Photo by: Texas governor’s office

Gov. Rick Perry in May 2013 signed the Michael Morton Act, which made Texas an “open file” discovery state. New York legislators are wrestling with several versions of discovery reform.

Alberto Ramos was a 21-year-old college student and part-time substitute teacher’s aide, aspiring to be a teacher, when he was accused and then convicted in 1985 of raping a five-year-old in the Bronx day-care center where he worked.

In a case based largely on the child’s sworn testimony, Ramos was accused of taking a girl into the Concourse Day Care bathroom during nap time. She was found to have vaginal bruising and her grandmother testified that when she picked her up from school, the child was crying. Amid media-fueled hysteria over a wave of child sex abuse in day-care centers, Ramos was found guilty.

Joel Rudin, who laid out Ramos’ case in The Fordham Law Review in 2011, writes that when Ramos was convicted of two counts of rape in the first degree “He screamed in agony, ‘Kill me.’”

In 1992, the conviction was overturned after the alleged victim’s mother filed a civil suit against both the New York City-funded day-care center and Ramos. The city’s insurance settled, but a civil defense attorney—who was able to obtain evidence that Ramos did not have access to for his criminal case—believed Ramos was innocent. The lawyer got permission to share the information with Ramos, who had been suffering severe abuse in prison for seven years on an 8-and-1/3 to 25-year sentence as a child rapist.

Among the omissions that could have aided in Ramos’ defense was a log showing that the grandmother who testified against him had not, in fact, picked the girl up from day-care that day in 1984. There was evidence showing other reasons for the child’s vaginal irritation and an interview in which the girl had initially denied Ramos raped her.

None of it had been turned over.

In 1963, the Supreme Court decided in Brady v. Maryland that, in criminal cases, prosecutors must disclose all evidence that could be “material” to the defense.

Yet when a criminal case is brought in New York State, evidence is not shared automatically with the defense. Instead, defense attorneys must file motions for evidence, and prosecutors are left to decide what constitutes “Brady material” that they must show the other side. Some argue that judges have discretion to force prosecutors to turn over more, but most don’t interpret the statute that way, according to Susannah Karlsson, a special litigation attorney for Brooklyn Defender Services.

Defense attorneys have long pointed to the role of New York’s restrictive discovery statute, Article 240 of the Criminal Procedure Law, in laying the groundwork for wrongful convictions by providing cover for prosecutors to withhold Brady material and allowing them to railroad defendants before trial.

But as DNA evidence has led to a mass of exonerations in recent years and stories like Ramos’ have surfaced, the movement to replace Article 240 has been taken up by a growing coalition of stakeholders lobbying lawmakers and rallying grassroots support. The calls to fix New York’s discovery statute include law enforcement and corrections officers, as well as lawyers, judges and the wrongfully accused—all echoing what Judge John P. Collins said in his opinion overturning the Ramos conviction, that an “unjust” conviction “reflects unfavorably on all participants in the criminal justice system.”

They’re pushing to replace or amend the state’s discovery statute by the end of this legislative session and they are cautiously optimistic that they’re gaining ground.

A history of concern

It is no wonder that Ramos’ innocence only emerged through an action in civil court, where a policy of showing the defense the entire prosecutor’s file prevails.

New York’s discovery law is considered one of the most restrictive in the country.

Justine Olderman, managing attorney of the criminal defense practice at the Bronx Defenders, which represents indigent clients facing charges, explained that most district attorneys interpret Article 240 to mean that the only evidence they must make available early on are statements made by the defendant and scientific texts or reports.

“Otherwise, that’s it,” she said, adding, “Most evidence is witnesses, most evidence is witness statements, most evidence is witness testimony.” Most evidence, that is, is the kind that defendants “don’t get access to until trial.”

The concerns date back decades. James Yates, now counsel to Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, as a judge in 1979 helped amend the discovery provision in New York, which he calls “the worst in the country.” The reforms required that certain basic pieces of evidence be shared, including police reports, which had previously been barred from discovery.

The reform passed, but the problem remained. What was laid out in 1979 “was supposed to be a floor, ” Yates says. But “most judges read it as a ceiling. That’s been the big problem in the law.”

He recounts the fictional courtroom comedy My Cousin Vinny, in which justice is served when the title character, an amateur lawyer played by Joe Pesci, saves two young men locked up in an Alabama jail for a murder they didn’t commit. Vinny uncovers evidence showing that the only witness to the crime had trees blocking her view and was looking through a dirty window. He gets police records revealing that people matching the description of the perpetrators had been arrested in the neighboring country.

Out-reformed by the Lone Star State

Had the trial taken place in Albany rather than Alabama, Yates says, Pesci’s character wouldn’t have had access to the information about other arrests, the witness’s name or statements, and maybe not even the name of the accuser. They were lucky to have been arrested in Alabama. “The kids in My Cousin Vinny would still be in jail in New York,” he says.

