February 1983

History is always a summary. It weaves together disparate threads of individual experiences, and some threads color the pattern more than others. The conventional narrative of New York City after the 1970s fiscal crisis emphasizes what mayors, police commissioners, developers and other powerful people did.

But that’s not the story. It’s just one.

Since its founding 40 years ago this month, City Limits has told a different tale—one that has sometimes complemented, and other times contradicted the official version. That’s because we talked about the New York seen by people like tenants, single mothers, strikers, prisoners, advocates, social workers, the homeless, the young and others who, when they strolled the traditional corridors of power, did so with a visitor’s pass.

As the excerpted stories below indicate, those New Yorkers had their own kind of power, and the city has been shaped by it. The stories are just snippets from our work over the past four decades. They reflect the history that City Limits saw and the New York it was founded to cover.

1976

A Message from the Editors

February

With this introductory issue of “City Limits,” the Association is responding to a need, expressed at our retreat last September, for more communication within and among people and organizations in the movement to save and improve housing for low- and moderate income residents of New York City. We hope that our members and affiliate groups as well as others concerned with our city’s housing problems will find this publication to be useful. To insure that it will serve the community housing movement and to make future issues better and more effective, we urge our readers to keep in touch with us. Please let us know what you think of this issue; how should it be improved; what do you want to see included in future issues; what should be left out?

1977

Organized Community Groups Help Win Rent Control Extension

May

In a surprise move, the Republican party members who control the New York State Senate announced on April 25th that they would introduce and vote for legislation extending, for four years, the present Emergency Tenant Protection Act .. What is significant about the Republicans’ action, in addition to assuring thousands of New York City rent-stabilized and upstate rent-controlled tenants of continued protection, is the manner by which it was brought about. … Without a well-planned, coordinated and executed action program by the organized tenant groups, the turn-about would not have happened

1978

Uphill Battle to Brake the Slide of 590 Parkside

By Bernard Cohen

June/July

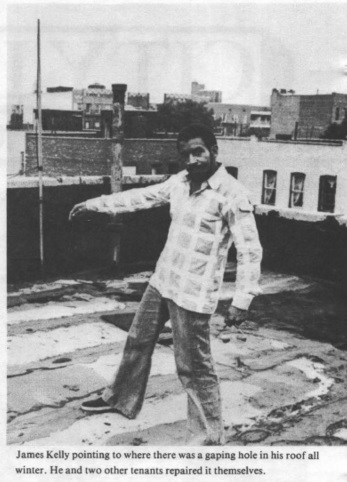

Mabel Kelly, 59, covers her white lamp shades with plastic to protect them from the soot that blows so thick into her apartment that she sometimes thinks her building is on fire. Downstairs, the mustard-colored wall of her son James’s kitchen looks two-toned from the neat line marking the upper limits of where he has cleaned off the grime. Approximately one third of the 40 units in the city-owned building at 590 Parkside Ave. in Brooklyn are occupied. A fire last November left a 50-square-foothole in the roof that gobbled snow all winter and went unrepaired until May when James Kelly and two other tenants fixed it themselves. There was no heat or hot water for weeks during the cold season …. The intercom has not worked in years. “It’s just patch-up 590,” says Mrs. Kelly, shaking her head and laughing.

1979

Council Eyes Renewed J-51 Plan for Even Bigger Tax Giveaway

By https://citylimits.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/times_square_historic_photo-1.jpg

October

A city program that in 1979 will reward owners who rehabilitate buildings for multi-unit housing with $74.8 million worth of tax exemptions and abatements could be a still bigger giveaway in years to come, if City Hall has its way. But, City Council insurgents have mounted a challenge to the city’s business-as-usual proposal to extend from 12 to 32 years owners’ exemption from increased tax assessments and to swell tax abatements from 90 to 100 per cent of owners’ costs.

1980

A Day in Housing Court

By https://citylimits.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/times_square_historic_photo-1.jpg

November

Stories abound from Housing Court, and terms like, “It’s a riot,” ” … a zoo,” “It’s total chaos” are frequently used to describe it. On the surface, every faction—tenants, landlords, judges, attorneys, community and tenant associations—complain about the court, but few have suggestions for correcting it and many argue, “It might as well stay the same because we have learned to live with it and what will replace it? Do we want to take a chance on something else?”

