Adi Talwar

One of the site adjacent to the rezoning area that is controlled by the EDC.

When the city initiates a neighborhood rezoning, city-owned land is often a vital tool to build housing with deep levels of affordability or to create other needed community facilities. In East New York, for instance, heeding community members’ demands for more guaranteed affordable housing, the city agreed to prioritize the development of a nearby public property outside of the rezoning area.

The city’s current plan for Staten Island’s Bay Street corridor, one of the seven neighborhoods targeted for a rezoning under the mayor’s plan to build or preserve 200,000 units of affordable housing, includes development proposals for multiple public parcels outside of the rezoning area. Yet those proposals have created concerns among some community members who say they will generate insufficient affordable housing and open space.

The proposals are embedded within the city’s draft scope of work released by the Department of City Planning (DCP) on May 13, which offers the most detailed rendering of the Staten Island zoning plan up to date. The plan involves transforming Bay Street, currently zoned for manufacturing, and Canal Street, now zoned for low-density apartments, into thriving mid-rise residential and commercial corridors. It also details proposals for five public sites within the vicinity of Bay Street.

An empty building at 55 Stuyvesant Place owned by the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene would be transferred to a private landlord for the development of a business incubator. A sanitation garage at 539 Jersey Street would be relocated and the site developed into housing, potentially with 30 percent of units at below-market rates. And a parking lot at 54 Central Avenue would be sold to a private owner for the creation of more office space.

“Office use at this site would provide job opportunities to the growing population of St. George and nearby Stapleton. A commercial office space would be consistent with the context of St. George as a downtown commercial and civic core of northern Staten Island,” the scope reads.

Nick Petri, an organizer at Make the Road and a representative of the Staten Island Housing Dignity Coalition, says the three sites are surrounded by residencies and should be used to address the neighborhood’s rising rent burden.

“The tenants are saying, ‘I’m terrified of being pushed out,'” says Petri. “Is market-rate office space, owned by a private developer for private gain, the best use of our public resources? And I think on the Jersey Street site I would also ask the question…Why only 30 percent affordable?”

Councilwoman Debi Rose, however, expressed excitement for the transformation of the three public sites.

“The redevelopment of 539 Jersey Street has been a priority of mine since I took office,” she said in an e-mail to City Limits, adding that she had secured funding in last year’s budget for the relocation of the sanitation garage. “I look forward to seeing it replaced by a commercial and residential complex that will offer neighborhood amenities such as affordable and market-rate housing, a grocery store, a bank and more. I also look forward to the commercial possibilities that the redevelopment of 55 Stuyvesant Place and 54 Central Ave can bring to the St. George neighborhood.”

Others are more concerned with the development of two city-owned sites to the east of the rezoning area—and in contrast to the other advocates, they’re making calls for less residential density that the city’s current plan. The properties lie within the boundaries of the Special Stapleton Waterfront District, where the Economic Development Corporation is leading an effort to revitalize the waterfront.

A community task force in 2006 originally proposed the development of 350 units of housing, along with two public plazas, a sports complex and commercial spaces. The city’s current plan varies significantly from this vision. Nine hundred residential units are already underway, according to the developer’s website, along with retail, parkland, a volleyball court and dog run. EDC has preliminary plans to develop roughly 600 more units to the south and 600 on the two parcels adjacent to the rezoning, of which 50 percent would be affordable.

DCP’s draft scope for the Bay Street rezoning includes a text amendment that would increase the allowable buildings heights on these two parcels from 55 feet to 125 feet.

Mike Penrose, president of the Ward Nixon Association and a member of the Staten Island Citizens Planning Committee (SICPC), says SICPC is concerned with the influx of residential development and wants EDC to reserve the remaining parcels for public recreation.

“We want a Brooklyn Heights-type waterfront,” he says. “Without it, we see it as a massive amount of building with limited open space for recreational use.”

He adds that the Let’s Rebuild Cromwell Coalition, which formed after the collapse of Tompkinsville’s neighborhood recreational facility, are concerned about the lack of recreational facilities and fields for the neighborhood’s youth. The Coalition is also pushing the city to expand the nearby Lyons Pool into a full recreation center.

Leonard Garcia-Duran, director of the DCP Staten Island office, said the proposals for the five sites are still preliminary and have been sketched out so the city can study how development would impact the area.

“There’s a lot of planning that has to occur with the public and with EDC,” he told City Limits, adding that at the two waterfront sites “there’s a balance that needs to occur between whether or not we can get more affordable housing and … how do we get waterfront connections for the neighborhood.” In addition, a city presentation from the parks department says that expanding Lyons Pool or developing a new recreation center is one of the city’s top priorities for the corridor.

Asked why the city was not pushing for 100 percent affordability on any of the public sites, Garcia-Duran said, “100 percent affordable makes it much more of a challenge to get to lower income levels, so there’s got to be a balance. … It’s going to require additional subsidies, and the question is how much subsidies does the city have to offer to make them affordable?” City housing officials believe mixed-income housing allows developers to serve households with very low incomes because the market-rate rents offset the costs of providing housing at low rents.