If they had to be arrested in New York City, they might be wise to choose getting nabbed in Brooklyn. Former Brooklyn District Attorney Charles Hynes voluntarily introduced a discovery-by-stipulation policy that eliminates some of the process and wait time for defendants to receive Brady material. There’s nothing in current New York law that says prosecutors can’t turn over their files early in the process—just that they’re not required to do so without the defendants motioning the court.

Still, Brooklyn is no panacea. Prosecutors are only required to turn over “Brady” material as it’s read under the current law—meaning they may still omit interviews with witnesses whom they will not call to testify, so long as prosecutors believe the information is not exculpatory, meaning that could lead to the exoneration of the defendant.

Both Rudin and Karlsson say the Brooklyn DA (the office, now led by Kenneth Thompson, did not return a call for comment) still whites out names of witnesses. And Rudin says there is a policy of instructing prosecutors not to take notes, “so if witnesses make contradictory statements they’re not written anywhere so there’s nothing to turn over.”

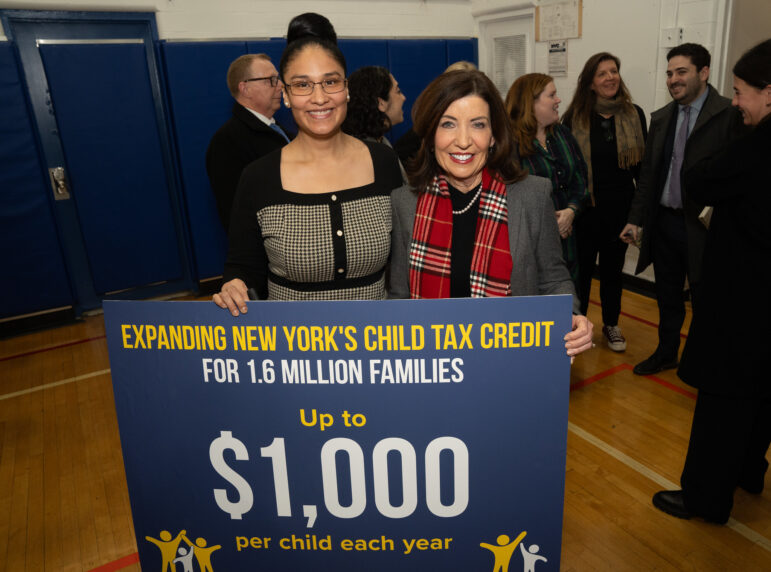

But compare New York to Texas, where last May, Gov. Rick Perry signed the Michael Morton Act, which expanded the state’s discovery law to an “open file” policy, following a prosecutorial misconduct case in which a Texas DA was sent to prison. The bill was named after a man the DA had wrongfully convicted of beating his wife to death in 1987 and who was released in 2011, after being exonerated by DNA evidence.

“Texas is a law-and-order state, and with that tradition comes a responsibility to make our judicial process as transparent and open as possible,” Perry said in a statement released upon signage, writing that it “helps serve that cause, making our system fairer and helping prevent wrongful convictions and penalties harsher than what is warranted by the facts.”

Claims of misconduct

Whatever rules a state imposes on sharing evidence, the system depends to some degree on prosecutors following them, and that doesn’t always happen. More than a third of the known DNA exonerations nationwide involved multiple claims of prosecutorial misconduct, according to the Innocence Project. A New York State Bar Association Task Force on Wrongful Convictions established in 2008 put out a report that looked at 53 wrongful conviction cases in the state; government practices involving evidentiary material accounted for 31 of the cases.

And according to Rudin, who has sued local officials over alleged prosecutorial misconduct, New York’s DA offices are doing little to stop prosecutors from breaking the rules.

“What my lawsuits have shown that there is a history of all the DA’s office in New York City doing nothing to prosecutors found guilty of Brady violations,” he says, and if there is no serious discipline meted out for such offenses, it sends the message “that we don’t really care about it all that much and that encourages more violations.”

In the Ramos case, Rudin sued the city and obtained discovery material showing “the Bronx prosecutor’s office, employing nearly 400 prosecutors and hundreds of support staff, has no published code or rules of behavior for prosecutors, no potential sanctions for misbehavior, no formal procedure for investigating or disciplining prosecutors, and no record-keeping of prosecutors with a history of improper behavior,” according to the Law Review article.

“Officials could identify just one prosecutor since 1975 who, according to the Office’s records, has been disciplined in any respect for misbehavior while prosecuting a criminal case. Officials claim that several prosecutors have been verbally chastised, or temporarily denied raises in compensation, but there is no apparent record of it,” Rudin wrote.

