Photo by: Dliif

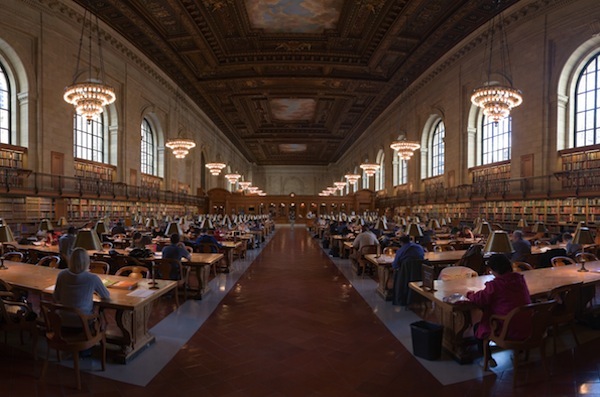

As repositories of information available to anyone who walks through the door, libraries have always helped foster transparency, accountability and democracy. Their boards, however, struggle on all three counts.

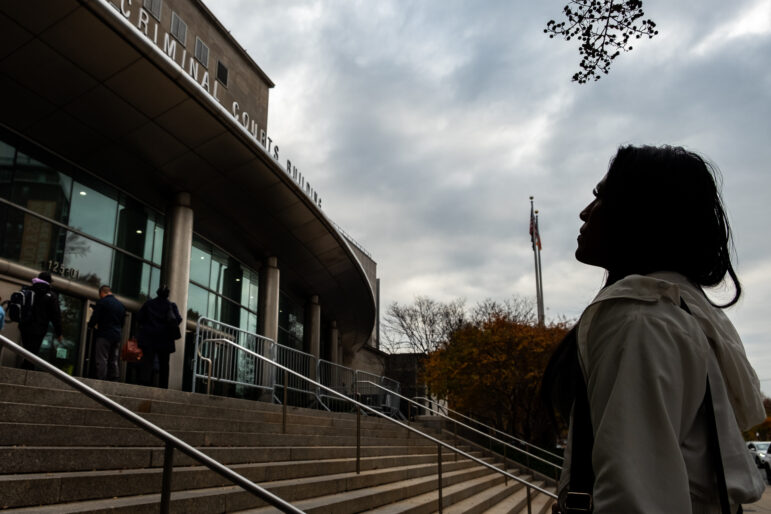

A princess sits on the New York Public Library’s board of trustees, but no one from Staten Island does, despite the library’s 13 branches in the borough.

Her Royal Highness Princess Firyal of Jordan, a philanthropist, socialite, and UNESCO Goodwill ambassador, is one of nearly 100 trustees on the boards of the New York, Queens and Brooklyn Public libraries, which are non-profit institutions funded largely by the city.

These boards are responsible for oversight of more than 200 branches and hundreds of millions of city dollars. In an era of tight budgets and record library usage, what trustees decide about renovations, capital projects, programming and staff matters for everyday users.

Over the last year, library trustees have seen more of the spotlight than usual because of moves that put boards at odds with public opinion: NYPL’s now-abandoned plan to insert a circulating library in place of the stacks at its iconic building on 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue, Brooklyn Public Library’s still-active effort to sell its Brooklyn Heights branch to private developers, and the Queen’s Public Library board’s split vote on whether to require library chief Thomas Galante to take a leave of absence given city and federal investigations into library construction projects and contracts.

These disputes have exposed weak points in the public-private hybrid structure of the libraries, where the non-profit status of boards limits outside oversight and access to information even as the libraries press for more public funding after years of cuts. At a time of growing income inequality, the role of trustees who can give or raise private money to support the libraries also prompts more fundamental questions: How representative of the city are the library boards? Whose interests do they represent?

As repositories of information available to anyone who walks through the door, libraries have always helped foster transparency, accountability and democracy. Their boards, however, struggle on all three counts.

Little public information

Finding out who sits on the library boards isn’t difficult — each library posts a list of trustees on its website and keeps it relatively up to date. But learning more about the person behind each name can be challenging. None of the libraries include trustees’ bios on their websites, and none provided them when asked to for this story. And that old reporter’s standby, actually talking to someone in person, only goes so far.

