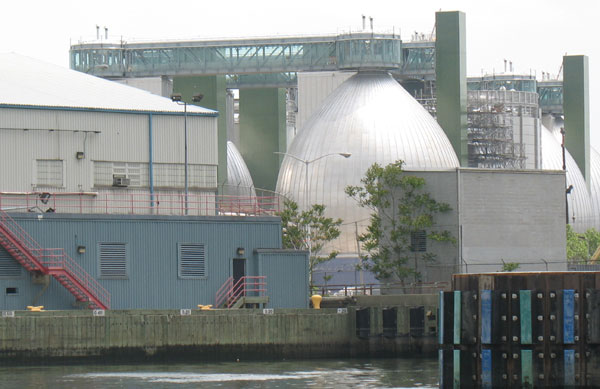

Photo by: Jarrett Murphy

The Newtown Creek Water Pollution Control Plant. The 1989 charter revision created a mechanism for communities to resist being the site of disproportionate numbers of sewage plants, waste stations and other problematic facilities. But a loophole has allowed that process to be bypassed. Community advocates want the charter revised to fix the flaw.

In his first three years as mayor, Michael Bloomberg appointed three commissions to change the city charter. Talk of a fourth such panel began with the mayor’s 2008 state of the city address, when he said, “Today, I am pleased to announce that we will appoint a new Charter Revision Commission that will conduct a Ron Lauder that a commission would be appointed after the 2009 elections to revisit term limits. But a commission wasn’t actually empanelled until March 3 of this year.

From the mayor’s first talk of the commission two years ago, its potential workload has been compared to the 1989 charter revision commission that totally revamped city government.

And the 2010 commission adopted that sweeping ambition, scheduling hearings that considered term limits, a menu of ways to increase voter participation, a potential re-balancing of the powers of municipal officials, comprehensive changes to the city’s mechanism for monitoring government ethics and a rethinking of how the city makes decisions about land use.

But the 1989 commission had a whole year to consider the proposals it put to the voters, and its work built on that of an earlier panel that existed from 1986 to 1988.

This year’s commission chose a far smaller window. At its public hearings, many speakers implored the commission to take its time and put off any proposals until the 2011 or 2012 elections, rather than racing to finish before the 2010 vote. But the commission has been aiming to get a ballot proposal done for this year.

And when the current charter revision commission’s staff published its preliminary recommendations earlier this month, it suggested a stripped-down list of ideas, arguing that those were the ones that the commission “has the time and resources to prepare for the ballot in November.”

Monday night was the first chance for the public to weigh in on those recommendations, which commission chairman Matthew Goldstein has referred to as a “living document,” subject to change. The theme of the testimony at Brooklyn College was that the staff’s list of topics–term limits, instant runoff voting, easier ballot access and a smattering of administrative reorganizations–was far too narrow.

“While we support the idea of putting certain items on the ballot this year and naming other issues to be considered in 2012 by reconvening this commission or forming another, Citizens Union feels the current staff report is weighted too heavily toward deferral and too lightly on action,” said Citizens Union executive director Dick Dadey. “Quite simply, we urge you to reach further and aim higher.”

Citizens Union (CU) –given extraordinary access to the commission that included piping in a CU staffer’s testimony via telephone–pressed for the commission to consider a system of voting that would eliminate party primaries. The union also wanted the commission to take up independent budgeting for the public advocate and borough president and changes to City Council discretionary funding and the practice of extra stipends (or “lulus”) for favored members. While admitting that some land use topics are complex, CU thought some were no-brainers, like fixing loopholes in the 1989 “fair share” provision that allowed the city to circumvent mechanisms intended to spare certain neighborhoods from having to absorb a disproportionate number of waste stations, sewage plants and similar facilities.

Other witnesses echoed those points. Charter Revision Commissioner Hope Cohen resisted the push to expand the commission’s agenda, noting that the commissioners have to select issues on which there is enough evidence to act. “It’s also right for us to say ‘No, it’s not time,'” she said.

But Goldstein promised to meet with Eddie Bautista, executive director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, after Bautista–who has pressed for attention to the flaws in fair share–testified, “My question for you guys is, how long do we have to wait?”

The worry among advocates on fair share and other issues is that after this commission lapses–which it will as soon as it places questions on a ballot–there is no guarantee that the mayor will appoint another one. The problems with fair share have existed for 21 years.

The issue of nonpartisan elections, on the other hand, was raised by a 2003 charter commission and defeated by voters. Citizen Union wants it to live again, albeit in a slightly different form: “Top two” elections are not strictly nonpartisan, because candidates can list their party affiliations. But instead of separate primaries open only to registered party members, “top two” would feature a single primary, with the top two vote getters–they could both be Democrats–moving on to the general election.

Arguing for a shift to “top two,” Citizens Union’s John Avalon testified that “We are in danger of having closed partisan primaries replace general elections where all New Yorkers have a voice and a vote,” a reference to the dominance of Democratic party candidates in the city in most general election races.

But CUNY professor John Mollenkopf disputed the idea that “top two” will increase voter turnout. That idea, he says, “is not supported by fact or logic,” adding: “Party affiliation is associated with higher turnout and parties are good at mobilization.”

The commission will on Wednesday continue its final round of public hearings:

Wednesday, July 21, 6 p.m., Bronx Community College, Nichols Hall, Room 104

2155 University Ave., Bronx

Monday, July 26, 6 p.m., Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building, 163 West 125th Street, 8th Floor, Manhattan

Wednesday, July 28, 6 p.m., Queen Borough Hall, 120-55 Queens Blvd.. Kew Gardens, Queens

Monday, August 2, 6 p.m. PS 58 – Space Shuttle Columbia School, 77 Marsh Ave., Staten Island