Why has the number of homeless New Yorkers grown so much, even as the city spends billions on housing and homeless services? One part of the answer is that over four decades there has been an ongoing and fundamental disconnect between the city’s policies on homelessness and housing.

Adi Talwar

New Yorkers experiencing homelessness who were camping out on a Lower Manhattan sidewalk near Tompkins Square Park until the city cleared the site during a “clean up” on Nov. 10.It’s been more than 40 years since the issue of homelessness thrust its way into New Yorkers’ consciousness. Since then, homelessness has only increased.

On a recent January night, more than 45,000 people slept in a city Department of Homeless Services shelter—a population large enough to rank among the 20 largest cities in the state. Among those in the shelter were nearly 8,400 families with about 14,500 children. (These numbers don’t include thousands of other New Yorkers in domestic violence and other shelters administered by other city agencies). Turn back the clock by about four decades to the end of 1983, when there was a total of 14,855 people in New York’s shelters—about a third of today’s—including roughly 2,100 families and 6,230 children, according to the Coalition for the Homeless.

This exponential growth in the number of adults and children in shelters occurred despite substantial city spending on homelessness and housing. The city now spends about $3 billion annually on services for the homeless through a variety of city agencies, up from about $880 million 20 years ago. At the same time, the city has implemented a series of multibillion dollar “affordable” housing programs. Former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s 12-year housing plan earmarks $16.9 billion to create and preserve 300,000 apartments. That’s on top of billions spent by previous mayoral administrations, beginning with the Koch administration’s $4.2 billion 10-year plan (later increased to $5.1 billion), which launched in 1986 and ultimately created and preserved about 150,000 units.

Given all this spending and housing production, why has the number of homeless New Yorkers grown so much over the years? One part of the answer is that over the four decades there has been an ongoing and fundamental disconnect between the city’s policies on homelessness and housing, explains Ellen Baxter, who along with Kim Hopper wrote an influential report on homeless adults in 1981 and has since gone on to develop permanent homes for unhoused individuals and families, most recently as the founder and executive director of Broadway Housing Communities.

This disconnect became more striking under de Blasio, who can tout record housing production while the number of people in the city’s shelter system has also soared to record levels, explains Jacquelyn Simone, senior policy analyst at the Coalition for the Homeless. The discrepancy stems from interrelated factors, from funding to ideology, that have propelled this disconnect over the decades.

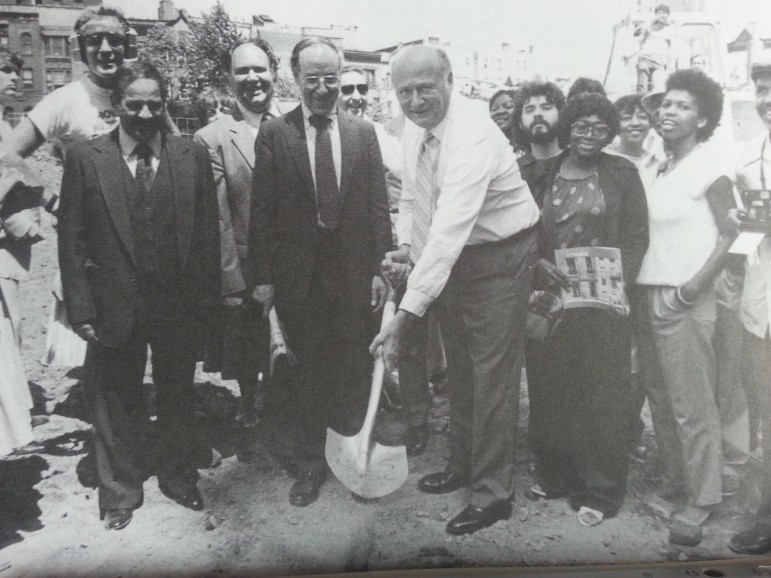

City Limits archives

Just a little over 10 percent of the 150,860 apartments created or preserved in 1986 through 1996 under the Koch administration’s plan went to the homeless.

A split that started with Koch

Mayor Koch’s 10-year housing plan set the template for affordable housing development by the city for the ensuing decades. Up until then, housing for lower income residents—in New York and across the country—was largely seen as the responsibility of the federal government. But that changed with President Ronald Reagan, who gutted many national housing programs. Koch faced a variety of housing-related issues, and limited resources to address them without much help from Washington. Likewise, the plan also reinforced the bureaucratic separation of the city’s public housing developments, home to more than 400,000 lower-income New Yorkers, from other city-sponsored housing programs or initiatives.