1981

The Descending Budget Ax

By Tom Robbins

April

Not City Limits' favorite president.

Reagan and his staff have zeroed in on the public-service employment program because, they say, “CETA must be returned to its original purposes” —improving the employability of low income people, something they charge PSE largely fails to do. Their stand is buttressed by a widely held belief among Congressional legislators that the program remains wracked by the abuses that plagued its earlier years when municipalities used the federal job lines as patronage plums and supplemented the federal salaries with large chunks of local money for middle income people. CETA advocates, on the other hand, counter that many of those early problems in the program have been eliminated both through national legislation and local initiative. The program, they say, is today a well-functioning, meaningful and socially useful experience for participants and neighborhoods.

1982

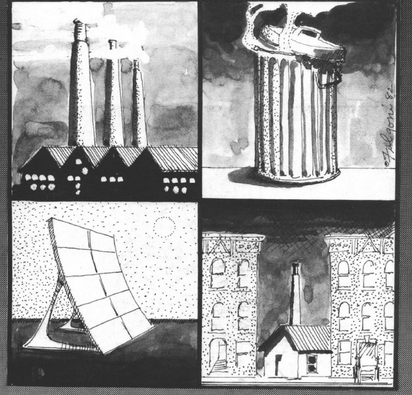

New York’s Energy Future

By Barry Commoner

April

The burden of energy costs on the city’s economy is not evenly borne by its population. The poor and the elderly—people with fixed or falling incomes—suffer most from the escalating cost of energy. Thus, especially for New York, the escalating cost of energy is a viciously destructive force. … It is this dismal outlook that has convinced some that New York, along with other northeastern cities, has outlived its economically useful life and should be allowed to decline.

1983

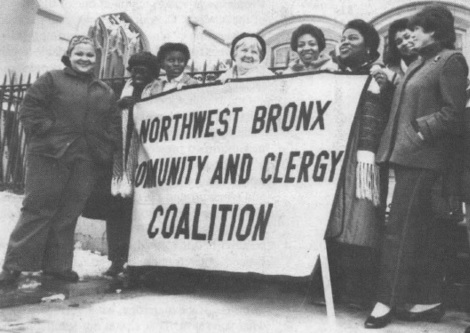

Organizing the Northwest Bronx

By Tim Ledwith

March

The new approach took shape with the birth of a reinvestment committee, composed of [Northwest Bronx Community Clergy] Coalition members from 11 neighborhoods, in 1976. That group started a series of meetings with local lending institutions, armed with the knowledge from Federal mortgage disclosure records that both the number and amounts of loans in the northwest Bronx were declining. At the meetings, community members asked flustered bank and insurance company representatives about their institutions’ reinvestment performance. Unused to the Alinsky-style organizing tactics employed by the Coalition, the lenders first balked at community demands. But by January, 1980, six major financial institutions had been pressed into making concrete commitments.

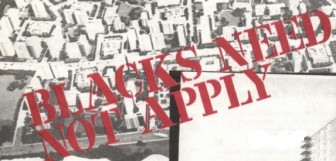

1984

Blacks Need Not Apply

By Nancy Stiefel

October

Starrett City advertised “the good life” in the late seventies, but blacks and other minorities were offered just a 30 percent share of that dream. Management said higher numbers would cause the 6,000-unit project to “tip.” Some rejected black applicants sued, but no trial was held because this spring a tentative settlement was reached. Minorities, however, would still be restricted and the Reagan administration—for its own reasons—has challenged it. Here a former Starrett rental assistant gives the untold story of how Starrett kept minorities out.

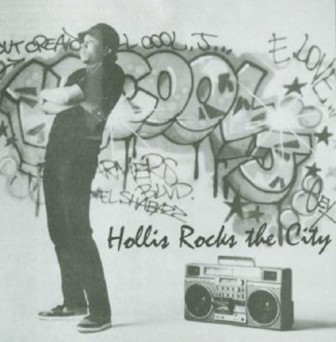

1985

The Hollis Rappers

By Annette Fuentes

December

The Brothers Reeves are part of an illustrious crew of Hillis hometown boys making it in a big way in New York’s rambunctious rap music scene. Over of 205th lives Todd Smith a.k.a. LL Cool J, and Joseph Simmons and Daryl McDaniels live of 209th and 187th respectively. Those two have become more well known as the dapper rapper duo Run DMC. Spyder D, formerly Duane Hughes, grew up in Hollis too, and went to school with Davy DMC. … So much energy, so much talent, so much rapping to come out of one small section of the city.

