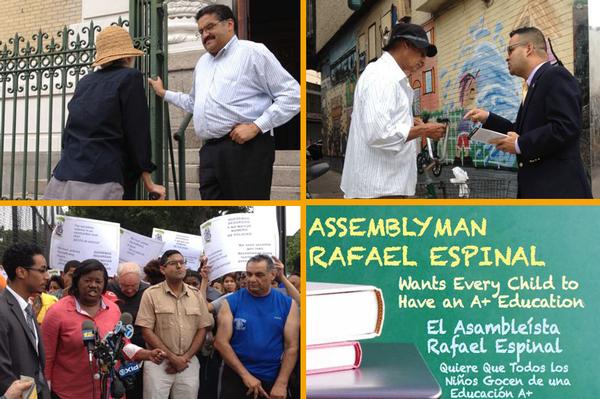

Photo by: Tobias Salinger

Images of the District 37 race, clockwise from top left: Mike Nieves, who dropped out; candidate Helal Sheikh talks to a voter; a mailing by pro-business PAC Jobs for New York showcases its support for Assemblyman Rafael Espinal; and Candidate Kimberly Council at a press conference about gun violence in Bushwick.

As he shuttled between three churches in a beat-up Toyota SUV last week campaigning for a central Brooklyn City Council seat, veteran political operative Mike Nieves pointed to a summons from the city Board of Elections among a stack of campaign flyers, a half-eaten candy bar and an empty ice tea can in the backseat. The board wanted Nieves to answer a challenge to the signatures he’d submitted to qualify for the primary ballot—a challenge mounted by his opponent, Assemblyman Rafael Espinal.

“If I’m going to combat that, I’m going to have to spend my own money. I don’t have a Jobs for New York behind me,” said Nieves at the time.

Two days later, his campaign announced he was dropping out of the race.

Nieves had been one of five candidates trying to replace the term-limited Erik Martin Dilan in Brooklyn in a race marked by an infusion of cash from Jobs for New York, the new pro-business PAC started by the Real Estate Board of New York and construction worker unions.

Mailings supportive of Espinal’s effort to replace his former boss (he used to be Dilan’s chief of staff) paid for by Jobs for New York have candidates and observers wondering if an onslaught by the committee will turn the race decisively for the first-term lawmaker—and, in turn, affect city housing policy. It’s a dynamic that could alter how campaigns are run and make donations to candidates themselves less meaningful.

“Some voters tend to pay greater attention to direct contributions than they do independent expenditures,” says Gene Russianoff, senior attorney for the New York Public Interest Research Group. “We’re going to find out for the first time in city elections what difference they make in electing a candidate.”

PACing a punch?

Nieves ended his campaign after he said the roughly $23,000 he raised dried up in lawyer fees associated with the signature challenge.

The remaining field for the seat representing parts of Bushwick, East New York, Cypress Hills and Bed-Stuy—which census data shows is 56 percent Latino and 30 percent African-American—includes neighborhood church leader Kimberly Council, city Commission on Human Rights staffer Heriberto Mateo and former high school math teacher Helal Sheikh.

While the latest filings with the city Campaign Finance Board show Espinal has only raised about $2,000 more than Council, his nearest competitor, that $57,946 direct mail expenditure by Jobs for New York on his behalf may already be turning the race in his favor.

“To have that money spent early on direct mail is significant because there are many City Council candidates who don’t spend that much on it through their own campaigns,” says Gerry O’Brien of Gerry O’Brien Political Consulting, who is not working for any of the candidates. City campaign finance laws limit campaign spending by Council candidates to $168,000 if they elect to accept public matching funds. But independent committees can spend unlimited amounts, thanks to the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision.

The eight flyers in Spanish and English are just the beginning of the committee’s efforts in the election, observers say. Espinal, 29, who was elected to the Assembly in 2011 from a district which covers much of the 37th council district, has picked up support both from Councilman Dilan and state Senator Martin Malavé Dilan, the councilman’s father, along with unions like the United Federation of Teachers and the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association.

Espinal says he welcomes the backing from Jobs for New York. “I’m very grateful for their endorsement,” says Espinal. “They do believe that I’m the best candidate to create jobs and to do the job in the City Council.”

