Adi Talwar

535 Carlton devotes 50 percent of its apartments to upper-middle-income households, with rents set at 160 percent of Area Median Income, or up to $149,490 for a family of four.

In a city where so many struggle for shelter, applicants swamp affordable housing lotteries.

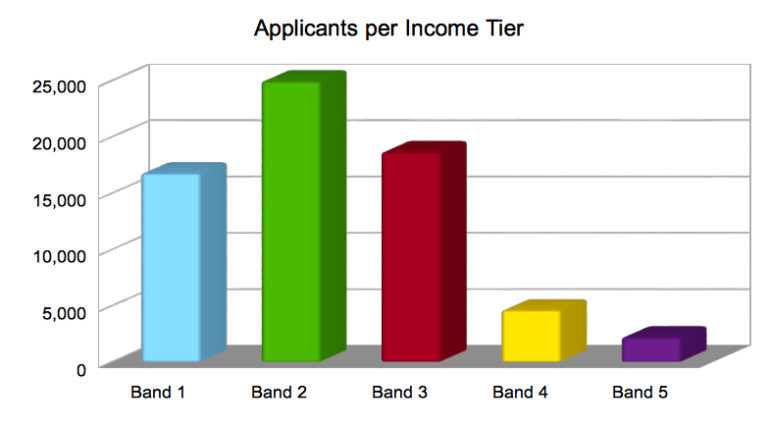

In a January press message, the developers of Pacific Park Brooklyn suggested “the demand for affordable housing in the borough is tremendous,” citing more than 84,000 applications for 181 units at 461 Dean and “roughly 95,000 applications” for 297 apartments at 535 Carlton. These are among the first four residential buildings in the 15-tower project, which will contain 2,250 below-market units among 6,430 apartments in Prospect Heights.

But such catch-all statistics—regularly used in depicting the hunt for below-market units—camouflage how low-income applicants face crushing odds compared to middle-income ones.

Exactly 92,743 households (not quite 95,000) entered the lottery for the “100 percent affordable” 535 Carlton tower, city data show. But only 2,203, according to City Limits’ analysis, were eligible for 148 middle-income apartments, such as one-bedrooms renting for $2,680 monthly and two-bedrooms at $3,223, affordable to those earning six figures. (The massive Excel spreadsheets, with names redacted, were obtained via a Freedom of Information Law request.)

Also, 4,609 entrants vied for 44 units in the building’s other middle-income “band,” which includes one-bedrooms at $2,170 and two-bedrooms at $2,611, with rents set at approximately 30 percent of household income.

For less costly apartments, the competition was fierce. For the 15 moderate-income units, including seven one-bedrooms at $1,320, some 18,680 households applied.

More starkly, nearly 67,000 households, some 72 percent of the applicant pool, aimed at the 90 low-income units, including one-bedrooms at $589 and $929, for singles earning $21,566 to $25,400 and $33,223 to $38,100, respectively.

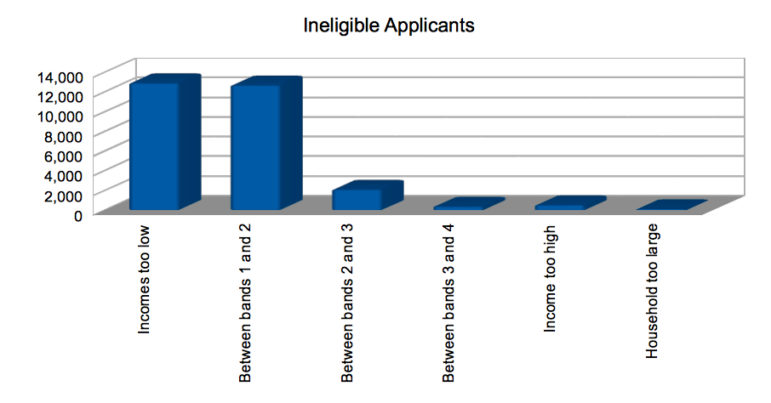

A good number of them were ineligible because their incomes either were too low or they fell between the two low-income “bands.” Also, 15 low-income units will ultimately be distributed outside the lottery, designated for homeless households under a new city policy.

At nearby 461 Dean, which has half market-rate and half affordable units, the lottery pool was nearly as skewed, according to City Limits’ analysis, though the below-market apartments were spread more evenly among households of varied incomes.

Murphy chart/Oder analysis/HDC data

Band 1 includes 3,000 applicants whose incomes would have been too low but for housing vouchers that they brought with them.