1986

A Second Chance

By Doug Turetsky

August/September

The devastation was palpable, physically and mentally. An entire community seemed to be in its death throes, with abandoned buildings and littered, vacant lots like scars on a community that was one of the poorest in the city, if not the entire state. Kathleen Casuso remembers that it was impossible to even walk along the sidewalk for fear that a chunk of debris would fall off one of the innumerable deserted, rotting buildings. The Brooklyn community of Bushwick was nearly laid to ruins by years of governmental neglect and bank disinvestment. But two public housing developments have shown there can be a road back from urban decay.

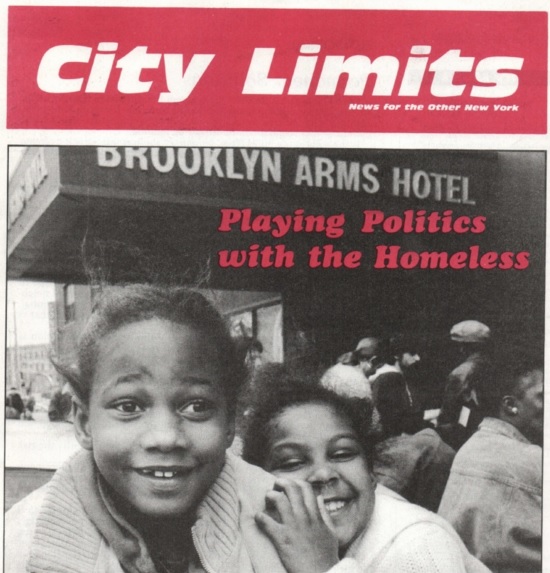

1987

Questions Go Begging in Koch’s Homeless Shelter Plan

by Beverly Cheuvront

May

Last October, Mayor Koch announced a $100 million plan to construct 20 homeless shelters citywide, four per borough. Although his plan met with a barrage of criticism from borough officials, housing advocates, communities and the homeless, he steamrolled his project through the City Planning Commission and is heading full-throttle toward the Board of Estimate. “I don’t suggest any evil intent, but they sure are as inept as hell,” Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins has disparaged the administration’s solutions for homelessness. Robert Hayes, counsel for the Coalition for the Homeless, summed up the mayoral proposal for building large shelters as “stupid.” Curiously, even as the plan speeds ahead, Koch’s aides are tight-lipped about the fiscal and design details of this project. They argue that the mayor’s proposal for large shelters will be cheaper and faster than his opponents’ counterproposals to rehabilitate in rem apartments or construct mini satellite shelters. But they refuse to reveal the basis for their comparison.

1988

Battle for the Beach

By Doug Turetsky

December

For more than two decades a windswept piece of beachfront known as the Arverne Urban Renewal Area has sat vacant. Last month, Mayor Edward Koch announced plans to sell the site—the largest the city owns—for market-rate development. The city’s decision to opt for market-rate housing on the Arverne site dovetailed with the desires of many in the Rockaway area. All the local elected officials, the major civic groups and the community board endorse the decision. But not all local residents believe benefits from the arrival of affluent neighbors —city officials estimate the new residents will need annual incomes of at least $65,000 to afford the new housing —will trickle down to them . “The city is trying to sell us on a plan by saying the market-rate housing will make the area better,” says Maureen Meany. “But we know the trickle-down theory hasn’t worked in the federal government and it hasn’t worked in Atlantic City. “

