lessons and leadership from the past, and provide adequate education, mental health care, and social services for those in the criminal justice system. We must abandon this history of violence against those most vulnerable members of our society, and the all-too-frequent abuse, beatings, belittling, suicide and murder of those who are locked up – especially those who are held in the building with her name above the door.

Despite even the Attorney General for the United States writing poignant and pointed reports about the deplorable conditions on Rikers Island, nothing is happening to close this hellhole. Will it take an Attica-style uprising, resulting in the deaths of multiple officers and inmates, to make a difference? Or can we resolve to remedy this situation before such a tragedy occurs?

Let us hope we can follow the example of Anna M. Kross, and pursue progress through crisis.