This granular analysis challenges simplistic reports about big numbers in housing lotteries. The desperation for low rent insures that any building containing low-income units will generate a robust response, especially since the online NYC Housing Connect system—now with 1 million registered users—makes it easy to apply.

“The results fit with what low-income advocates have been saying: the real need is for the lowest-rent units,” observed housing policy analyst Tom Waters of the Community Service Society upon being told of the findings. Thus, he said, the term “affordable for whom” has growing resonance.

The New York City Housing Development Corporation, which financed the affordable units, did not see reason for concern in the lottery response, given the number of factors that can affect applications to any particular lottery.

But Ismene Speliotis, Executive Director of Mutual Housing Association of NY (MHANY) Management, which manages the affordable housing process for Pacific Park, says the pattern indicates a mismatch.

“Not to say that people in those higher bands aren’t looking for apartments,” said Speliotis, “[but] there’s a disconnect between the population’s need and the apartment distribution.”

Aiming at “affordable”

The results suggest that, aiming to hit affordable benchmarks for the controversial—and delayed—Pacific Park (formerly Atlantic Yards) plan, and to achieve the mayor’s numeric goals, public officials, the developer, and some advocates have hailed middle-income housing for which there’s relatively less need.

Atlantic Yards, announced in 2003, approved in 2006 and then revised in 2009, had long been estimated to take 10 years to build. The rental apartments were to be in towers mixing half affordable and half market-rate units, according to a 2005 agreement original developer Forest City Ratner signed with New York ACORN.

In 2010, however, New York State extended the project deadline to 2035. Given gentrification in and around Prospect Heights, some advocates argued, African-Americans would be priced out during a delayed buildout and thus lose their shot at the 50 percent community preference in housing lotteries. (A subsequent article will look at the demographics of community preference.)

Facing a threatened lawsuit on fair-housing grounds, the city and developer Greenland Forest City Partners—the successor to original developer Forest City Ratner—agreed in June 2014 to a new 2025 deadline for all below-market units and to soon start two “100 percent affordable” rental buildings: 535 Carlton and 38 Sixth.

At the time, Mayor de Blasio told the New York Times, “And what’s remarkable is that we’ve secured nearly twice as many affordable units”—compared to 461 Dean—”for our city investment.” He didn’t say that affordability would differ dramatically.

535 Carlton and 38 Sixth (which is nearing completion) have 50 percent upper-middle-income apartments, with rents set at 160 percent of Area Median Income, or AMI, for households with incomes up to 165 percent of AMI. So a four-person household seeking a two-bedroom apartment can earn $111,909 to $149,490.

By contrast, the initial Atlantic Yards plan designated just 20 percent of affordable units for the highest band, with rents set at 150 percent (and incomes up to 160 percent of AMI). The two new buildings do have more family-sized units than 461 Dean, which had been criticized for emphasizing smaller apartments.

A new middle-income program

When the deal was announced in 2014, it wasn’t clear that 535 Carlton and 38 Sixth would be associated with an emerging 100 percent affordable housing program, M2 focusing on middle-income households. As floated in de Blasio’s June 2014 plan, M2 would include 20 percent low-income units, 30 percent of units for moderate-income ones, and the rest middle-income apartments with rents set at 130 percent of AMI.

Murphy chart/Oder analysis/HDC data

Many thousands of applicants never had even a slim chance of getting an apartment.

Later, M2 was tweaked to allow units with rents above 130 percent AMI, but denying them subsidy beyond tax-exempt bonds. (Thus, de Blasio could say “nearly twice as many affordable units for our city investment.”)

“The middle-income units, which do not receive [direct] subsidy, contribute to the long-term financial viability of the development,” said Stephanie Mavronicolas, director of external affairs for HDC, “while meeting a genuine need for middle income households finding it harder to afford to stay in New York City.”