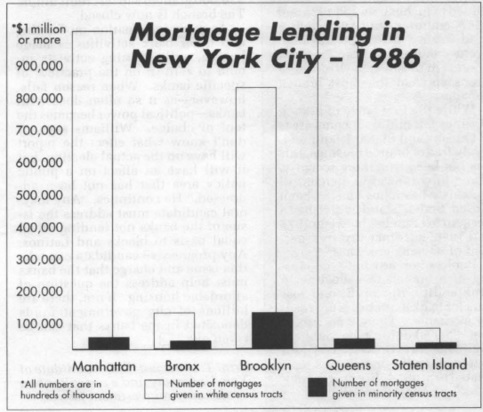

1989

Still Locked Out

By Errol Louis

February

In this election year, there are signs that the issue of community reinvestment may add some extra spark to the usual heat of city politics . For the first time since the fiscal crisis of the mid-1970s, community activists are beginning to put bank policies—the foundation of the financial system—squarely on the public agenda. They’re doing it so forcefully that elected leaders are beginning to notice.

1990

Life in a City-Owned Crack House

By Lisa Glazer

November

Franklin Avenue is a narrow strip of tar in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, and on a blazing summer afternoon it serves as a kind of demarcation zone. On one side of the street are Gwendolyn Smith and her five children, sitting on kitchen chairs they’ve brought down from their apartment. On the other side of the street, leaning against a black metal dumpster, are a handful of drug dealers. “Yo, big-bottie girl,” yells one of the drug dealers from across the street. He picks up an empty glass bottle, throws it in the air, and it smashes on the street. The young men beside him chortle, elbow each other and swagger. Smith tenses her mouth but quickly swallows the insult. She turns her attention toward her four-month old baby, Mydisa, and wipes her face clean. The drug dealers are bored, business is slow and Smith isn’t taking any chances: She lives in the same building the dealers operate from.

1991

Disposable Dreams

By Andrew White

October

All Boro, R2B2 and more than a dozen voluntary dropoff centers across the city are part of a fledgling community recycling network that provides a panoply of economic and environmental benefits. The organizations save the city money by reducing the flow of garbage to the nearly- full Fresh Kills landfill. They offer jobs for unskilled workers in need of steady income. And they give practical recycling experience to residents of neighborhoods across the city. In the wake of draconian budget cuts, this network is now facing extinction. The Department of Sanitation’s recycling funds for the current fiscal year have been slashed from $65.5 million to $11.4 million and all outside contracts with community-based groups have been eliminated.

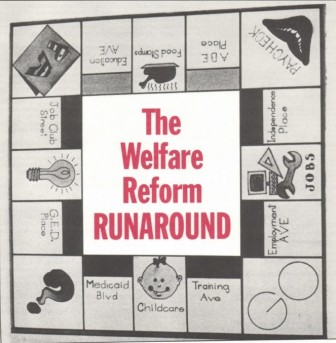

1992

The Welfare Reform Runaround

By Mary Keefe

June/July

On the wall outside Room 401 in the South Bronx welfare office on Rider Avenue is a large, framed illustration of a Monopoly board with a difference. The squares on the board have names like Education Avenue, Independence Place and Employment Avenue. And one corner of the board is home to a large pair of smiling red lips accompanied by a single, tantalizing word: “Paycheck. ” But it’s very doubtful that the women waiting on hard blue plastic chairs inside the welfare office will end up as smiling recipients of a paycheck. They’re part of a historic social experiment called welfare reform-and it already appears to be failing in New York.

1993

Chinatown Portraits

By Peter Kwong

May

Gwen Kinkead devotes one-third of the book to criminal activities, spinning gruesome tales of Chinatown tongs and gangs. Chinese underworld culture and its murderous villains have long kept American readers entertained. Kinkead’s construct of a global Chinese criminal network does not disappoint. She paints the network as a shadow army saturating the U.S. with heroin and smuggled illegal aliens. The sophistication of these criminal elements has supposedly overwhelmed our law enforcement. Kinkead puts the blame on Chinatown residents and their unwillingness to cooperate with police. The problems of Chinatown are American problems. As the U.S. continues its development into a multi-racial society, the false dichotomy-us vs. them-must cease. Kinkead’s time-warp treatment of cultural differences created by circumstance precludes a new societal order of mutual respect and understanding.