Part of the city’s legacy from the 1970s was thousands of abandoned and tax-foreclosed buildings, many of them vacant. In the 1980s, as the city recovered from its near fiscal collapse, housing prices rose, but for many New Yorkers income continued to lag. Roughly half of all New York City renters were paying more than 30 percent of their income—the general guideline for affordability—for rent.

“New York City is entering into a new era of growth. Decent, affordable housing is essential to that growth,” said Koch when he first unveiled his housing plan. While he highlighted the growing number of unhoused on the city’s streets and sheltered in hotels as “[T]he most poignant indication of the severity of the housing shortage,” it wasn’t until page 19 of the 22-page speech that he focused on the needs of the homeless. And the goal was relatively modest: increasing the number of subsidized apartments for the homeless by 1,000 a year to 4,000. Yet as Koch himself noted, roughly 47,000 individuals and families were doubled up, sleeping in the homes of friends or relatives, along with the thousands in the city’s shelters.

Given the lack of affordable apartments for a wide swath of New Yorkers, the proliferation of abandoned buildings and vacant land in many neighborhoods and the relatively limited city funds available, the Koch plan heavily relied on the for-profit sector to develop needed housing. Creating apartments for the poorest New Yorkers required very deep subsidies—as it still does today—and the Koch administration sought to maximize production numbers. And for-profit developers never had much interest in building housing for the poor anyway.

Despite the pressing need for homes for the unhoused, just a little over 10 percent of the 150,860 apartments created or preserved in 1986 through 1996 under the Koch plan went to the homeless, according to data compiled by New School professor Alex Schwartz. Nearly three-quarters of the apartments in newly constructed buildings went to middle-income households.

Some of that mismatch may have been encouraged by the strictures of federal funding, which served as “an incentive to shelter rather than house,” says Victor Bach, senior housing policy analyst at the Community Service Society of New York (a City Limits funder). While the cost of sheltering a family in a hotel room was about $2,000 a month in the early 1990s, half the tab was picked up by Washington, and another quarter by the state. From a fiscal perspective it wasn’t a priority to move families out of the hotels. Nor was it legally—court orders won by advocates for the homeless only required the city to provide shelter, not homes.

Another likely factor was public attitudes. Many voters, and elected officials, were loath to provide assistance to the “undeserving poor.” During the 1980s and 1990s, the ideology of personal responsibility was in ascension. “There’s a tendency to pathologize poverty and to blame people for their lack of housing,” says Simone.

Yet housing costs are frequently at the core of homelessness. In The Bronx, the poorest county in the city, a worker earning the borough’s typical wage would have to work 66 hours a week to afford a one-bedroom apartment at fair market rent, according to statistics compiled by the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

While a national 2017 Yale University study found that attitudes had shifted since the 1990s and homelessness was increasingly seen as attributable to external factors, that doesn’t mean the public was ready to focus resources on those most in need. A March 2021 poll conducted for the Citizens Housing and Planning Council found that among New York City voters, 3 out of 5 thought that housing and homelessness were major issues, but only 31 percent thought the city’s efforts to build affordable housing should be centered on the poorest or most vulnerable.

Federal dollars, or the lack of them, and public attitudes have continued to contribute to the disconnect between the city’s housing and homelessness policies. The Dinkins and Giuliani administrations finished Koch’s 10-year plan without much change in approach. For Dinkins it was largely a matter of a recession and lack of resources, although he did prioritize reserving some vacancies in public housing for people in the city’s shelter system. The Giuliani administration largely emphasized a punitive approach to poverty and homelessness, with a greater focus on creating hurdles to assistance than producing housing affordable to the poorest New Yorkers. That the composition of the city’s homeless population is predominantly Black and Latinx may have been a factor in this approach—a recent estimate put the share at nearly 90 percent.

New mayors, new plans

Mayor Michael Bloomberg put a renewed effort into affordable housing construction with his own 10-year initiative to create and preserve 165,000 apartments, called appropriately enough the New Housing Marketplace Plan. But this marketplace was largely aimed beyond affordability levels for the homeless and other very low-income New Yorkers. Much of the roughly 45,000 newly constructed apartments built under the plan were affordable only to households with incomes about double the federal poverty level, according to a 2014 Community Service Society report.