When asked for basic biographical information — age, profession, neighborhood, years on the board — following a meeting last month, four Queens trustees declined to answer or provide a phone number for a later interview. “I don’t think I’m going to do that,” said trustee William Jefferson. The others — Grace Lawrence, Patricia Flynn and Terri C. Mangino — simply said “no.”

As in Queens, NYPL trustees don’t seem eager for scrutiny. After suggesting that I forgo the “schlep” in for what promised to be a “boring” meeting of the Trustees’ Capital Committee in January, an NYPL spokesman asked me outright not to attend because “having a reporter in the room makes some people nervous.”

Members of the public rarely sat in on Brooklyn library board meetings until the controversial plans to sell branches emerged; before Galante came under fire this year, the Queens board operated in similar obscurity. Matt Gorton, a member of the Queens board since 2008, says, “We always knew the meetings were public meetings, but I don’t remember anyone ever showing up.”

Perhaps that’s because the public can’t speak at them. Members of the public can listen at board meetings but formal communication with the board is limited to letter-writing.

The public is entitled to receive meeting minutes—though in 2012, the Queens library denied copies of minutes to a group of union officials who requested them until a state Supreme Court judge required the library to make them available. As non-profits, the boards must file 990 tax filings, a starting point for transparency with its lists of trustees, top executive salaries, and overall revenues and expenses. The boards are subject to the state’s Open Meetings Law but typically not New York’s Freedom of Information Law.

Different structures

Each board operates under very different structures, outlined in bylaws and state legislation. In Queens, the mayor and borough president make alternate appointments to the 19-member board, which includes one appointee from each of Queens’ 14 community boards.

NYPL’s trustees are selected by a trustees’ nominating committee and elected (and re-elected) by the board itself. Members are not required to live in New York City. Trustees—currently 39, but as many as 44 – are chosen with an eye to expertise that can help the library, but because NYPL must raise its own money to support its four major research libraries, deep pockets are welcome.

Brooklyn’s 38-member board operates in a middle ground: The mayor and borough president appoint the majority of trustees, but the board itself elects a dozen board members who can match concern for the library with fundraising abilities. New York and Brooklyn trustees serve three-year terms; in Queens, the terms are five years. Re-election and re-appointments are common .

NYPL suggested Googling its trustees, and the prominence of its members does make it easy to identify them with an online search (though finding them all takes a while). Harder to discover is how long each member has been on the board, or how much of what’s online is accurate. Brooklyn’s members also have a substantial Internet presence, but information about their appointments or election is also scarce.

Getting to know the Queens board is more difficult. Many members are well known in the borough through their businesses, involvement with a community board, or role in city government, but the traces they have left — at least online — don’t lend themselves to anything like a complete or accurate bio.

When asked for that information during a trustees’ meeting break, library spokeswoman Joanne King was able to provide basic, off the cuff identification for about half the trustees. Even some on the board have only a vague sense of their fellow members’ backgrounds and ties.

Fundraising skills are a must

Spokesman Ken Weine notes that NYPL’s board composition reflects its trustees’ hefty fundraising role — they raise $90 million a year to support its four research libraries and $955 million endowment — thereby accounting for the significant mix of philanthropists, socialites and financiers.

The 42nd Street landmark building was renamed for trustee Stephen A. Schwarzman, the billionaire CEO and co-founder of private equity firm Blackstone, after he gave the library $100 million in 2007. But cultural heavyweights on the board like opera singer Jessye Norman and New Yorker editor David Remnick give the impression of diversity and balance.

The board members often have relationships with one another that go beyond their shared commitment to the NYPL.

The library’s 39 current board members include two trustees who have appeared on Vanity Fair’s International Best Dressed List. Two are partners in the same hedge fund. Two — one as buyer, one as seller — exchanged ownership of a $37-million, 34 room Park Avenue apartment. Two eminent scholars on the board (Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and the newly-elected Kwame Anthony Appiah, both of whose expertise on Africans, African-Americans and the African diaspora is vital to a library that includes the Schomburg Center for Research on Black Culture) have written or edited several books together. Appiah’s personal website notes that his partner is editorial director at Remnick’s New Yorker and that Gates was witness at their 2011 wedding.