But Espinal’s opponents argue that such enthusiasm is troubling in itself. Council, 41, a law librarian at Sullivan & Cromwell LLP who is also vice president of the East New York Housing Development Corporation, has taken in the largest number of donations. She says she she’ll be reporting a contribution from U.S. Rep. Nydia Velázquez in the next cycle, but she’s already gotten $300 from the Brooklyn pol who gave Velázquez her start: former Rep. Edolphus Towns. Her maximum $2,750 donations come from 1199 SEIU and former state senate counsel Maggie Williams, along with the PAC she co-chairs, New Yorkers for Social Justice. But Council, the recipient of endorsements by the Working Families Party and the Council Progressive Caucus, complains of an “undue influence” on the race by the new real-estate PAC.

“They’re not doing it out of the goodness of their hearts,” Council says. “They’re doing it because they expect something in return.”

Jobs for New York operative Phil Singer wrote in an email statement that Espinal got the group’s backing because he stood out from other candidates in the 37th district.

“We spent a lot of time researching the candidates in this race and believe Assemblyman Espinal is not only the most committed but the most capable when it comes to creating jobs and opportunities for middle-class New Yorkers,” Singer wrote.

The $5.2 million in contributions disclosed by Jobs for New York in a July 15 report went to set of incumbents like Harlem Councilwoman Inez Dickens and Councilwoman Margaret Chin from Lower Manhattan, as well as strong challengers for open seats like Staten Island’s Steven Matteo, the former chief of staff to outgoing Councilman James Oddo. The group lists eight endorsements on its website, but other accounts say it could participate in as many as 25 races. (Brooklyn Bureau last week wrote about another Council race in which Jobs for New York is a factor, in Fort Greene.)

Housing looms large

Housing and development loom large in a district buffeted by gentrification. Father John Powis, a politically outspoken retired Bushwick priest who sits on the board of the Bushwick Housing Independence Project, says developers want longtime residents to step aside for new higher-priced buildings.

“It moved fast in Williamsburg but it’s moving even faster in Bushwick,” says Powis. “They’re displacing so many people.”

Council notes that she’s helped build 300 affordable units in East New York through the development corporation, and points to her work in creating a new building at the Berean Baptist Church. She says if she is elected she will push to increase the ratio of affordable units subject to tax-exempt bonds in new buildings from 20 percent up to 25 or 30 percent.

“We have to look at what people are making and what we are asking people to pay because people are being priced out of their neighborhood,” says Council.

Even Helal Sheikh, 39, an energetic newcomer to city politics vying to become the first Southeast Asian elected to the Council, attempts to introduce himself to area voters by invoking ire against those in power as he shakes hands at a subway station.

“We need something to change,” he says to a voter who stops for a placard outside the JMZ line on Broadway. “We need new people to run, not the same ones again and again.”

The former teacher in a now-closed high school, who is at least partially fluent in five languages, immigrated to New York from Bangladesh when he was 17. He somewhat vaguely pledges to do what his constituents tell him to do if he were elected. “Whatever their priority, I will work on it,” says Sheikh. “And I’ll find out what they need.”

Heriberto Mateo, who was a close runner-up to Erik Dilan in the 2001 Council election, did not return requests for comment.

Espinal says campaign money doesn’t determine his decisions as a lawmaker. And he said he would try to lower rents if he is elected to the Council.

“Property taxes do have an effect on how homeowners price the rent,” Espinal says. “I’d like to find a way to lower those taxes so that homeowners can provide housing for less.”

Debate approaching

In the Cypress Hills section of the district, where Powis says there are people “living in the basement of shops in the most horrendous conditions,” the candidates will participate in a forum on housing, public safety and education on Aug. 14.

The Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation is hosting the forum in concert with 10 local churches and community groups. The nonprofit housing, health and education agency joined the city-wide “Our City Our Homes 2013” coalition calling for greater code enforcement, affordability mandates in new developments, public housing preservation and foreclosure prevention.

“The current housing crisis is not just the result of challenging or speculative market forces, it is also the consequence of our city’s failure to build the housing we need and to adequately preserve the affordable rent regulated, subsidized and public housing that we already have,” reads the coalition’s platform.