Brooklyn Councilmember Crystal Hudson claimed victory after two April rezonings yielded 35 percent affordable housing. But details on non-profit partners and anti-displacement commitments were revealed only after repeated inquiries. Even now, formal documents remain under wraps.

Adi Talwar

A new 17-story residential building is planned for the rezoned lots at 870-888 Atlantic Ave. in Brooklyn. A piece of 870 Atlantic is shown here.In April, Central Brooklyn Councilmember Crystal Hudson surprised some observers when she triumphantly announced a “paradigm shift” for securing affordable housing at two proposed 17-story developments in Prospect Heights and Crown Heights, after earlier suggesting the applicants wait for a more comprehensive plan for the under-built Atlantic Avenue corridor.

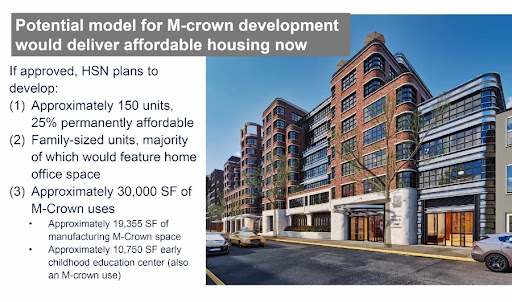

The developers would get their spot upzonings, after agreeing to making 35 percent of the 438 units affordable to low-income renters, thanks to a separate agreement outside the Council rezoning process. Developers, Hudson said, “can do more than MIH.” Indeed, the share under the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing, or MIH, rules is 30 percent affordability, and at higher average rents than Hudson secured.

But seven months after Hudson signed off on the residential towers at 870-888 Atlantic Ave. and 1034-1042 Atlantic Ave., questions over official documentation and enforcement mechanisms linger, even as Hudson and the Department of City Planning (DCP) embark on a comprehensive rezoning along the corridor, also announced in April.

Documents confirming the affordable housing commitments and the counter-parties, including $200,000 in anti-displacement funds, have not been made public, though Hudson in an interview April 26 said she expected they would surface that week.

After months of queries from this reporter, Hudson’s office on Dec. 1 finally released a summary of agreements, which revealed that the nonprofit housing groups Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC) and IMPACCT Brooklyn, which will help market the affordable housing, had signed the agreements and will also receive the funds aimed at helping low-income tenants and longtime owners remain in their homes. But that did not explain how and where the agreements have been memorialized, or the reason for the delay.

In an interview after the resolution was announced in April, Hudson said she did not know what groups would get the anti-displacement funds and that she would seek “suggestions and recommendations.” Her office did not respond to a request to clarify that statement.

A shifting pattern

When Hudson submitted testimony in January to the City Planning Commission (CPC) on the two proposed buildings, she seemed poised to pause development around the half-mile corridor where six other large projects had been approved since 2019.

DCP had been encouraging individual applicants to build big in the area after designating Atlantic Avenue, along with Fourth Avenue, an “opportunity corridor” that can accommodate significant new density in Brooklyn.

But Hudson warned that the series of “developer-initiated spot rezonings”—by then having paved the way for more than 1,600 apartments—“has resulted in a patchwork of new residential developments that do not adequately meet the needs of local communities, are out of sync with their surrounding neighborhood, and have the capacity to greatly exacerbate gentrification, particularly in [nearby] majority-Black neighborhoods.”

Hudson’s stance on the project would likely make or break the planned development thanks to the Council’s informal tradition of “member deference,” which typically gives local members veto power over projects in their districts. In March, Hudson, with 36th District Councilmember Chi Ossé and others, asked DCP for a neighborhood study, citing Brooklyn Community Board 8’s longstanding efforts to incentivize affordable housing and job-creating space on blocks shackled by outdated manufacturing zoning.

The result she announced in April reflects a larger, long-standing debate over how the city should approach its land use decisions, who should be at the table, and whether projects should be required to align with a more comprehensive neighborhood, or even citywide, plan— rather than the project-by-project approvals that, as in this case, wound up in last-minute, closed-door negotiations.

Norman Oder

Looking east from the intersection of Atlantic Avenue and Vanderbilt Avenue. In the foreground is the site for 840 Atlantic, while the low-rise buildings of 870-888 Atlantic occupy the parcel just before the CubeSmart on the left.In April, Hudson said she had gained commitments for more affordable housing than previously pledged: 35 percent (153 units), available to renters in three low-income tranches averaging 54 percent of Area Median Income, or AMI: 15 percent at 40 percent AMI, 15 percent at 60 percent of AMI, and 5 percent at 80 percent of AMI.