Connections run through the boroughs and across library systems. In Brooklyn, BPL trustees Hank Gutman and Peter Ashkenasy both also hold seats on the Brooklyn Bridge Park board. Gutman is a partner at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, where Schwarzman’s Blackstone Group is a major client. David Offensend, who has been Chief Operating Officer for the New York Public Library, is also on the Brooklyn Bridge Park board; before joining the library, he founded private equity firm Evercore Partners with the former vice-chairman of Blackstone. Queens board member Haeda Mihaltses’s husband George is NYPL’s vice president for government and community affairs.

Although the New York Public Library board includes three ex-officio trustee seats for citywide officeholders— the mayor, City Council speaker, and comptroller, who typically send delegates rather than show up themselves—the legislation governing the board created no posts for the borough presidents of Manhattan, the Bronx and Staten Island, where the library operates 88 neighborhood branches, possibly to avoid pitting the boroughs against each other in a close vote.

The board has a few trustees with ties to the Bronx; Staten Island, population 472,000, has nobody.

Looking to fill gaps

NYPL President Anthony Marx, who championed the cause of socioeconomic diversity in his previous gig as president of Amherst College and was hired by the NYPL trustees in 2011, says looking at the board’s composition is “absolutely fair game.”

When selecting potential trustees, Marx explains, the board’s nominating committee reviews a matrix of the board’s overall makeup, looking at the age, experience, and other attributes of existing trustees, maps those traits against the library’s identified needs for expertise (and presumably fundraising power) and tries to find new members who can fill in the gaps.

Along with Appiah, the scholar and NYU professor, it recently appointed Beth Kojima, a partner at hedge fund TPG-Axon, for her investment and technology experience and ABC anchor George Stephanopolous for his media and government relations experience, Marx says.

“We have noticed we don’t have anyone from Staten Island,” Marx said in a recent phone interview. “Any suggestions?” he adds.

But, he notes, “In the last 12 months, we’ve opened a new branch on Staten Island, and done a major renovation, and we’re working on a third one. That’s actually more branch investment per capita in Staten Island than elsewhere. So the argument that they’re getting short shrift — I’m not sure I can accept that.”

At the December grand opening of that new branch, in Mariner’s Harbor, resident Clara Sue Ogburn noted that 70 years had passed since her parents and grandparents moved to the neighborhood and, as members of the Arlington Civic Association, began pushing for a branch to be built there. “People in power were not focused on it,” she said at the opening.

“Naturally it would be a problem for Staten Islanders that we don’t have any kind of representation on the [NYPL] board,” she said in a recent phone interview. “Is Staten Island going to be left out again because no one knows what the needs and concerns are?”

She added: “It’s not that you don’t appreciate those of means being on there — that’s a necessity — but any time you’re dealing with a board, a good board member knows how to relate to anybody of any socioeconomic level. A good board shows that.”

Queens board under fire

With its appointees from the mayor and borough president and relatively minimal fundraising duties, the Queens trustees have a mix of experience in city government, Queens businesses and local non-profits.

Chairman Gabriel Taussig is former chief of the city’s law division; Ed Sadowsky is a former city councilman. George Stamatiades is a funeral director, president of the Central Astoria Business District and has sat on Community Board 1 for some 30 years. Mary Ann Mattone has worked for real estate company and major developer The Mattone Group, which was founded by her husband, Joseph.

One of the newest trustees on the Queens board is Maria Concolino, a Bloomberg appointee and one of the few on any of the city’s library boards whose main credential is community-level activism.

A decade ago she became president of the Friends of the Woodhaven Library, after determining that “we weren’t getting our fair share of programs and that no renovations were being done.” She got to know elected officials and library staff as the renovation went from plans to completion last year. Her branch experience has made her a skeptic of information delivered by library executives; she’s seen librarians reluctant to be forthright for fear of losing their jobs, and has long been suspicious of how the library allocates and manages capital funds. (She voted for Galante to take a leave of absence.)

Gorton, also a Bloomberg appointee who worked in City Hall and recently joined a PR firm, says Concolino’s perspective is valuable because it is “probably closest to the people who actually come to the library.”