Overall, the city’s draft scope estimates that about 40 percent of projected units (1,039 of 2,569) will be rented at below-market rates. This estimate is based on the assumption that the city will apply the mandatory inclusionary housing option in the rezoning areas, requiring that 30 percent of the units are affordable to families making 80 percent AMI (in addition to requiring 50 percent affordable housing at the Stapleton waterfront sites).

But that assumption comes at a very preliminary stage. The total number of affordable units could be less if DCP recommends—and City Council approves—another MIH option with deeper affordability levels. Indeed, a spokesperson for Councilmember Rose said she “will be seeking the deeper affordability options, with details to be worked out in the negotiating process.”

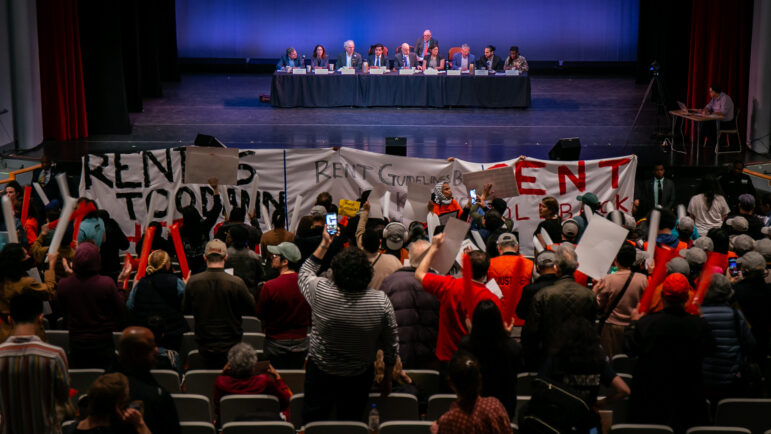

The city says it has not yet evaluated which mandatory inclusionary housing option would be most appropriate for the Bay Street Corridor. It is clear, however, that officials don’t view Bay Street as another East New York, where 35 percent of the population made below 30 percent AMI and community members called nearly unanimously for deep affordability. At a panel discussion last Wednesday, director of the Department of City Planning Purnima Kapur cited Bay Street as a rezoning area that is not low-income—and it’s at least true that the Bay Street area is income diverse, with 23 percent of residents earning below 30 percent AMI and 48 percent earning above 80 percent AMI.

Petri, however, notes that the city’s definition of the Bay Street context area, which is based on census tract boundaries, excludes several low-income housing complexes slightly south of the parameters, and fears the city will overestimate the income levels of tenants who could be affected by the zoning and the potential for displacement.

After DCP presented their latest updates at community meetings on Thursday and Saturday, community members had a range of reactions. Alicia Averett, a Bay Street resident, said she was fearful she would be displaced by rising rents and that the plan should include “more affordable housing, especially for seniors,” while local business worker Nadette Staša said she was thrilled by the prospect of increased support for small businesses and new cycling and pedestrian paths.

“Yay city of New York and de Blasio!” she said.

City Limits’ coverage of housing and development is supported by the Charles H. Revson Foundation.

6 thoughts on “Staten Island Rezoning: Should Public Sites be Used for Housing, Open Space?”

Still a somewhat dangerous area, the new developments will help. But I’m afraid the ‘affordable’ housing will end up as low-income housing which will hurt the area further. Conditions vary block by block. People are buying and renovating old homes in the area, other blocks are a mess.

There is no way they are going to get 50% affordable units without major outside subsidized bond financing. The NYCHDC just does not have the capital for a project of this scale, combined with so many others. It would have to come from the HUD HFA, which as far as I know still only does 20% affordable projects. This is always a problem with the Department of City Planning. They have had grand hopes for Stapleton for 30 years – the co-ops and condos there now in converted warehouses were done in the mid 1980s. But economics eludes them, or at least they overestimate how much the city relies on trickle-down economics.

Still a well-written article though!

I live in a small house with a yard in Stapleton in the Bay Street Corridor area and worry about being displaced if my landlord decides to sell to a developer who will demolish my and neighbors’ buildings to build bigger apartment buildings. We won’t qualify for low-income housing or be able to afford expensive new ones, so where will people like us go? This is a settled residential neighborhood with many longtime homeowners and renters, primarily small one- or two-family homes (as well as some larger very lovely Victorian houses) along Van Duzer Street, a block from and parallel to Bay. Most of the denser housing would be on the water side of Bay, which is a flood zone and was badly affected by Hurricane Sandy.

Unfortunately that is what happens in many cases. But you have to find out what the proposed zoning will be for your current address. If it’s part of the proposed upzoning then your landlord may indeed sell.

NYC zoning districts:

http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/zoning/districts-tools/zoning_data_tables.pdf#page=1

Awesome post.

Slots does not offer “real money gambling”.