NYCEDC

The city held its first public meeting Wednesday about the future development of Sunnyside Yards.

The city held its first public meeting Wednesday night about the future development of Sunnyside Yards, an active 180-acre rail yard in western Queens which officials say could be decked over to create a potential site for new housing, schools, parks and other needed infrastructure—though some community members say they’re worried about the impact such a massive project could have on surrounding neighborhoods.

The meeting, which took place at LaGuardia Community College, aimed to engage residents in the city’s “master planning” process, which will create a long-term plan for how Sunnyside Yards could be developed over the next several decades. The railyard, nestled between Long Island City and Sunnyside, is currently used by both Amtrak and the Long Island Railroad (LIRR). It represents a rare opportunity as one of the few remaining large parcels of undeveloped land in the city, officials said.

“It’s an exercise in dreaming big,” Carl Rodrigues, a senior policy adviser to Deputy Mayor for Housing and Economic Development Alicia Glen, told attendees Wednesday night. “The idea here is to set up a foundational plan for future generations of New Yorkers.”

While the idea of building over Sunnyside Yards had been floated before, Mayor Bill de Blasio first announced his vision for the site during his “State of the City” address in 2015, saying the space would allow the city to build thousands of new units of affordable housing. A feasibility study published by the city’s Economic Development Corporation last year estimated the rail yard could accommodate between 14,000 and 24,000 new housing units—4,200 to 7,200 of them affordable—as well as new parks, schools and retail.

But at Wednesday’s meeting, officials stressed that nothing has been decided yet for the site, and that it will take decades before any actual development takes place.

“We are not walking into this effort with any predetermined program, or a plan that’s already made,” Rodrigues said. “We are committed to listening.”

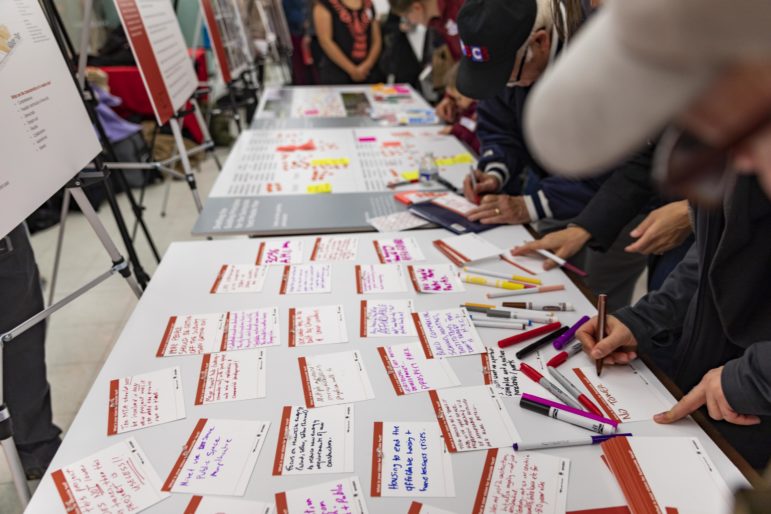

The event was less a traditional public meeting and more of an open house, with five different interactive stations set up around the room where residents could ask questions and share ideas. One station asked attendees to fill out index cards describing their “vision” for Sunnyside Yards and pin them to a large poster board; another allowed visitors to scrawl their ideas and concerns for western Queens on sticky notes, which were put on display for others to read.

Many of the messages mentioned the need for more parks and green space, while others—likely written by the number of union workers who were in attendance—called for any development of the site to be done using organized labor. “No more high rises,” one note read, while another message asked for community centers, youth centers and “no gentrifiers.”

NYCEDC

Attendees were asked to write down their ideas for Sunnyside Yards.

The notes echoed concerns expressed last year by community advocates who worry that developing the rail yards could lead to the displacement of longtime Queens residents.

“We cannot create housing and displace the people around it. That’s probably my biggest concern,” said Melissa Orlando, founder of the transit advocacy group Access Queens and a member of the Sunnyside Yard Steering Committee, a team of local stakeholders asked to advise the EDC during the planning process.

She said that while “we absolutely need more affordable housing in Queens,” she’s wary of how the city currently defines affordability under de Blasio’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program, saying the rent-restricted units created so far by the initiative are still unaffordable for many residents.

Orlando also wants to ensure any development of the site would include new transportation options, since local subway lines like the 7 train are already overcrowded.

“We’re worried about the L train shutdown, which is going to bring … a couple of thousand people here. I don’t think anyone’s going to be able to get on the 7,” she said. “So to create this whole new neighborhood—there has to be adequate transportation.”

Brent O’Leary, president of the Hunters Point Civic Association, expressed similar concerns, saying the area’s existing parks, schools and transit lines are already overburdened.

“We don’t have the infrastructure to support the people that are here right now,” he said. “How can you put another city between Long Island City and Sunnyside? It will drown us.”

Others, however, see Sunnyside Yard as an opportunity. Victor Salazar, a longtime yellow cab driver and member of the Taxi Workers Alliance, thinks future development at the site could make it a popular taxi pickup and dropoff site, considering its proximity to Manhattan and the 59th Street Bridge.

He also suggested that a portion of affordable housing at the railyard, if it’s built, be set aside specifically for cab drivers, many of whom are struggling to make a living as the rise of the for-hire vehicle industry has cut into their profits.

“I used to live in Long Island City because it was convenient for me as a taxi driver, close to the city, and because the taxi fleets are around here. But now I moved to the Bronx because it’s so expensive to live nearby,” Salazar explained. “We would love to have consideration.”

For those who missed Wednesday’s event, fear not—officials say there will be plenty of additional chances for people to express their views on the project, with plans to hold future meetings, workshops and site tours, according to Sunnyside Yards Director Cali Williams.

“This is the first of many opportunities,” she said.

3 thoughts on “First Meeting on Future of Sunnyside Yards Finds Some Wary of Overdevelopment”

Pingback: WHAT'S WRONG WITH RETAIL IN LONG ISLAND CITY? | LICtalk

What makes anyone think Amtrak and the MTA is going to let anyone build over their rail yards, which would mean eliminating some of the tracks used to store engines and passenger cars.

Probably the fact that Hudson Yards in Chelsea was pretty successful.