Momos

1994

Guilty Until Proven Innocent

By Kim Nauer

November

Some called it a case of mistaken identity. Others said it was perjury. But lying is exactly what the Child Welfare Administration did last July when the agency went to Brooklyn Family Court with a petition to remove Caroline Cappas’ day-old baby from her custody. The baby didn’t exist. …The agency knew Cappas had been pregnant four months earlier. By their watch, she should have had a child by now. So CWA, which had already taken Cappas’ five older children and placed them in foster care, went forward with the removal petition. For good measure, the lawyers invented a sex and birthdate for the nonexistent child.

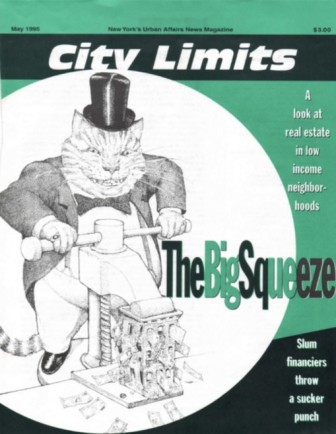

1995

The Big Squeeze

By Andrew White

May

It all began in the early part of the last decade when, after 20 years of devastating owner-abandonment and arson-for-profit, government returned to neglected areas with low-interest financing, replacing windows and boilers, eventually even financing the rehabilitation of entire buildings. Within five years, this public investment helped put a stop to the long decline, recalls former city housing commissioner Felice Michetti. But it also sparked private investment, much of it extremely reckless, as speculators got caught up in the highs of a co-op conversion frenzy they thought would spread from gentrifying middle class areas.

1996

Forty Deuce

By Kierna Mayor Dawsey

August/September

It will all be, at long last, sane—remarkably so. But using my own Brooklyn sensibilities as the barometer, I would venture to say that the new 42nd Street will also prove intimidating, albeit intriguing, to thousands of young people who will grow up here in the Big Apple and perhaps never leave—those city kids who unabashedly wear the oft-misunderstood banner of Black and Latino urban youth culture everywhere they go. I’m afraid they’ll be shut out. Hell, they like Mickey Mouse, too. But I’m very fearful it’s somebody else’s Disneyland

1997

Promises, Promises

By Glenn Thrush

June/July

The anger rising on Southern Boulevard is directed at the New York City Housing Authority, their landlord and, to hear the tenants tell it, their tormentor. Four years ago, most of the residents gave up crowded apartments in housing projects or rundown private housing to take units renovated under the authority’s Multifamily Homeownership Program. … If the promise had been kept, thousands of tenants would own their own places—and the city would have developed an important new program to dispose of its huge backlog of tax-foreclosed apartment houses. It was supposed to be a model of ingenuity and innovation. Promises, promises. [The program] has been almost a complete failure and a study in how a bigfoot bureaucracy can trample a good idea—even given ample money , cream-of-the-crop tenants and the full force of the I990s national bootstrap movement behind it.

1998

7-and-a-half Days

Kevin Heldman

June/July

A nurse comes out into the foyer. She asks me what the problem is. I tell her I’m depressed, I need some help, I don ‘t want to go on living like this, I’m thinking about killing myself. “You use cocaine, huh? Smoke some crack tonight, huh? ” She frames it as a statement, not a question. I say no, I don’t use drugs, I’m just worn out by life, overwhelmed by poverty and stress, sick of going on. Several more times she conspiratorially asks me about the heroin or crack I’ve used. I say no repeatedly. She tells me to pull up my sleeves and looks for track marks.

1999

The Harlem Shuffle

by Kemba Johnson

November

Three years ago,HUD banned for-profit investors from the program, citing problems with profiteering and corruption. Now, City Limits has learned, for-profit interests are once again profiting mightily from the 203(k) program. The result: overpriced properties in poor neighborhoods, quick-flip speculation, and, in Brooklyn, a chain of expensive defaults. ‘This is so big and such a mess, it’ll take [HUD] years to figure this out,” says a HUD official close to the Brooklyn investigation. ”By that time there will be so many [nonprofits] in default.” … The program is supposed to bolster home ownership. Instead, the invasion of the Long Island realties, backed with government money, is pushing housing out of reach—and turning Harlem into a cash machine.