In 2004, Bloomberg announced the ambitious goal of cutting the homeless population by two-thirds in five years. Instead, homelessness grew to then-record levels over his 12-year mayoralty, with the number of people sleeping in city shelters increasing by 71 percent, according to the Coalition for the Homeless.

Falling far short of his goal, Bloomberg looked to shift blame elsewhere and disingenuously proclaimed, “You can arrive in your private jet at Kennedy Airport, take a private limousine and go straight to the shelter system and walk in the door and we’ve got to give you shelter.” In fact, one of the reasons the shelter population grew was because the Bloomberg administration stopped prioritizing homeless families for federal rental assistance, or at least what rental assistance existed—nationally, there’s only enough funding for about 1 in 4 of the households that qualify. Additionally, in a budget spat with then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Bloomberg eliminated the city’s own rental subsidy.

Mayor de Blasio, elected on a “tale of two cities” theme, seemed poised to challenge the ongoing dynamic and tilt the city’s housing efforts towards the needs of the unhoused and those most in need. But de Blasio wanted to produce big numbers of units, proposing first a 10-year plan to create or preserve 200,000 apartments, and then upping the ante to 300,000 over 12 years.

A January 2021 report from the Community Service Society aptly sums up the results so far (the plan runs to 2026): “…the administration has prioritized achieving its chosen metrics without ensuring those metrics address the city’s actually existing affordability crisis. In fact, the act of chasing large quantities of the wrong metrics incentivized the administration to prioritize plans and programs…that produced the greatest numbers of units with a given amount of investment, or those most favored by the private developers and investors upon which their plans relied rather than those which would have met the greatest need.”

Over the years 2014-2018, for-profit developers built more than 70 percent of the newly constructed apartments under the de Blasio administration’s housing plan, according to the Community Service Society report. But only 18 percent of the apartments produced were affordable to extremely low-income families. Conversely, 35 percent of the apartments developed by nonprofits were affordable to families with extremely low incomes.

While de Blasio’s housing production and preservation plan may not have been focused on the unhoused and those most vulnerable to homelessness, his administration has taken other steps to directly aid them. These include a new rental assistance program to help families leave the shelter system, a restoration of the priority for homeless families when apartments become vacant in public housing, expansion of so-called one-shot deals to help families pay back rent and the provision of legal assistance for low-income tenants in housing court.

These efforts have contributed to bringing down the number of homeless families in the shelter system since the peak in 2017—though the number of single adults in the system has continued to rise. Yet probably the biggest factor in the recent decline has been the pandemic-related moratorium on evictions, which stemmed the number of families coming into the system as the de Blasio administration has helped others leave. But the moratorium expired on Jan. 15, just two weeks after Eric Adams became mayor.

Much of Adams’s post-election statements have focused on public safety and making New York City more business friendly. And in the days since taking office, the Covid pandemic and several high profile crimes—including two NYPD officers who were shot and killed while in the line of duty—have absorbed much of his attention. A joint proposal between the mayor and Gov. Kathy Hochul will flood the subways with more police officers, though the officials have pledged to utilize trained social workers to do the bulk of homelessness outreach underground.

David Brand

Eric Adams announced his plan to convert struggling hotels into homeless housing in Brooklyn in September.

When it comes to housing, his campaign website listed proposals such as increasing rental subsidies to prevent homelessness, creating land trusts and giving vacant sites to organizations committed to providing permanently affordable housing, and converting vacant hotels and office buildings to housing. But the details behind these initiatives—such as the affordability levels of the housing and how deep the public subsidies might go—remain to be seen, and may fall prey to the influence of the new mayor’s high-dollar donors, including hedge-fund billionaire Steven A. Cohen and a coterie of real estate developers and their family members.

In a recent Daily News op-ed, Richard Buery, a former deputy mayor in the de Blasio administration who now leads the Robin Hood Foundation, implicitly cited the long-running disconnect between the city’s housing and homelessness policies when he urged the allocation of $4 billion annually “to restore public housing and build new units for extremely low-income New Yorkers.”

While funding is of course a key element, a broad coalition of advocates for homeless individuals and families and housing providers urged the new mayor to bridge the policy disconnect by appointing a deputy mayor to oversee both housing and homelessness policies, and eliminate the silos in which various city agencies—from the Department of Housing and Preservation (HPD) to the homeless services department to the public housing authority and others—have operated for years. Mayor Adams has met them halfway, appointing Jessica Katz as housing policy officer to oversee various agencies, including HPD and NYCHA, though her portfolio doesn’t appear to include the Department of Homeless Services.

