Share This Article

“By building long‑lived gas infrastructure now, we make New York’s emission‑reduction goals harder and more expensive to reach and risk forcing abrupt, disruptive adjustments later.”

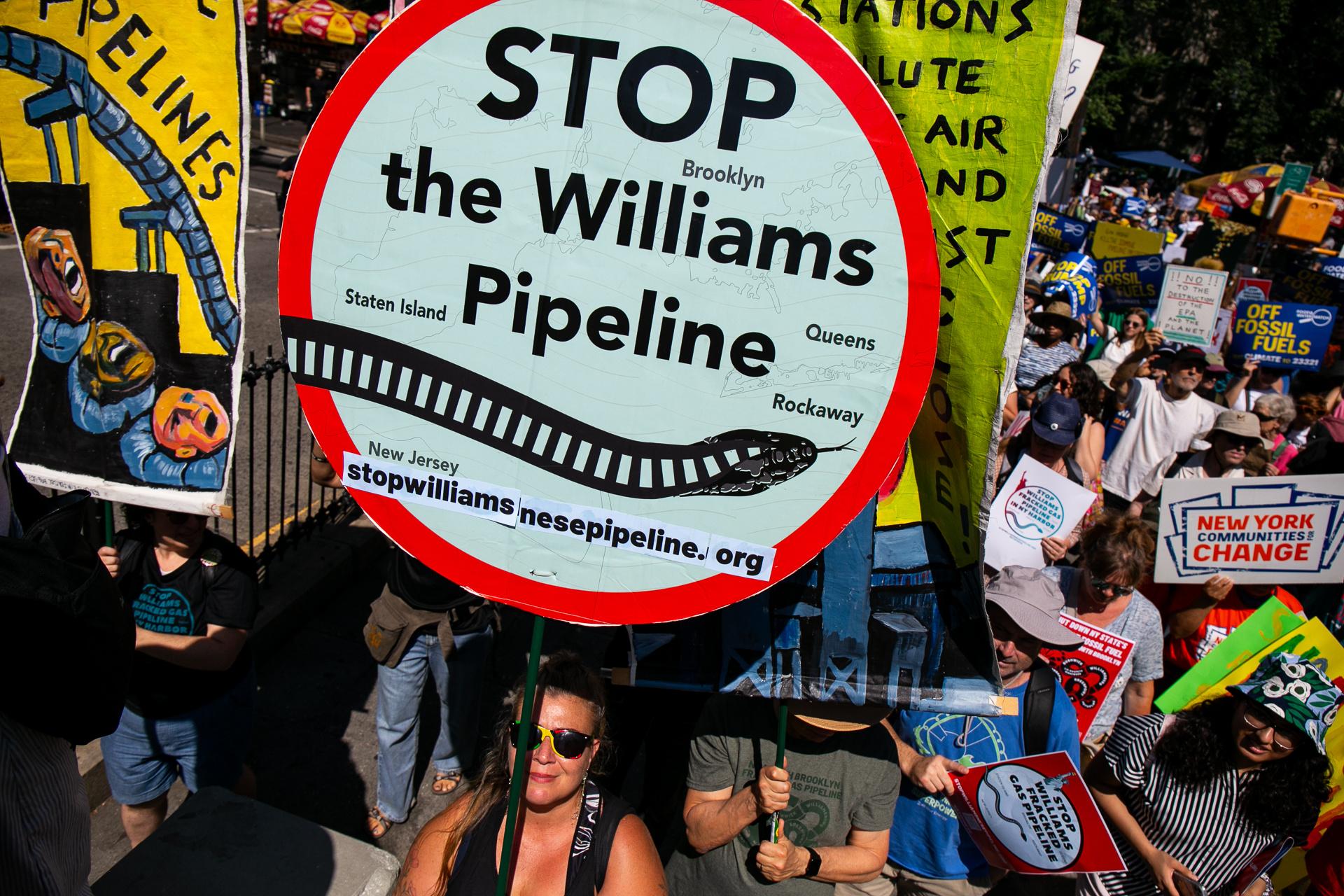

New York faces a critical crossroads: regulators have approved the Williams Northeast Supply Enhancement (NESE) pipeline, doubling down on fossil fuel infrastructure when accelerating the clean transition is most urgent. Approval does not end the debate—it intensifies it, as communities and environmental groups now turn to the courts to halt the project.

Proponents present NESE as a reliability lifeline for rising energy demand. Yet the problem is not supply shortage, but a policy choice about what kind of supply we build amid aging infrastructure. Investing in long‑lived gas systems signals to markets that climate goals can wait and wastes capital when a strong economic case already exists for accelerating renewables, storage, and efficiency to cut peak loads and bolster resilience.

There are three clear reasons New York should confront the consequences of approving NESE and other expansion projects:

First, the science is clear: new gas pipelines lock in decades of methane and carbon dioxide emissions. Methane routinely escapes during production and transport, eroding any short‑term climate advantage that gas might have over coal. By building long‑lived gas infrastructure now, we make New York’s emission‑reduction goals harder and more expensive to reach and risk forcing abrupt, disruptive adjustments later.

Additionally, the local environmental and public health impacts matter. Pipeline construction and the associated compressor stations threaten water quality, wetlands, and coastal ecosystems—concerns that Northeast states have repeatedly cited when exercising their water-quality review powers. For communities near the Rockaway Transfer Point and routes through New Jersey and Pennsylvania, the risk of spills, habitat damage, and degraded air quality are not abstract; they are lived realities that hit low-income and fenceline neighborhoods hardest.

Finally, renewables paired with battery storage are often cheaper than new fossil infrastructure especially when full system costs are counted. With investors moving away from long‑duration fossil assets, new pipelines risk becoming abandoned assets as policy and demand shift toward clean alternatives.

Ultimately, we pay the price. Utility customers would be stuck paying off this pipeline for years, even at a moment when New Yorkers are already struggling to afford their energy bills.

Approval has already triggered legal challenges. A coalition including NRDC, Earthjustice, and Surfrider Foundation has filed suit in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. They argue New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation violated the Clean Water Act by granting permits for NESE. The lawsuit underscores risks the pipeline poses to water quality and coastal ecosystems, and shows opposition will continue in the courts as well as communities across the region.

The practical alternative to NESE is not an abrupt switch—it is a phased approach that safeguards reliability while cutting emissions. New York can chart this course by deploying offshore and onshore wind, scaling rooftop and community solar, expanding battery storage, and investing in demand‑side measures like weatherization and smart grids. Communities must be protected by retiring fossil infrastructure and ensuring short‑term reliability gaps are met with clean, dispatchable resources and regional coordination.

State approval of NESE does not absolve lawmakers of responsibility. Legislators cannot claim climate leadership while allowing long‑lived fossil infrastructure to advance. Every dollar spent on pipelines is a dollar taken from renewables, storage, and efficiency. Every year of delay makes the eventual transition more abrupt and costly.

With lawsuits now challenging the approval, legislators face a critical choice: defend communities and accelerate clean energy, or side with industry and entrench fossil fuel dependence. Legislators must now decide whether they will be remembered for protecting New York’s future or for locking the state into decades of carbon emissions.

Sophia Dimont is a program coordinator for Students for Climate Action, a non-profit dedicated to engaging high schoolers in climate advocacy, civic leadership, and policy initiatives.