Ramos won a $5 million civil rights settlement in 2003, the largest wrongful conviction settlement at the time in New York State, according to Rudin. The Bronx DA would not comment on the Ramos case, but Robert Dreher, Bronx executive assistant district attorney says, “We have an extensive comprehensive training and ethical education of our attorneys.” He would not say how many people times prosecutors had been disciplined or how.

The problem, say critics, is the vast leeway prosecutors in New York are given in determining which evidence is relevant to a defendant’s case. In the case of Bill Bastuk, a former legislator and former Irondequoit councilman who was falsely accused in 2008 of raping a girl who took junior sailing lessons with his son, prosecutors tried to withhold the diaries of his young accuser.

Though the case was built on the father’s discovery of a diary entry accusing Bastuk of raping his daughter at the Rochester Yacht Club, Bastuk and his lawyer were only given a copy of that single entry at arraignment. The trial was delayed four times over the course of a year while they made motions to see more, he said. Finally, Bastuk’s lawyer got the diaries. One page, dated a month before the alleged incident, predicted that Bastuk would rape the girl, including the exact date and time of her attack. Another entry that said “I wish I could make this all go away, but my parents won’t let me,” Bastuk recalls.

The judge reviewed the diaries to determine whether they were discoverable and found an entry accusing another man of climbing through the girl’s window and raping her on a separate occasion. By the time trial began, the defense also had medical records showing she was in treatment for self-mutilation.

The jury met for only two hours, he said. Not guilty.

“These diary entries totally destroyed her credibility,” Bastuk says, adding “this was really a classic case of how discovery can impact a process.”

But Bastuk had a private lawyer—and stature. He did not await the trial from jail, as defendants who are deemed a severe flight risk or can’t afford bail must do. If his lawyer had not requested the material and a judge had not agreed to review the diaries and override the prosecution, he wouldn’t have had any right to them.

“This was really a classic case of how discovery can impact a process,” Bastuk says. “Without automatic discovery at arraignment, a defense attorney really can’t make the best decision on how to defend a client.”

Timing is everything

Indeed, the problem is often not just what information is available, but when.

In crowded jurisdictions like New York City, there aren’t enough resources to bring most cases to trial. Ninety-seven percent of federal and 94 percent of state cases pleaded out before trial, according to The New York Times. While pleas often render justice, innocent defendants can end up pleading guilty for fear of a longer sentence if they lose at trial, and guilty defendants may cop to more severe crimes than ones they committed—in part because defendants are often asked to take a plea often before any Brady information is made available to them.

In February, at a $50-per-plate Discovery for Justice fundraiser at Joe’s Place on Westchester Avenue in the Bronx, actors sought to put a face on the kind of pre-trial injustice rarely depicted on prosecutor-friendly television dramas.

A teenager, who claims to have fallen asleep watching a basketball game when the crime he’s been accused of occurred, is offered a plea in court. He has to decide whether to take it and avoid the possibility of jail time, or choose to go to trial without seeing any of the evidence against him. He screams at his helpless lawyer: “I want to prove my innocence but I don’t want to risk going to jail for — you’re saying five to 25 years — for something I didn’t do!”

Scene two takes place around the kitchen table, where his family agonizes over what they will tell the judge in the morning. And then it ends with a question: “How would you respond if that were your son?” Asking is Judge Fernando Tapia, who has worked in both Bronx civil and criminal courts and is a sitting judge, who has seen the statute in action.

“That’s no way to deal justice when you say: ‘You want to role the dice?’” he told the audience.

Witnesses in danger?

District attorneys in New York take advantage of the narrow discovery statute by holding on to information related to testifying witnesses until right before they take the stand—arguing that the current New York law protects witnesses from retaliation.

In a statement, the New York District Attorney’s Association says it is “committed to justice and fairness,” and is participating in the Justice Task Force convened by the state’s top judge, Jonathan Lippman, which is looking at the discovery issue. The DA’s Association does, however, point to the need for a “delicate balancing of a defendant’s right to informed representation and a fair trial with critical public safety and witness protection considerations.”

A spokesman for the DA’s Association pointed to Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance’s June 2012 Op-Ed in the New York Law Journal, in which he writes that “for every witness that comes forward, many would not think of giving information to authorities because they know that their identities and the substance of their testimony will be disclosed during the process of criminal discovery.” He points to the case of Daniel Everret, who while awaiting trail in jail for the 2008 murder of 13 year-old Scotty Scott in Harlem, was recorded on the phone instructing fellow gang members how to intimidate a witness.

However, the idea that more open discovery would put witnesses at risk was addressed in the Legal Aid Society’s most recent proposal to replace Article 240, which notes that similar reforms have worked in states with big cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, Miami, San Diego and Newark, where studies have shown defense lawyers and prosecutors approve of the discovery practices and find them efficient and fair.

“The streets are not bathed in blood,” Karlsson says.