2000

Making Up Kids’ Minds

By Liza Featherstone

July/August

Advocacy groups like the Washington-based Center for Education Reform tout charter schools as a chance for poor families to have control over their children’s education-just as wealthy people already do. The rhetoric of choice goes all the way up the political line. As Governor George Pataki announced when he signed New York’s new law last spring, “Our new charter schools will give parents real choices in education and will provide teachers unprecedented freedom to innovate.” But the law actually works against innovation. Charter schools can’t get public funding for startup costs—which means, most seriously, no money for constructing, renovating or leasing a building .

2001

The New Wage Movement

By Annia Ciezadlo

March 2001

In this city, there are home healthcare aides bathing sick people for $6.55 an hour. There are people making $7.82 an hour to feed and play with children. And then there’s Bertie Caraway, still living from paycheck to paycheck on $7.49 an hour after 26 years of cleaning house, running errands, doing laundry and preparing meals for people too sick to take care of themselves. “Sometimes I get very angry. I think ‘Oh my God, I’ve been doing this all these years, and look at my wages,'” she admits. ”But I keep working, because I care about my clients.” Helpless victims of hardhearted bosses? Just more casualties of corporate greed? Hardly. These workers and more than 100,000 others all work for human-service nonprofits, and the money in their paychecks comes from the city of New York.

2002

Williamsburg Brewhaha

By Matt Pacenza

May

James Maher

“Spectacular East River views, 1 to 7BR,roof gardens, parking, some apts. affordable. Available 2003.” This ad may soon appear in papers across the city as a developer prepares to break ground this spring on Williamsburg’s first waterfront housing development. Slated for the former home of the Schaefer Brewery—which operated along the riverfrom1918 to 1976—the development is a welcome answer to the area’s growing housing crunch. For years, as East Village hipsters priced out of Manhattan have streamed into Brooklyn to find more affordable places to live, Williamsburg’s longtime, lower-income residents have clamored for cheaper apartments. But the city’s choice of one local developer over others has revived some old tensions between the Hasidic and Hispanic communities which observers fear could reverse years of mending.

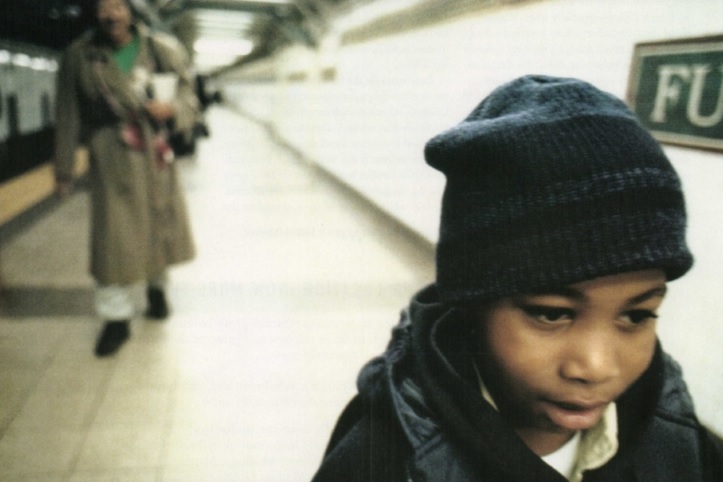

2003

Market Babie

By Tracie McMillan

January

Kwame Boame is only 6 years old, but he’s already got a helluva commute. Every Monday morning, Kwame’s mother, Kimberly Paul, rustles him out the door at 6:30 to take the A train from their apartment in the Dyckman Houses, at the northern tip of Manhattan, to the island’s southern border. In the Broadway-Nassau station, next to the magazine stand on the A platform, they meet Kwame’s great-grandmother, who shepherds Kwame onto the train to Bedford-Stuyvesant, where he goes to school. For the next five days, he’ll stay with his grandmother and great-grandmother. Kwame won’t see his mother again until Friday. Kwame’s weekly commute and bi-borough living are Paul’s response to a common conundrum: a low-income parent’s need to find affordable, quality child care. Almost since the city began building its publicly funded day care for low-income families through its Agency for Child Development in the 1970s,waiting lists have numbered from thousands to tens of thousands. Then came welfare reform.

2004

Will You Adopt Me?

