Van Alen Institute

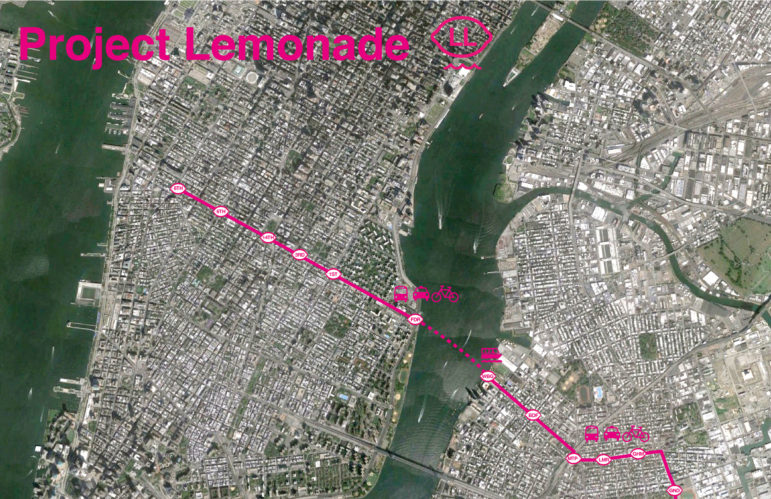

The winning concept at a recent Van Alen Institute charrette imagined moving commuters across underutilized infrastructure, combining ferry use across Newtown Creek with routing trains over an unused freight line.

The impending shutdown of the L-train slated to begin in 2019 could have a significant economic impact on local businesses, which depend heavily on foot-traffic. But community members, who had a rough start communicating with the MTA about the shutdown, have become more welcoming to the gamut of ideas that city and outside planners have created to ease the transition.

The L train carries 225,000 people daily, according to the MTA. But the train-line, which is 92 years old, has been tested by a large increase in ridership in recent years. When the MTA announced earlier this year that they would need to shut the line down to repair Hurricane Sandy-related damage to the Canarsie Tunnel, local business owners grew concerned.

“What’s really going to screw us up is that people aren’t going to come from the train station,” says Stewart Borowsky, 48, owner of Union Square Grassman, a business that has been at the Union Square Greenmarket for 22 years. Borowsky says the shutdown plans point to a larger problem the city has had keeping its transit infrastructure up to pace with development.

“It’s amazing that we’re bringing more people into the city, we’re doing a great job,” Borowsky added, “but the bottom line is infrastructure needs to be expanded at the same pace.”

Many business-owners are beginning to look at the L Train shutdown as a way to finally get those solutions, and some are starting to look at the shutdown as both an economic hardship and as an opportunity for long-time residents to get better transit infrastructure.

“I was one of the loudest voices for no shutdown, no way,” says Felice Kirby, founder of the L Train Coalition, a community group formed to help locals communicate with the city about the shutdown. Kirby is a long-time business owner who ran the bar Teddy’s in Williamsburg, which she purchased from its previous owners in 1987.

After some initial tension with the MTA, Kirby says she is enthusiastic about the way the community has come together to communicate with the MTA about alternate transit options.

“We talk to each other and meet regularly, I’ve never seen anything like it,” Kirby says.

Kirby is proud to point out that everything the coalition does is on a volunteer-basis. She says the group has reached out to every elected official and community board along the L line in an attempt to show the human cost to an L train shutdown and its impact on local businesses.

Kirby sees a variety of solutions as potentially helpful, including more bus rapid transit and express bus service. She’s particularly interested in ferry service, which she says could alleviate the most hardship. While other transit solutions would just move the burden to another part of an already overtaxed mass transit network, the ferry solution would utilize waterways that most New Yorkers don’t regularly use. And, she adds, “a ferry is fun,” something that would benefit business-owners in the food and drink industries.

Kirby says that the attention surrounding the L could lead to bold transportation solutions that will benefit the community.

“Maybe we’ll try something we’ve never had the political will to try,” Kirby says.

She has a wish-list of ideas that could help neighborhood businesses, including emergency, temporary commercial rent relief. She believes this is unlikely but wants to take advantage of the moment.

The coalition also welcomes ideas from outside planners and researchers about how to mitigate the economic impact of a shutdown.

“We would like to know what Columbia, Pratt, NYU thinks,” Kirby says.

Other organizations have been pro-active about collecting proposals to move commuters and mitigate the shutdown’s economic impact.

On June 12 The Van Alen Institute hosted an “L Train Shutdown Charrette”, a competition between teams of designers, engineers and urban planners to create solutions to the L-Train shutdown. Judges included a project manager from the Department of Transportation and an editor from New York Magazine. The winning team was awarded $1000.

Basing a competition around a train shutdown may seem unusual, and it did invite some whimsical proposals, like an inflatable floating tunnel idea described as “wild,” by David Van Der Leer, director of the Van Alen Institute. But Van Der Leer says the intent of the charrette was to find practical solutions that would lessen the economic impact of the shutdown. “It’s not about making cool designs, it’s important you’re trying to alleviate a stressful situation and visualize the opportunities for improvement,” Van Der Leer says.

The winning project imagined moving commuters across underutilized infrastructure, combining ferry use across Newtown Creek with routing trains over an unused freight line. Dillon Pranger, an architectural designer who was on the winning team, says that they thought of using Newtown Creek because the area is an EPA superfund, potentially eligible for federal brownfield grants to fund the project.

The Regional Plan Association, an urban policy think-tank, presented its own set of proposals to the MTA in March. Among their recommendations was closing 14th Street to car traffic and using the lanes for select bus service. The plan would allow loading and unloading from commercial vehicles during specified times.

Kirby says she’s still communicating with the city about the shutdown, and says she now has a clearer picture of how complex the problem is.

“It went from very dire, to wow, this is a very big problem that needs a whole giant array of actors to solve it,” Kirby says.

More photos from the Van Alen Institute Charrette:

Van Alen Institute

Some concepts for navigating the shutdown involve making the 14th Street corridor carry more (and maybe exclusively) mass transit.

Van Alen Institute

The inflatable floating tunnel approach.

Van Alen Institute

One thought on “Ideas for Handling L-Train Shutdown Range from Fun to Far-Out”

No real good alternatives to the ‘L’ train. You all better hope the MTA completes the job on time.