“We’re talking about lawyers, but she’s saying ‘What about that handicapped accessible ramp at the branch that’s broken?’ She brings us out: ‘Let’s get out of this board room and remember we have 62 branches and we should be thinking about this,'” Gorton says. “I can’t speak for other board members but for me it’s a reality check.”

For all its geographic diversity, the board seems unrepresentative of Queens in some respects. People who identified their race as “Asian alone” make up a quarter of the borough’s population and own nearly a third of its businesses, according to census figures, but they hold no library board seats. In a borough where nearly 50 percent of residents were born outside the United States, immigrants have a much smaller presence on the board (Taussig immigrated from Israel as a child).

For now, though, the Queens board is under attack not for how representative it is of different identity groups, but for how it has done—or failed to do—its job: oversight of the library’s management and finances. An April 6 Daily News editorial criticized the entire board for “horrible judgement” for authorizing Galante’s $392,000 salary and allowing him to work over 20 hours a week as a consultant for a Long Island school district, and called for the ouster of the nine trustees who voted not to put the library chief on leave while he and the library’s finances are under investigation.

Next week, the library will be in state Supreme Court to face City Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office over the library’s refusal to turn over financial records the library claims are outside the Comptroller’s audit authority—those pertaining to private donations, grants, and state and federal funds.

Galante’s salary (Mayor Bill de Blasio makes $225,000,) along with his full-time use of a $37,000 library-owned car, prompted outrage in part for seeming incongruous with the budget picture for the library’s branches, where hours were reduced and staff reduced through attrition and layoffs as the city cut library budgets by some 16 percent from 2009 to 2013. In 2011, the Queens library bought no books for six months.

BPL President Linda Johnson earned some $280,000 in base pay in 2013, according to the library’s 990 filing. NYPL president Marx earned $781,000 in total compensation last year, says its 990 filing. Marx’s salary is paid by private funds. Operating from two pots of money—public and private—is useful for the libraries, allowing NYPL to hire leaders who could draw big salaries as heads of universities or other non-profits. Queens, which has a full-time spokesperson, recently authorized the use of $30,000 in “private money” to hire a publicist in the hope of generating good press.

State lawmakers have proposed several bills aimed at reforming the Queens Library board by creating an audit committee to oversee the library’s accounting and financial reporting processes and annual audits, requiring key library staff to file financial disclosure forms and shortening board terms from five years to two, among other measures.

The Queens trustees themselves, who all agree care deeply about the library, are also taking steps toward reform, with plans to hold an off-site discussion on governance, board and committee restructuring that would be led by someone knowledgeable in best practices for non-profit boards. But change of a different sort seems likely for the Queens board: New Borough President Melinda Katz has vowed to replace the current borough president appointees as their terms expire.

Call for new names in Brooklyn

The hybrid model of Brooklyn Public Library’s board—which combines mayoral and BP appointees along with members elected by the board itself—came about in 2007 when the library revamped its board structure through state legislation; previously the board included only trustees appointed by the mayor and borough, while a separate foundation board existed as a fundraising arm.

“You had a dynamic where the people who were involved in fundraising were not otherwise involved in the library,” says Brooklyn Public Library executive vice president David Woloch.

(Queens currently employs this set-up, though several people sit on both the QPL trustees and foundation boards.)

Since the restructuring the ability to give or raise money is an important attribute for elected members, Woloch says, but every trustee has the same role. Brooklyn’s board includes members with legal, financial, public affairs and city government experience, with a sprinkling of writers, a school principal, and a former president of the New York Library Association.

In part to make up for reductions in city dollars for the libraries, the board has increased fundraising by 100 percent in the last year. An ex-officio board seat was added for the City Council speaker in the Brooklyn overhaul as well, “which was important because we rely so much on the Council for funding”, says trustee Anthony Crowell, Dean and President of New York Law School.

Critics (including Citizens Defending Libraries, and others) of the Brooklyn board’s plans to sell at least one branch to private developers, which the library says is necessary to raise capital for renovations and repairs throughout the system, say trustees appointed by Bloomberg and former Brooklyn borough president Marty Markowitz represent corporate and development interests over the interests of community members.