By Kendra Hurley

June

Twelve-year-old Marisol Torres, a round-faced girl with a pink headband, long black hair and thick bangs, sits primly before a room of nearly 50 people at an orientation in Harlem for adults who are thinking of becoming adoptive parents. In a few minutes, Marisol will be videotaped as she tries to persuade this audience that someone out there should become her new mother or father. … At first Marisol deftly whittles the complications of her life to a few charming facts … Then everything goes wrong.

2005

The People’s Mayor?

By Alyssa Katz

July/August

The new Battery Park City deal is a side effect of the administration’s West Side redevelopment mania. In March 2004, the mayor and governor announced an agreement to finance the expansion of the Javits Center, a plan that counted on using $350 million in Battery Park City revenues. That use of the funds was shot down by State Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, and the city never pursued it further. But the Javits flap was a wake-up call to affordable housing advocates: The Battery Park City money was once again in play. The Battery Park City Authority had restructured its debt, freeing $1.1billion in proceeds and generating its final payment to the city under the 1989 agreement.Theslate was clean. And a new alignment of advocacy organizations stepped up to bring the pledge back from the dead.

2006

Dissecting Welfare Stats

By Cassi Feldman

April 17

The mayor grabbed headlines earlier this month when he announced that welfare rolls had dipped to their lowest level in more than 40 years. But new data obtained by City Limits from the Human Resources Administration (HRA) reveals a less impressive trend: Of the recipients who leave welfare each month, only around 23 percent are known to have found work. The rest, according to HRA, just stop showing up for appointments. Meanwhile, a dramatic 67 percent of cases added to the rolls each month are returnees, proof of what advocates call “churning,” the tendency of low-wage workers to cycle between government assistance and dead-end jobs. “Oh God,” said Mark Levitan, senior policy analyst at the Community Service Society (CSS), a research and advocacy group, when he heard the new numbers. “Talk about a revolving door.”

2007

Prisoners Dilemma

By Jarrett Murphy

Fall

Headed to arraignment in Brooklyn.

In an era of falling felony crime rates but rising arrest numbers, New York City’s courts are increasingly dealing with low-level misdemeanor offenses that years ago might never have led to arrest, arraignment and bail. And at the same time, a growing litany of life consequences—the loss of housing, ineligibility for some jobs, disqualification for government assistance—have been arrayed to target people found guilty even of petty crimes and non-criminal violations like disorderly conduct. People who get arrested today are likely to be accused of more minor crimes but face penalties for a conviction that go well beyond prison or probation. Bail can hasten those convictions regardless of guilt or innocence

2008

A Show of Hands

By Ali Winston

March 3

The concerns, however, aren’t confined to privacy issues. CityTime critics like State Assemblyman Alan Maisel (D-59th District, Brooklyn) are worried about the cost of the entire program, which also includes developing a computer network for data transfers. “I have a hard time understanding it,” Maisel says. “There is so much money available for the Mayor’s gadgets.” The CityTime budget from 1999 to date outstrips this year’s proposed budget cuts of $324 million and $95 million for the Department of Education and the NYPD, respectively. Besides the size of the CityTime budget, there are questions about the companies who’ve been contracted under it. … A smaller “quality assurance” contract with Spherion, a Florida consulting firm, has also raised red flags. … OPA chief Bondy launched his own consultancy and worked as a subcontractor for Spherion on CityTime from 2002 to 2004 immediately prior to being hired by the city. Bondy’s biography on the OPA website does not mention this work. Bondy and City Hall maintain that his past employment was brought to the attention of the Conflicts of Interest Board (COIB), and settled appropriately.

2009

A Winter’s Tale

By Karen Loew

March 9

With local unemployment up, home foreclosures continuing, and dire economic indicators as far as the eye can see, the city’s announcement last week that street homelessness is down 30 percent from last year was promptly met with disbelief from some quarters. Merely an hour after the Department of Homeless Services issued its press release Wednesday, the Coalition for the Homeless issued one, too. “The numbers released by the city today defy credibility and run counter to what New Yorkers observe every day on New York&’s streets,” said Coalition Executive Director Mary Brosnahan. “Looked at over a four-year period the city is arguing it has cut street homelessness in half. Do New Yorkers really think there are half as many homeless people on our streets as four years ago?”

