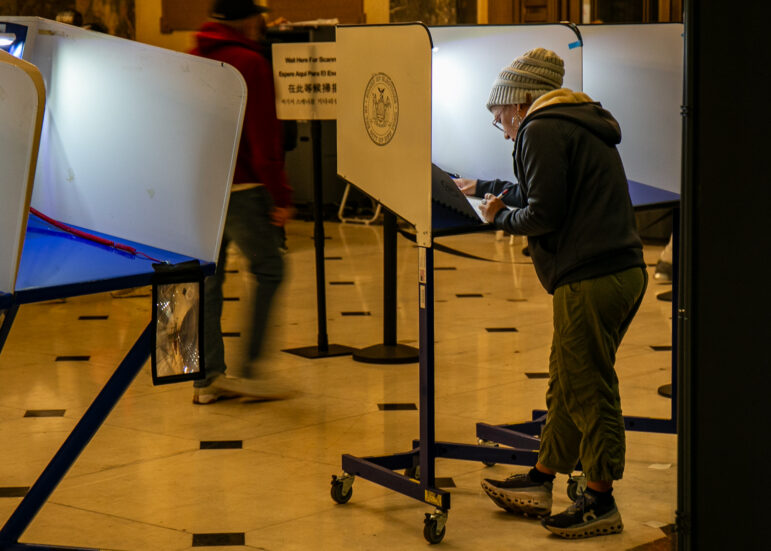

Photo by: Parker 2010/wellingtonsharpe.com

Sen. Kevin Parker faces trial on assault charges after his primary contest against perennial candidate Wellington Sharpe.

Like eight other sitting state senators in New York City, Brooklyn’s Kevin Parker has to win a primary on September 14 and, like all state officeholders in the city, a general election in November. But in between those contests the four-term incumbent faces a unique challenge: the next court date in his prosecution on charges of roughing up a photographer last year.

That’s one reason why the Daily News anchored its September 6th editorial with a denunciation of Parker’s bid for re-election in the 21st senatorial district, which encompasses parts of Boro Park, Kensington, Ditmas Park, Flatbush, Rugby, Remsen Village and Farragut in central Brooklyn.

“Brooklyn state Sen. Kevin Parker has proven himself unfit for office by using his mouth and fists,” the paper wrote, noting Parker’s 2005 arrest for a fight with a traffic agent and a later accusation by a staffer that Parker shoved her and broke her glasses. Then there was the alleged assault on the New York Post photographer last year, for which Parker is due in court October 16. So far in 2010, Parker has had a profanity-laced screaming match with Sen. Diane Savino at a Democratic caucus, erupted at a Republican senator during a committee hearing and labeled Albany Republicans “white supremacists.” The Daily News declared: “This hothead has to go.”

Nor is the News alone in wanting to retire Parker. Former Mayor Ed Koch’s NY Uprising dubs Parker an “enemy of reform.” Mayor Bloomberg implicitly declared himself through with Parker two years ago when he backed Parker’s primary challenger. Fellow Democrat Sen. Ruben Diaz, Sr., of the Bronx last week took Parker to task after the two men had a heated argument on the Senate floor.

But despite all the bad press, Parker is no pariah. Senators Liz Krueger and Tom Duane, progressive voices often identified with reform, have given him a combined $8,500 in campaign contributions. Unions have also provided substantial funding, led by 1199 SEIU, which donated $6,000. This week Parker won the endorsement of District Council 37, the city’s largest union. He already had the backing of the Working Families Party.

Both DC37 and WFP broke with some incumbents this year, but stayed with Parker. And both groups say it’s about more than the fact that Parker is likely to win. DC 37 Political Director Wanda Williams says that Parker “has been a longtime friend of this union and its members.” In a statement, she added: “Over the years, Sen. Parker has been a fierce advocate for this institution’s legislative and budgetary priorities. We believe he is an excellent legislator.”

Working Families Party spokesman Dan Levitan concurred: “He’s been a very reliable progressive vote in Albany. He’s been an outstanding ally on ensuring a fair budget, on tenants’ rights, on workers’ rights.”

Record vs. reputation

Parker, who worked as a political staffer before he joined the Senate, was first elected in 2002, winning a five-way primary that included Boro Park power Noach Dear. He won a primary rematch against Dear in 2004 and handily defeated Dear again in 2006. Two years ago, he cruised against Councilmen Simcha Felder of Boro Park (who had Bloomberg’s support) and Kendall Stewart of Flatbush.

In an interview with City Limits, Parker says his proudest accomplishment in the Senate was last year’s abortion Clinic Access Bill, which he called “the most protective clinic access bill in the entire country.” He added: “It significantly increased penalties for people who would attack those working at or coming to seek treatment at a clinic.”

