If Question 1 is approved, primary and special elections for city offices will feature ranked choice voting, where voters will be able to rank their top five candidates, with those preferences helping to pick a winner if no candidates gets a majority of first-place votes.

Starting Saturday, registered voters can vote to strengthen the boards that regulate police misconduct and public officials’ conflicts of interest, boost the independence of the public advocate and borough presidents, improve the city’s budget process, and elevate the power of the City Council—a little.

They can also vote to change the way city elections are run—a lot.

And they can tinker with the smallest details of the city’s land-use process—barely.

Question 2: Changes to empower the Civilian Complaint Review Board

Question 3: Changes to lobbying rules, the composition of the Conficts of Interest Board, governance of the city’s M/WBE program and the way the Corporation Counsel is selected.

Question 4: Independent budgets for some city offices, creation of a “rainy day” fund and tweaks to the city’s budget process.

Question 5: Add time to the city’s Uniform Land-Use Review Procedure.

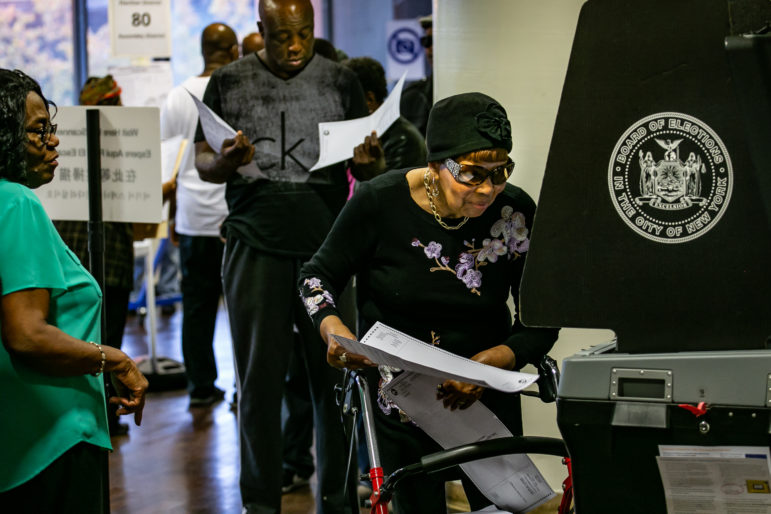

On New York City’s 2019 ballot are races for public advocate and one Council seat. Both offices are now held by people elected in a February special election. Judicial offices are up for a vote all over the city. District attorneys offices are on the ballot in three boroughs, but two of those “contests” feature an incumbent running unopposed.

In an election year that is largely a dry-run for early voting ahead of the 2020 presidential race, the five ballot questions present voters with the chance to make what as a whole represents very modest change to the way city government works. Given the sweeping mandate that Council Speaker Corey Johnson gave to this year’s Charter Revision Commission, its recommendations—particularly on land-use—look like small ball.

But as Common Cause-New York executive director Susan Lerner and Rachel Bloom, policy director at Citizens Union, told the Max & Murphy podcast (on what is hopefully a temporary hiatus from the WBAI airwaves) on Wednesday, the changes are substantive if not sweeping.

It makes sense, they said, to give the Civilian Complaint Review Board the right to investigate when officers who are the subject of a complaint lie to investigators, and to allow CCRB’s director to issue subpoenas. It’s long past time, Lerner and Bloom argued, to give the public advocate and comptroller a guaranteed share of the city budget so they can’t be undermined by a vindictive mayor or Council.

The two disagreed on whether question 3, which would change lobbying rules, alter the way the Conflict of Interest Board is composed and allow the Council to weigh in on who is appointed to be the city’s top lawyer, is too broad. But they concurred that the land-use changes reflect the commission’s failure to grapple with the most significant problems facing the city.

Amid the incrementalism that pervades the commission’s proposals, however, “ranked choice voting” (RCV) represents a significant change, the two advocates said. In all city primaries and special elections aside from citywide seats, nowadays a candidate in a crowded race can win with a small minority of votes.

Because of term limits, “Every eight years, there are extremely competitive primaries in these districts,” said Bloom. “It feels like an abundance of riches. ‘How do I pick one over the others?'” With RCV, voters can pick one but show support to others as well.

“It’s a way to help voters make sense of crowded candidate fields which, luckily, we have a lot of here in New York City because of our excellent campaign-finance system,” Lerner said. “We believe that Ranked-Choice Voting, which allows you to rank up to your five preferred candidates, but to vote for only one if that’s what you prefer to do, is really well suited for our election context here in New York City.”

Here our full conversation below. And learn more about the ballot questions here.

0 thoughts on “Charter Reform Proposals: One Big Change and Lots of Modest (But Important) Tweaks”

Ranked voting would be a profound change in NYC politics, especially in the all-important Democratic primaries, encouraging civility and consensus-seeking and ensuring that the winner of this process enjoyed actual majority support in the primary electorate, an invaluable (yet currently rare) asset in the general election and (more important) in actual governance. In Maine’s 2nd Congressional district, in the first first federal election ever conducted under a ranked-voting system, Jared Golden came in 2nd to the then-incumbent GOP candidate – yet he won, and represents that district in the House today, with fully accepted legitimacy, thanks to being the second choice of most voters for third parties in that election. This reform also eliminates the need for costly, low-turnout run-off elections – and perhaps sets the stage for future single-stage nonpartisan city elections for Council members and the mayor as well, with greater diversity (ideological, ethnic, geographical, etc.) of candidates but also greater broad-based support for the eventual elected officials once they are in office. It’s worth recalling Bill de Blasio came in first in the 2009 primary, but with just a third of the vote. Would ranked voting have resulted in a different candidate? Unclear. But whoever emerged as the victor under ranked voting would be a stronger candidate, and ultimately a stronger mayor.