Taleen Desrdepanian

2010

Is the Promise Real?

By Helen Zelon

March

There has been some success, no doubt. Canada possesses enormous integrity; his lifelong dedication is unquestioned. But it’s unclear whether the Harlem Children’s Zone is an exportable, adaptable commodity that can work from Cleveland to Compton or a “sui generis,” only-in–New York idea. Not every neighborhood could claim the deep, dense financial and political resources that have nurtured the Harlem Children’s Zone. Not everyone has a homegrown Geoffrey Canada to lead the way. How much does a dynamic, charismatic, visionary leader matter? Short answer: a great deal.

2011

Even Entrepreneurs Need Food Stamps

By Neil de Mause

July 12

Marc Fader

Tanya Fields at home, at work.

It’s Monday, Jan. 31, and as usual, Tanya Fields is having a hectic morning. The Bronx mother of four has already had to juggle her schedule after her babysitter called in sick, forcing her to be late for an important appointment in downtown Brooklyn. But on this occasion—unlike her daily work running a nonprofit start-up or her prior years as an environmental advocate—there’s no calling in sick or asking to reschedule: This appointment is for trying to keep her welfare benefits.

2012

Years of Warnings, Then a Boy’s Death

By Jordan Moss

March 13

Building blazes that kill kids usually burn as brightly the next morning in the tabloids. But the fire that took 8-year-old Jashawn Parker in the late evening of Aug. 6, 2002, on a typically dense northwest-Bronx block somehow never got much ink—just a couple brief stories in the Daily News and a small item in the Post. It’s unclear why. The fire stemmed from a hyperdocumented virtual time bomb that tenants and advocates had worked to defuse for two years. The six-story building at 3569 DeKalb Avenue, just off Jerome Avenue and next to Woodlawn Cemetery, was a stunning case study of the city’s flawed housing-code enforcement system, with the scope of dangerous neglect apparent to anyone with an Internet connection. At the time of the fire it had 387 code violations, with leaks, water damage, electrical problems, roaches and mice among them. At least two Housing Court judges cut the building’s landlords slack rather than appoint an outside administrator, despite minimal signs of repair progress.

2013

Campaigns Skip Mott Haven, Drug Centers and Shelters Don’t

By Joe Hirsch

March 26

It was standing room only on a Saturday afternoon in March at a South Bronx church known for its social activism streak, where residents came, hoping to hear the city’s mayoral candidates explain their positions on the issues. There was only one problem: The three candidates considered frontrunners in next November’s election—City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, Public Advocate Bill de Blasio and former Comptroller Bill Thompson—were nowhere to be found. Many expressed anger that Quinn, de Blasio and Thompson had ignored invitations to attend, saying it was an indication of the low regard in which the city’s power structure holds the South Bronx. “I don’t know about you, but right now, I’m pissed off,” Pastor Kahli Mootoo of Bright Temple AME Church in Hunts Point bellowed into the mic, to sustained applause. “For them not to be here, I’m pissed off so bad, Monday morning I’m going to pick up the phone and I’m going to make some phone calls.”

2014

For Clients Sick or Not, Hospitals Serve as Safe Havens

By Ruth Ford

March 13

People come to hospital emergency rooms to sleep, to sober up, to get warm, to stay in between other shelters. They come if someone is violent at home, or back on drugs, or if they’ve lost their job. “As long as they’re not disruptive, there’s no reason to think something else is going on,” says one hospital administrator, who requested anonymity. “There are certain circumstances where you do pay attention: Someone comes in with a family, sits down there for three or four hours.” Then, something needs to be done. But for the most part, people use it as a quick stay, to “sober up, sleep” and then move on.

2015

Closing Rikers

By Ed Morales

November 25

Certainly there is plenty in the air about criminal justice reform – not just in New York but all around the country – particularly since the anguished summer of civilian deaths at the hands of police in Ferguson and Staten Island last year, the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement … Whether that heightened awareness translates into a death sentence for Rikers depends not just on the politics of closing down one of the largest correctional facilities in country, but on elected officials’ ability to come up with something to replace it.