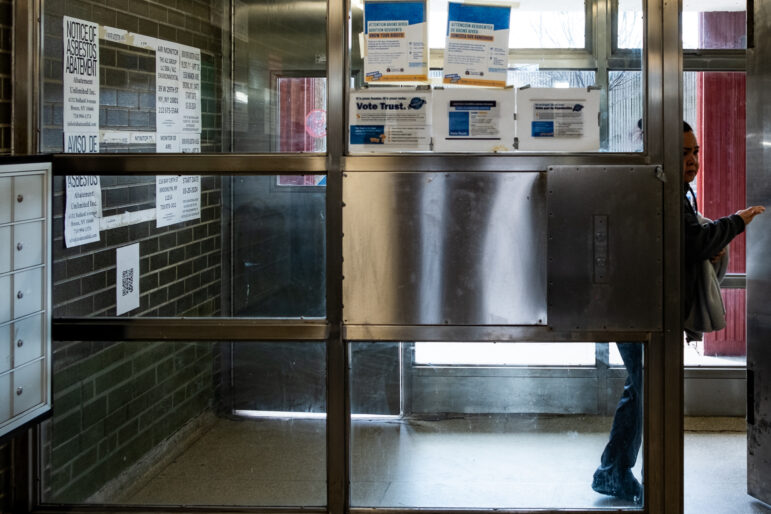

Adi Talwar

A part-time worker at a local CVS says he's not given enough time to do his job properly, let alone earn a decent wage.

The problem of low-wages in New York City and across the U.S. is, in some ways, not about wages at all. It’s also about hours—or the lack thereof. A 2012 study of more than 400 retail workers by the Retail Action Project found that only 17 percent had a regular schedule.

As part of its investigation into who profits from low wages, City Limits spoke with a clothing store manager who said labor costs amount to 15-20 percent of his overall expenses. He estimates that his store increases its profit margin by 5-15 percent by having mostly part-time workers, who are paid $10 per hour and don’t receive health or retirement benefits from the company. To change the part-time structure while still making a profit, he says, “we would have to make cheaper clothes.”

It’s an argument commonly deployed in opposition to increasing the minimum wage, which currently stands at $8.75 an hour in New York. Some think-tanks – like the fiscally conservative Employment Policies Institute – claim that the cost of increasing wages drives employers to lay off workers or slow down hiring to maintain profit margins and product quality.

Cutting employee benefits by staffing mostly part-time workers has a similar effect. Companies save money up front by lowering the amount they spend on employees’ insurance and retirement benefits, but some economists, including the Fiscal Policy Institute’s James Parrott, argue that business owners get a bad deal too.

Jerome Murray, a part-time worker at a local CVS, sees evidence of the downsides of part-time work on his own shifts. He says his primary role is as the store’s Hallmark merchandiser, arranging and stocking the cards. He’s given four hours per week on that section, for a job he says would take 16 to 20 “to keep the section running.”

He’s palpably frustrated by not having the time he needs to do his job right; Jerome takes pride in his work. “The store looks like garbage,” he says. “The section is a mess, there’s not enough cards there.”

The clothing store manager said only 20 percent of his staff is full-time. Full-time, in this case, means working 32 hours per week at $10 an hour. The manager said most of his workers are students because they tend to be able to change their hours with fewer problems. “We like the flexibility of having a student workforce,” he noted.

But the manager knows that several of his part-time staff members live in homeless shelters, unable to afford apartments in the city. “If they’re working 25 hours at $10 an hour, they can’t afford $500 a month just in rent,” he said.

Reporting for this story was generously supported by the Puffin Foundation.

One thought on “Low-Wage Problem Also a Low-Hours Problem”

Pingback: Sanford Heisler Kimpel LLPThe Fight For $15 and a Fair Schedules - Sanford Heisler Kimpel LLP