Parker has introduced legislation to authorize utilities to pay up-front for energy-efficiency retrofits of homes and businesses, and then recoup the outlay by charging the customer over time—a method called “on-bill financing.” This approach, he says, would not only encourage energy savings but also spur green jobs creation. Other bills he has written would expand translation services in courts and hospitals, track intellectual property created by state employees and permit the Thruway Authority to award contracts worth less than $100,000 to minority and women-owned business without competitive bidding.

It was a discussion about minority and women owned businesses that triggered Parker’s outburst at a senate committee hearing earlier this year, when upstate Sen. John DeFrancisco took issue with a nominee for the state Power Authority who had written that without minority set-asides, white men would get all state contracting work. “Sometimes people have to lash out at everybody because they are at a point in their life where they haven’t quite made it yet and therefore everybody who has made it, there’s something wrong with them,” DeFrancisco said in the April incident. “You don’t have to be black in order to walk in someone’s shoes. … My father didn’t go to high school. He painted high schools, for crying out loud. I was the first one to go college.”

Parker interrupted, shouting that DeFrancisco was “out of order” and screaming, “You don’t understand that there is racism and there is discrimination occurring daily in this state and in this country … and that’s why they have policies to counteract that.” He later said that “white supremacy” was “what John DeFrancisco and a lot of the Republicans are.” He later apologized for his “zealous advocacy.”

Parker says the April outburst and the criminal allegations against him—he faces felony counts of assault and criminal mischief among other charges—do not come up in his district. What is on constituents’ minds, he says, is the lack of jobs. Parker says his office helps pair workers with potential employers. His top legislative priority is an “educational leave act” that would mandate that employers give workers up to 16 hours a year to spend at parent-teacher conferences, school concerts and other school events that occur during work hours.

He has also called for raising taxes on wealthy New Yorkers. Indeed, Parker insists that the Empire State can close the yawning budget gaps projected for future years without cutting state workers’ pay or retirement benefits. “We’re in the situation we’re now in not because we overspent. We have a problem because of the collapse on Wall Street and the job crisis. We just don’t have people paying taxes as they have in other years. We ought to be looking for opportunities to bring the revenue side of our ledger up to where we used to be.”

A frequent challenger

In rebuking Parker, the Daily News said voters “have a better alternative in challenger Wellington Sharpe. … An educator and businessman, Sharpe is calling for comprehensive reform of Albany, including transparency on personal finances for members of the Legislature.”

But a person with knowledge of the editorial board’s work tells City Limits that “any living homo sapien would have won support” against Parker.

Sharpe is a familiar name to voters in central Brooklyn. In 1999 he lost a school board race by eight votes. He tried but failed to get on the ballot for state senate in 2000. In 2001, he placed fifth in a City Council primary. The following year he ran in a different State Senate district (the 20th) and took 25 percent of the vote. He was the third-place finisher in the 2004 21st district State Senate primary, in which Parker beat Dear. In 2007, Sharpe lost in two special elections for a City Council seat. Last year, he threw his hat in the ring for a different Council slot but didn’t make the ballot.

Sharpe has raised $347,000 for his various candidacies, but more than $230,000 of that is from Sharpe or his company. Of the $143,000 he’s reported raising this year, only $1,075 came from people other than Wellington Sharpe.

After the first special election race in 2007, Sharpe was fined $9,000 by the city’s campaign finance board for taking an over-the-limit in-kind contribution and failing to provide documentation. His second campaign that year was fined $17,000 for failing to report who was behind third-party payments to his campaign workers and for “falsifying contribution information and claiming public matching funds on the basis of falsified contribution claims.”

Sharpe did not return a call seeking comment.

His website indicates that he emigrated to New York in 1974 from Jamaica, worked simultaneously as a cabbie and a bookkeeper, earned his GED in night school and went on to John Jay and Baruch colleges, eventually obtaining a master’s degree. In 1991, he founded Nelrak, a for-profit preschool and kindergarten in Bed-Stuy.

There is no mention of policy on Sharpe’s website beyond an undated entry on police brutality that reads: “Maybe it is time for an independent Federal monitor to intervene and help the NYPD to better police itself for the betterment of our community.” In the 2001 city Voters Guide, then-Council-candidate Sharpe vowed to “Work with special interest and business groups to bring computer technology to every child, convene public hearings on matters crucial to the quality of life of residents” and “Pay special attention to the quality of healthcare in the district,” among other promises.

On his website, Sharpe pays homage to the contributions of Caribbean-Americans—one of three key groups in the 21st district. African-Americans and Jewish communities in Boro Park are the others. Sharpe apparently hopes some combination of those forces will heed the message he’s been sending for more than a decade. “Now [Sharpe] is calling for a full reform of city government,” the site reads. “He is hoping that someone will listen now. “