“We find virtually no one on the street who’s in favor of these library sales and shrinkages,” says Michael D.D. White, co-founder of Citizens Defending Libraries, which launched campaigns to oppose the NYPL’s Central Library Plan and Brooklyn’s Pacific Street and Brooklyn Heights branch sales.

In testimony at a city council hearing on the libraries’ budgets this month, State Senator Velmanette Montgomery said the new mayor and borough president should appoint trustees who “better reflect what the public expects of its library system,” proposing 11 names for consideration, including former NYC school s chancellor Rudy Crew, Pulitzer-prize winning playwright Lynn Nottage, and S.J. Avery, a trustee of the Park Slope Civic Council, which worked to halt, at least for now, the library’s plan to sell the Pacific Street branch and relocate it in a high-rise development adjacent to the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Crowell says the board is “exceptionally representative of Brooklyn, and has people with very longstanding commitments and roots in the borough…from a broad range of professional backgrounds.” He dismisses the assertion that ties to developers are driving trustee decisions about branch sales, and adds that as long as no direct conflict of interest exists for trustees — meaning they don’t stand to benefit financially or don’t work for a firm involved in a library deal, “I don’t think it matters.”

Branching out

Knowledge of the branches, the needs and perspectives of users, the challenges facing staff — these concerns lie at the heart of questions about whether and how trustees represent New Yorkers.

Brooklyn used to hold meetings in the branches, but hasn’t for years, Crowell says. The Queens board has discussed holding a trustee meeting at a branch library, but to date has not. The NYPL trustees full board has “a tradition” of occasional meetings in branches; last fall they met at the Countee Cullen branch in Harlem, says Weine. Some trustees have done more: New educational programs emerged from a trustees committee that toured branches and talked with users and staff, says NYPL vice-chairman Abby Milstein. Marx says trustees are for the first time raising private funds for those programs in the branches.

Woloch says it’s a challenge for Brooklyn board members with fulltime jobs and other responsibilities to stay in touch with what’s going on in the branches. In the past year, the library has begun taking small groups of trustees on branch visits; on one, they visited the large and recently updated Kings Highway branch and the cramped and ailing Carnegie building at Eastern Parkway.

“You have 60 locations delivering on paper similar services, but each one is different and there’s a different dynamic — each librarian runs it a little differently and each is shaped differently and neighborhoods use them differently,” Woloch says. “The board approves our budget, and I think it’s extremely important for them to recognize what’s happening in the field.”

What, exactly, does democracy look like?

New York’s public library systems owe their founding to wealthy people with democratic ideals. They hoped to make knowledge available to all and to strengthen democracy through an educated citizenry.

But some branches that are now part of the Queens, Brooklyn and New York systems—Roosevelt Island, Paerdegat, Langston Hughes among them—also owe their founding to community groups and civic associations who started their own neighborhood lending libraries which were later folded into the larger systems.

Library trustees throughout the systems still profess commitment to the values of democratizing information and promoting lifelong learning. NYPL’s maligned Central Library Plan was supported by trustees in part because they believed it would further the library’s democratic mission by combining a circulating branch—with its implied use by everyday patrons—and a research library cherished by scholars in a beautiful building open to all. Could the library have been spared a costly, time-consuming, and seemingly painful process by a more diverse or representative board?

Whatever the answer, lawmakers and members of the public are now using tools of the democratic process -legislation, petitions, public testimony—in attempts to make the library boards themselves more democratic.

In testimony before a City Council sub-committee on libraries several days before the NYPL reversed course on its plans for the 42nd Street building, Charles D. Warren, architect and co-author of a book about Carrère & Hastings, the men who designed the landmark building, called for transparency and an open process in the NYPL board’s decisions about that plan—and for Council members to weigh in on the appointment of ex-officio trustees to be named by the new City Council speaker, mayor and comptroller.

“I urge you to make sure that this time there are three people appointed with a backbone, with a knowledge of the library, with an interest of representing our interests on those boards, and with the possibility of reporting back to us what’s going on on those boards when they’re so often having meetings that are behind closed doors in executive sessions,” he told them. “You all—that’s in your power.”

This story is part of a series looking at the potential for New York’s libraries to fill a critical gap in our civic infrastructure, as well as the challenges and difficult choices the library systems face. It is supported by the Charles H. Revson Foundation. Read the rest of the series here.