While the change may improve coordination among the city’s multiple housing-related agencies, an administrative change alone won’t stem homelessness nor ensure that the Adams administration directs resources to build more affordable housing for the poorest New Yorkers.

Doug Turetsky, a former City Limits reporter and editor, was most recently chief of staff and communications director at the New York City Independent Budget Office.

5 thoughts on “Analysis: NYC’s Decades of Disconnect on Housing and Homelessness”

The fastest, and I think most affordable, way to quickly house the chronic homeless, most of which are mentally ill, is for the city to buy up as many old hotels in every borough, and make them “Full Service” homeless housing.

These folks have to have full wrap around services in order to get them to a sane place so they can function in society. Many can’t be “cured” or even leveled out. They need to be placed in appropriate mental health facilities for their own safety and the safety of others.

Many can be helped just by providing a safe, clean place for them to live so that services can be provided. Doing minor fix ups to existing old hotels (to ensure they are safe and clean) would certainly put a big dent in the problem with out the decades long delays any type of new construction apartments would take. The money used to buying the hotels by the city would go a lot further and help more people.

NYC can’t continue to drain the NYC middle-class taxpayer by spending billions on housing for the homeless, and continue to target middle-class neighborhoods for ruin with homeless shelters. The city had better start paying attention to the middle-class before it’s too late. NYC homeowners’ property taxes go up every year just so the money can be flushed down the toilet on ‘housing’ programs and NYCHA.

The goal of converting vacant motels/hotels to permanently affordable housing is a sound one and should be undertaken. I totally agree that many homeless need support services and not just housing in order to have a chance of a more normal life.

However, one of the most expensive and problematic issues is NYCHA. The internal corruption and massive waste of taxpayers dollars is appalling. The maintenance cost per unit in a NYCHA property is nearly as high as many luxury buildings and double the average maintenance cost of other affordable units in the city.

While the rationale is the buildings are old, when you look at the lack of completion of maintenance requests and sadly the fixes often done it is due to lack of the work being performed correctly or scheduling maintenance when no one is home yet counting that as completed work order is mind numbing.

The issues within NYCHA have been documented time and time again by DOI and internal management but never addressed. NYCHA is a problem which no politician wants to truly correct for fear of the powerful unions who control the workforce or the possible anger of the tenants. Someone needs to step up and make the hard decisions, just throwing more taxpayers money at NYCHA is not the answer. The belief that the Feds will pump the estimated $40 billion needed to address the physical needs is simply a pipe dream.

If we assume (maybe wrongly, I’m no expert) for the sake of conversation that the amount public funding toward affordable housing and addressing homelessness is a function of the tax-paying public’s appetite for solutions to these issues, and in any given period of time is relatively fixed, then I would say it’s not quite fair to critique recent mayoral administration’s efforts toward addressing homelessness versus addressing affordable housing for lower income earners of lesser need. Simply, it’s a trade off: there are limited dollars for an almost endless need, on both fronts. We can say “we haven’t done enough to address homelessness” but what about the tens of thousands of families of lesser (but perhaps not extreme low income) means who are now housed in modern, newly-constructed affordable housing buildings built during the Bloomberg and De Blasio admins? Where is their voice? Those are generational life-changing success stories, and there are many. WhT about the neighborhoods that for many decades were scarred by vacant lots and low investment, now being filled-in by beautiful new (affordable) housing buildings by private sector developers, stitching together communities and adding new services and pedestrian foot traffic? Those are success stories. Hard truth: I imagine many of those communities would be loathe to imagine some of those lots having been developed with shelters that, yes, house needy homeless families but also may house mentally ill single men who aren’t exactly adding much positive to the neighborhood dynamic. This article glosses over the victories those affordable housing plans have had, the positive impact they’ve had on neighborhoods, and the collective positive momentum they’ve created in communities. Of course homelessness is a problem, and a problem getting worse with time, but John Q. Public has only so much appetite for dealing with low income housing generally and maybe given a choice they’re just fine with where the priorities have been laid. Just my two cents.

Governments the others organizations paid to solve the homeless problem, but me and the thousands have been living in the streets for years, we can’t find a law or anything. Why go to Shelter living with criminals or people with contagious diseases?

This my story to became homeless in New york >>

https://nnewwwsss.blogspot.com/2022/01/be-quite.html