Yates points out that alarmist scenarios like the one laid out in Vance’s Op-Ed would only apply to a very small number of serious crimes like rape and murder. In those cases, prosecutors can move for a protective order to shield some material from discovery—they’d just have to justify each concealment.

As it stands, not only are witnesses’ names concealed until right before they testify, prosecutors are not obligated to provide information obtained from witnesses whom they will not call. If witness A fingers the accused and witness B casts doubt on A’s story, he says, prosecutors don’t have to turn over B’s statement unless they plan to discuss it in court, which is highly unlikely. A legislative fix could eliminate the specification that only what will be introduced at trial must be turned over. “But the DAs oppose that because they don’t want the world to know about witness B,” Yates says.

Several reform proposals

Momentum has been slowly building for legislative change to the discovery law.

Two 2012 U.S. Supreme Court decisions established defendants’ rights to effective counsel during pre-trial plea bargaining. Interpretation of the rulings differ, but the dual decisions have given extra weight to the argument that pre-trial evidence is part of the right to a pre-trial defense.

Judges have increasingly spoken out about injustices they have helplessly witnessed — such as defendants forced to accept or reject a plea without knowledge of the evidence against them. And advocates have argued that New York’s discovery law strains already overburdened courts and jails by forcing defense lawyers to file motions for evidence they should be entitled to as a matter of course. As their lawyers fight for material that other states would require prosecutors to turn over automatically, defendants often sit behind bars, with taxpayers footing the bill. The longer they wait, data has shown, the more likely they are to plead guilty.

People who have seen first-hand some of the problems with the justice system are among those on the front lines pushing for change.

Jeffrey Deskovic, who served 16 years in prison for murder and rape until DNA evidence exonerated him, is using his multi-million-dollar settlement against Westchester Country to start the Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation for Justice, which is speaking out on the issue.

Meanwhile, Bastuk and his wife lead a grassroots coalition to prevent wrongful indictments and convictions called It Could Happen to You, which has been working with New York State Chaplain’s Association chapters around the state to push for legislation that would require what Bastuk calls the Triple A: “All the evidence, automatically, at arraignment.”

Discovery for Justice was founded by retired NYPD Detective Carlton Berkley, who is leading the push to rally support in the criminal justice community to replace Article 240, with unofficial but unmistakable support from Tapia. The flaws in the system might be obvious to lawyers, but it’s news to many cops, Berkley notes. “A lot of police officers don’t know that,” he says. “We always thought that the system was fair.”

Activists are not unified around a bill, but are making frequent trips to Albany. They have begun leaning heavily on their state senators, lobbying in particular state Sen. Jeff Klein, whose district covers parts of the Bronx and Westchester and leads small but powerful Independent Democratic Conference that shares power with senate Republicans.

Apart from the “triple A bill,” there’s one drafted by Legal Aid, which has been introduced before and would replace Article 240 with an open file policy. Another, more recent, Legal Aid bill, taken up by State Sen. Diane Savino, an IDC member, calls for evidence to be turned over in phases.

John Schoeffel, an attorney with Legal Aid’s special litigation unit, says the Savino bill takes into account concerns of the District Attorneys Association by giving more time for certain disclosures, and is aimed at avoiding the fate of earlier bids to fix Article 240, which wilted under prosecutors’ opposition.

There are two other bills that don’t replace article 240, but mend it— one that would give judges discretion over what to turn over and another “Brady fix” that would force prosecutors to turn over everything favorable to the defense.

Neither Klein nor the IDC responded to repeated requests for comment. But an advocacy day on Feb. 11 brought grassroots lobbyists to his office, and a group of community leaders including Tapia plan to meet with Klein on April 3.

At the same time, the New York State Justice Task Force has also been focusing on discovery reform and has come to a point of action. According to the 2014 State of the Judiciary delivered by Lippman, the task force is “recommending that the prosecution disclose — well in advance of the scheduled trial date — the identity and any prior statements of all witnesses who have relevant information, whether the prosecution intends to call those witnesses at trial or not.” Also, before trial, the task force recommends that both sides exchange written reports or summaries of their anticipated testimony by expert witnesses.

“We will shortly be submitting legislation proposing these and other significant changes,” Lippman said in the speech.

Nancy Ludmerer, counsel and a member of the task force, says members are in the process of voting on their specific recommendations and that the results will be released within the next several weeks. Then Lippman will decide how to effect those reforms.

Rudin, for his part, said “open file discovery is only the beginning,” and that the law must also cover unrecorded interviews, and create consequences for prosecutors who conceal evidence.

Stakeholders disagree about the best remedy. But there seems to be consensus that a long-awaited tipping point is within reach for changing New York’s antiquated discovery law.

“There is no truth-seeking justification to hide this material,” Karlsson says.

One thought on “Will New York Follow Texas In Criminal Justice Reform?”

Pingback: Repeal the Blindfold Law - Roosevelt Institute