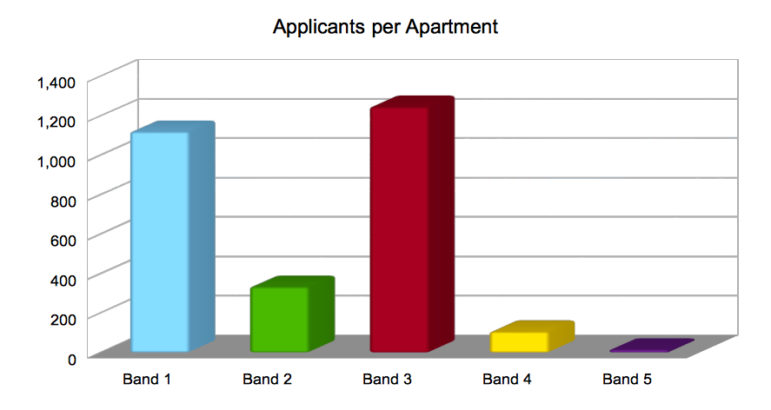

While higher rents surely help the bottom line, the lottery analysis complicates the issue of need. Notably, for 44 two-bedroom apartments renting at $3,223 a month, only 360 households initially qualified. Given that half of 535 Carlton’s units are designated for residents from nearby Community Districts, the 111 applicants with that preference seemingly had a one-in-five chance for 22 apartments.

Such middle-income households, defined by the mayor’s 2014 housing plan as at 121 percent to 165 percent of AMI, are eligible for nearly two-thirds of the units at 535 Carlton and 38 Sixth, though they represent less than 10 percent of the city’s population.

Looking at city policy, some have questioned a middle-income focus. Moses Gates, Director, Community Planning and Design for the Regional Plan Association, recently argued in Crain’s New York Business that such middle-income households “have ample options in New York’s rental market” but rather lack “a supply of homes to buy in their price range.”

In the rental market, that means they outbid lower-income households and drive up rents. “We’re talking about $2,800 to $3,200 [a month] rental apartments,” Gates added in an interview. “That’s something that a healthy market should be producing.”

In studying rent-burdened households, NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy didn’t even look at middle-income ones (though the Citizens Budget Commission did find a smaller fraction of middle-income households were rent-burdened).

Reflecting on the lottery process, Speliotis said it was “really tough” to lease middle-income units, because lottery winners—some of whom may pay below 30 percent of their income right now—have more options than their lower-income counterparts. Some are wary of disclosing their financial information or prefer apartments larger than those produced under new city design guidelines for subsidized buildings.

“It’s important you try things and say, ‘OK this isn’t working the way I hoped. Maybe we should adjust,'” Speliotis observed. “I hope that’s a conversation we can have with the city, and not just on Atlantic Yards.”

A shifting picture

Defenders of the de Blasio approach—targeting a broad range of income bands, including some that struggle less—suggest a long view. In January, when a reporter pointed out that studios at 535 Carlton would actually cost more than one market-rate unit at 461 Dean, Pacific Park’s first hybrid market/affordable building, de Blasio cited the value of rent stabilization for such affordable units, adding that the “market does not offer any such guarantee.”

When the M2 plan surfaced, Gates, then of the Association of Neighborhood and Housing Development, expressed caution, saying that if it was used to replace partly-affordable buildings in gentrifying areas it could be a plus, but if it substituted for 100 percent affordable developments, then the impact would “be questionable.”

In this case, while 535 Carlton and 38 Sixth clearly offer more affordability than developments like 461 Dean that mixed market-rate with income-targeted units, the bigger picture looks different for housing that, according to the Atlantic Yards Community Benefits Agreement, was aimed “to stem the growing trend of displacement through gentrification in Brooklyn.”

The decision to build 100 percent affordable towers—thus frontloading below-market units—enables two future 100 percent market rental towers to be built in Pacific Park, instead of previously planned buildings mixing market-rate and-affordable units.

“There’s a lot more units in the lower band that need to be built,” said Speliotis, who noted that the developer is well aware of that need. “We’re very clear of the commitment and the obligation and we’re keeping track.”

Was this a model?

At the 535 Carlton groundbreaking Dec. 15, 2014, de Blasio said. “To me, this is exactly what we came here to do: 298 units, all affordable,” he declared. “This is a symbol of what we intend to do with our affordable housing plan over and over and over and over.” He deflected this reporter’s questions about why the tower would contain far more middle-income apartments than originally promised.

In the press release, officials and advocates joined in. “The local community desperately needs access to affordable housing and this is a meaningful step forward,” said Michelle de la Uz, Executive Director of the Fifth Avenue Committee, who helped negotiate the new timetable as part of the BrooklynSpeaks coalition.

Asked to comment on the recent lottery analysis, de la Uz said, “It was clear from the beginning to me that the depth of affordability at Atlantic Yards was insufficient to meet the needs of the lower income families.” However, she said advocates lacked the data to make affordability levels part of a potential lawsuit.