For a family of three, that translates to income caps of $48,040, $72,060, and $96,080, respectively, under 2022 AMI figures, with one-bedroom units renting at $1,001, $1,501, and $2,002, and two-bedroom units renting at $1,201, $1,801, and $2,402. (At the time of the announcement, before the recent jump in AMI, Hudson cited figures of $38,000 and $57,000 for two-person households.)

The deeper affordability commitments mirrored recent high-profile land-use fights over the failed One45 project in Harlem and Council-approved Innovation QNS in Astoria. Both involved developers agreeing, after being pushed, to offer more than the MIH minimums—though, in the former case, not enough for the local councilmember.

Rendering via Archimaera

A rendering of the development proposed for 870-888 Atlantic Ave. Note that applicants for 840 Atlantic, in the background, contended that the image exaggerated the height of their proposed 18-story building.

Announcing the deal on the two Atlantic Avenue projects, Hudson said the city had also agreed to the requested rezoning study of the larger neighborhood, encompassing blocks east of Vanderbilt Avenue, the eastern end of the Pacific Park (formerly Atlantic Yards) project, up to Nostrand Avenue.

When on April 28 the Atlantic Avenue rezonings finally passed, Hudson issued a press release, with supportive quotes from elected officials, Community Board 8 leaders, and Bernell Grier of IMPACCT Brooklyn. (According to a Dec. 27, 2021 letter from the 1034-1042 Atlantic developer to then Borough President Eric Adams, IMPACCT had already been contacted about administering the affordable units. It’s unclear when FAC got involved.). Absent, however, was any documentation of the commitments, or acknowledgment that IMPACCT and FAC were part of the agreement.

The summary provided Dec. 1 by Hudson’s office noted that, if government funding is not acquired to support the units that exceed MIH requirements, the developers still must provide them—a hint that the developers might first seek subsidies from the city.

In April, some community members dissented: “While the deal does include more income-targeted housing,” wrote Jack Robinson, a member of CB 8’s Land Use Committee, updating a petition he co-authored that had called for a comprehensive neighborhood plan, the “closed-door negotiations” represent practices “the councilmember herself has vowed to end.” The approvals, he added, could “set precedents for height, density and use for the entire corridor.”

Others had recognized the need for a plan. At a CPC meeting in February discussing the two Atlantic Avenue proposals, commissioner Anna Hayes Levin noted how the commission had recently reviewed private zoning applications for more than 1,500 units in the area. “That amounts to de facto planning by the private development community, without the nuance and city commitments that would accompany a neighborhood rezoning,” she said.

Making a deal

After Hudson’s critical statement in January, which noted that the projects had advanced before she took office, the real estate publication The Real Deal pronounced, “Council member spikes two projects in first week.” She was charged with NIMBYism on pro-development Twitter.

Meanwhile, Hudson told City Limits, some stakeholders who joined her letter to DCP requesting the neighborhood study told her that a deal was possible, and that gaining a commitment of 35 percent “deeply affordable housing” could “set a new standard.” While Hudson would not specify those advisors, the signatories included Grier as well as Barika Williams of the umbrella Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development (ANHD), which later noted that the city put communities in a reactive position and praised Hudson’s push for proactive planning. “True community planning is not just about process but outcomes,” ANHD said.

Hudson’s negotiation strategy followed the logic of a 2021 ANHD report, Not All Housing Units Are Created Equal, that advised the city to “approve private site rezonings on a case-by-case basis only where they would bring a higher ratio of affordable housing than exists today.”

Hudson said she faced pressure to make it a package deal—the Atlantic Avenue projects were key to getting the city to commit to a larger neighborhood rezoning study. “I don’t think that we would have had the investments in the comprehensive plan,” she told City Limits, “if these projects didn’t move forward.”

While DCP would not confirm that when contacted for this article, the Adams administration, under the rubric of “City of Yes,” has proposed multiple policies to increase supply, like reducing parking requirements and allowing developers to build more small units .

Hudson’s April announcement frustrated the Crown Heights Tenant Union (CHTU), which argued that new market-rate housing would increase displacement pressure. “A ‘community benefits agreement’ that didn’t even ask the community what we needed or wanted is exactly the kind of thing Cumbo would do,” the group tweeted, referring to Hudson’s predecessor in the district, former Councilmember Laurie Cumbo.

