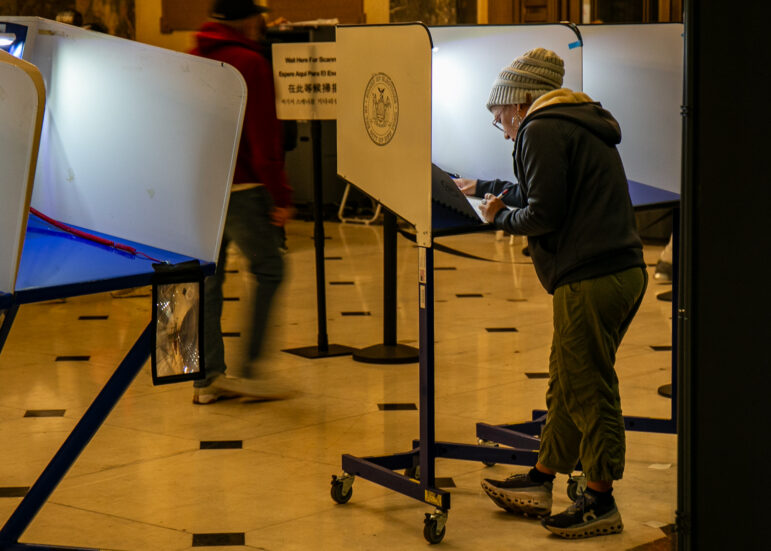

Photo by: Gerard Flynn

A final meal awaited rats in this bait station seen in early 2013 on Pacific Street not far from the Barclays Center.

Apparently, Mayor de Blasio is down with carriage horses and ferrets, but not so much with rattus norvegicus—a.k.a. the Norway Rat, those rodents who scurry along subway trackbeds and dart from bag to bag on garbage day.

The Daily News reports today that the administration is earmarking new funds for a team of inspectors to go after “rat reservoirs” in sewers and parks where large numbers of rats live and breed.

Despised as they are, rats deserve grudging admiration. It’s been written that they can survive a 50 foot fall and tread water for three days. They can chew through cinder-block and squeeze through openings no wider than a quarter. They are, in short, a formidable enemy.

Key background reading for the battle ahead can be found in Gerard Flynn’s story of last year on the question of whether gentrification and development and the impact of superstorm Sandy were somehow changing Brooklyn’s rat population—drawing it where it hadn’t been before, pushing it from where it had been.

While little hard data about population size existed (although the city’s Rat Information Portal did give us each a chance to see how our own neighborhood ranked in rat terms), Flynn did uncover important facts about how rats live:

Rats live in nested colonies many feet underground that are organized hierarchically. Colonies are dominated by the largest male, the notoriously promiscuous King Rat—usually the fattest one, who marks his territory by maiming others. A rat found with part of his tail bitten off is marked for lowly status. Once the colonies are disturbed, rats will exit through a “bolt hole” in the burrow system and seek shelter elsewhere.

Stories of gigantic rats are often discounted by experts as mere mythologizing. Although mature Norway Rats at two months old can span more than 18 inches, they rarely weigh more than a pound. The average weight in a city is closer to half that. The Norway Rat’s ability to raise its fur catlike when threatened usually explains the reports of enormous rodents.

But size isn’t everything: A female rat in the wild is mightily fecund. Under ideal conditions she may produce between 25 and 35 pups or more in a year, if she lives that long (most rats in the wild don’t make it past six months). Less than two days after her 22-day gestation period, she is ready to start the cycle again.

However, fertile as she is, she can’t breed if she can’t feed. And that’s the key to stopping rats.