“A lot has changed since the project was first announced,” de la Uz added, “and under ideal circumstances, the project would build more deeply affordable units – i.e. under 40 percent of AMI – to better meet current housing need. Certainly, the market in the area can support deeper affordability and could do so even with a high percentage of the affordable units being permanently affordable.” (The apartments would be affordable for at least 30 to 35 years.)

“This is a testament to what’s possible, in terms of real affordability,” said Jonathan Westin, Director of NY Communities for Change, in that 2014 press release. While Westin has since criticized de Blasio for failing to produce “truly affordable housing,” he and NYCC did not respond to queries. Nor did the developer.

Looking at the numbers

All told, if the two middle-income “bands” in the 535 Carlton lottery were combined—given overlap in income ranges, some applicants were eligible for each band—fewer than 5,200 households competed for 192 of 297 apartments.

Murphy chart/Oder analysis/HDC data

The odds of winning ranged from one in 15 for Band 5 to one in 1,245 in Band 3.

The lottery doesn’t become fully random for each income band until selection is more than half complete. Overall, 5 percent of units are set aside for mobility-disabled applicants, and 2 percent for vision- or hearing-disabled applicants. The percentage of applicants within the overall pool roughly matched the unit percentage.

Meanwhile, 50 percent of the units overall must go to residents of the four nearest Community Districts, served by Brooklyn Community Boards 2, 3, 6, and 8. Those applications represented less than 14 percent of the total. (Typically, the community preference is offered only to residents of the Community District in which a building is sited, but Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park spans three such districts—and a fourth was later added.)

Another 5 percent preference goes to municipal employees, who were among more than 14,000 applications.

Those New Yorkers who are most rent-burdened, with incomes below $20,000 a year, were ineligible for such housing unless they had a voucher or other subsidy. (Some 3,000 of 16,000 applicants to 535 Carlton whose incomes were otherwise too low had a subsidy.)

All three existing Pacific Park buildings with affordable housing—461 Dean, 535 Carlton, 38 Sixth—are subject to the city’s recently announced homeless policy requirements for developments receiving 421-a benefits, essentially 5 percent of the building. Because the marketing plans for each building were already in process, the lottery advertisements did not exclude unit count for the homeless, according to HDC.

So 15 of the 90 low-income apartments at 535 Carlton were designated for homeless households who otherwise met application criteria and whose last known address was in the relevant Community Boards.

If a lottery applicant’s number is picked, she must provide documents like tax returns and other paperwork revealing income and rent, plus information, if necessary, about credit or landlord problems. A background check that reveals a criminal history can disqualify applicants, as can having assets valued over a set limit.

For those who beat the long odds, especially those in lower-income units, the reaction has been appreciation for a spanking new apartment in a doorman building near transit. But one 535 Carlton aspirant, commenting on a message board, called it “unfair” that middle-income households “have 3-4 times a greater chance of getting apartments” than moderate-income ones, based on units available. Actually, as the lottery analysis shows, the chances of winning an apartment were far higher.

With research assistance by Christian Vasquez and additional reporting by Jarrett Murphy.

18 thoughts on “The Real Math of An Affordable Housing Lottery: Huge Disconnect Between Need and Allotment”

I hope you will all notice that the latest lottery for housing in NYC they have left out an entire group of single people who want one bedroom. They have not included single people who make between $ 38,101 through $49,337. Then they state that they have affordable housing for those who are single and make between $ 49,338 up to $ 104,775. I am sorry but if you make that kind of money you do not need or should have affordable housing. Can we remember those who make more than $38,101 and $ 49,337 do we not count in the City of New York?

So much this. This is the problem with all of these lotteries. It’s 2020 as I write this, and it’s just getting worse.

How do we work to get these guidelines changed going forward? I feel like I want to *do* something.

I agree with Bronx4310, I was in that situation for a long period of time and was one who “made too much money” for a single individual. I also want to address something Bronx4310 may have alluded to. Singles who do qualify are often steered to studio apartments and not one bedrooms. The main issue of affordability is hardly ever addressed by any article…..the affordability formula! Technically I’m paying 30% of my gross income for rent. But look at what happens when one has to put aside more money for retirement savings, or has to pay a debt (consumer credit, income tax, rent increase, etc..) you’re not paying 30% you’re paying 50% of your take home income for rent. Not to pile on but many workers have to forego working overtime knowing this has an effect on making their rent increase at re-certification, the next year. Every contract year (approximately every 4 to 5 years) we get a raise which also spikes up the rent for that year and then of course goes down again the next year when retro-active pay is not included. Even without overtime, consumer credit debt, benefit deductions, I’m paying 50% of my income for rent. This is why affordable housing is not affordable for people who work for the city and the state. It’s an open secret that many city and state workers either make too much money as singles or like me have to use a whole paycheck to pay rent. The affordability formula has to be re-worked.

Exactly, affordable housing is 30% of your take home pay, not your gross income. 30% of your gross works out to almost 50% of your take home. Do you actually believe the 1% and politians don’t know this? The system is rigged against us. Affordable housing in New York is not designed for the middle class, hence putting most of the “affordable” apartments in this tier where you pay 50% of your net pay. Tax breaks for these properties benefit the construction companies, keep the middle class struggling.

Director of NY Communities for Change is a shrill of an organization where their landlord is Forest Ratner. What the seem to forget is many of these building are not affordable due to the lack of oversight by HPD, the Buildings Dept when it comes to all the construction defects many of these new buildings have. Look at the Tolan, look at Shaeffer Landing, look at ps90, Madison Park, the Sutton, the Langston coops/condos and you will find scaffolding around these fairly new buildings.

The bands I see are for 50% below AMI, and 130% above the AMI. I rarely see any affordable units go into the band between those two numbers. Furthermore, as a single parent, I need a two bedroom apartment, not a one bedroom. It does not distinguish between two people (two people in a romantic partnership) and others. I guess, I’m supposed to sleep in the living room while my kid has a bedroom? Even if I were ok with a one bedroom, on the rare times I qualify the expected rent is usually more than 50% of my income. I don’t understand why that is considered “affordable.”

Hi, Having a hard time wrapping my brain around the various income bands or tiers? Is there a key for this? Is Band 3 upper or middle income?

Hi Marc, Band 3 for 535 Carlton is low to moderate income. For a household of four, for example, that ranges up to around $92,000 annual income for the NYC region.

Ben,

Great research and data parsing. Thank you.

So is the band mentioned in the article as eligible for 1-bedrooms at $2170 then Band 4?

Hi All,

Can someone clarify the authors last paragraph please?

“But one 535 Carlton aspirant, commenting on a message board, called it “unfair” that middle-income households “have 3-4 times a greater chance of getting apartments” than moderate-income ones, based on units available. Actually, as the lottery analysis shows, the chances of winning an apartment were far higher”

Is he saying that moderate incomes/band 3, actually have more of a chance of winning an apartment?

How does that work when there are only 6/7 units typically designated to people who earn between $40K and $60K?

Would really appreciate the clarity. – Thanks

I guess I am focusing on Individual households here… So for a single who makes between 40 and 60K

Sarah, to clarify, the 535 Carlton aspirant was complaining that there were more units available for middle-income households, who earn more money than moderate income ones.

That suggested that, if the same number of middle-income households applied as moderate-income households applied, the middle-income households would have a better chance.

However, far fewer middle-income households responded to the lottery.

So, not only were there more units available for them, the chances of winning among those respondents was far greater than for moderate-income households entering the lottery.

Hope that makes sense.

Norman Oder (article author)

I was called for the American Copper Building, I literally cried for hours of happiness. Until I see they have me down under a different salary. I got a slight raise now I can’t qualify. I really don’t understand how they want people to make 43 or 45K for 2 bedrooms and pay over 1000. A lot of people making 43 or 45K will be burdened paying around 1100-1300. I make 49 and squeeze to pay 1100. But I would pay it if I got into one of these buildings. The requirements have to be fair and go higher. I don’t even have a place to live and therefore should atleast have a shot at affordable housing, but Nope. I mean Homeless is up 40%….this is 1 of the reasons why.

Hello Jennifer:

I’m sorry to hear that happened, I’ve been disqualified 3 times already. It’s depressing really. May I ask about your experience during the process for the American Copper? I have a friend who just got called for an interview and he doesn’t know if he should go or not since he doesn’t know if they’ll give him a studio or one bedroom. Plus, they won’t allow him to see the apartment before he signs the lease if qualified and approved. Any info would be appreciated. Any info on credit qualification? Did they tell you what the credit bracket looks like? Thanks! Would really appreciate it!

Pingback: De Blasio Expands Affordable Housing, but Results Aren’t Always Visible – H2O Of Live

Pingback: De Blasio Expands Affordable Housing, but Results Aren’t Always Visible | MIDTOWN SOUTH COMMUNITY COUNCIL

Pingback: Mapping New York City’s affordability gap - fmm

Pingback: Odds of winning an affordable housing lottery in NYC are better than you think – 6Sqft – allee