“I have been talking to stakeholders at every step of the way,” Hudson countered. Though obviously not all: some signatories of Hudson’s letter, like Robinson, said they weren’t consulted on the final deal, and CHTU members had not signed the letter to begin with.

Transparency was hampered by timing: the negotiations were resolved only on the morning of April 12, after Hudson first asked for 50 percent affordability. (The same land-use lawyer, as well as the same architect, represented the two unrelated developers who pursued the rezonings.)

The delays in transparency contrast somewhat with a previous agreement negotiated with CB 8, as well as, a separate “Community Benefits Agreement” regarding a project by developer Totem in Sunset Park. The details of that project were at least shared before the rezoning passed with the blessing of Councilmember Carlos Menchaca. Signatories were four non-profit organizations, three involved in workforce training and one, FAC, in affordable housing.

A long history: The M-CROWN district

Hudson, a former chief of operations to Cumbo and first deputy public advocate of community engagement at the Public Advocate’s office, represents a gentrifying district that includes Prospect Heights, Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, and parts of Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant.

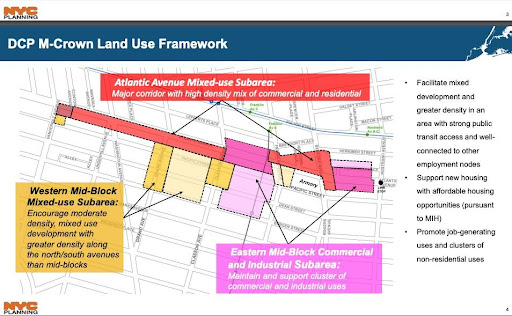

Since 2013, a subcommittee of Brooklyn Community Board 8 has studied—and, unusually, welcomed—a potential rezoning of blocks east of Vanderbilt Avenue, in a district dubbed “M-CROWN,” which stands for “Manufacturing, Commercial, Residential Opportunity for a Working Neighborhood.” But the Department of City Planning was resistant, declaring in 2016 that it could not allot the resources unless CB 8 backed the mayor’s larger affordable housing plan.

In 2018, CB 8’s chair, then-Councilmember Cumbo, and then-Borough President Eric Adams wrote to DCP endorsing the M-CROWN plan, saying it “would spur significant housing production” and commercial development.

Though DCP’s director at the time, Marisa Lago, responded supportively, she warned that new zoning tools, such as those being studied in Gowanus, were required, and cited “outstanding, challenging issues.” Translation: DCP has resisted a requirement for job-creating ground-floor uses, considering it burdensome to developers, according to Gib Veconi, who leads CB 8’s M-CROWN subcommittee.

A zone of growth

Meanwhile, private rezoning applications percolated. Today, while the blocks show only partial transformation, it’s clear how this area came into focus. After all, the district abuts the 22-acre Pacific Park site, which is the product of a state override of zoning, as well as a thriving retail and restaurant corridor on Vanderbilt Avenue.

Two towers near the Barclays Center were recently completed, and two others, along Dean Street between Carlton and Vanderbilt avenues, are nearly complete, which means eight of 15 (or 16) towers in the project will have opened. The recently completed towers have 30 percent affordable units–as will, likely, the two new ones—but only at 130 percent of AMI, for middle-income households.

Norman Oder

View of 870-888 Atlantic Ave. site, with Pacific Park towers in the background and 809 Atlantic Ave. in foreground at right.Over the MTA’s two-block Vanderbilt Yard, six more towers are planned, containing more than 3,200 apartments. They rely on a two-phase platform to protect the railyard’s storage and service functions. That platform construction was supposed to start in 2020 and then was expected to start this spring, but has not yet launched.

Spot rezonings by the city have unlocked nearby sites. At the northeast corner of Vanderbilt and Atlantic (in Community District 2), the transition zone begins with the anomalous 809 Atlantic Ave. a slender 29-story tower-on-a-base, with 264 units, that gained air rights from an adjacent historic church that the developers agreed to repair. (It’s now marketed as 545 Vanderbilt, dubbed The Axel.)

On the southeast corner, at a site largely occupied by a drive-through McDonald’s, a developer last year got a rezoning for what was billed a blocky 18-story building, 840 Atlantic. Though tenant McDonald’s has sued to block its expulsion, developer Vanderbilt Atlantic Holdings filed building permits to qualify for the 421-a tax break that expired in June.

A little farther east on Atlantic are the recently-rezoned parcels at 870-888 Atlantic, currently six attached two-story mixed-use buildings, plus a used car lot and parking lot. A CubeSmart self-storage building sits just to the east.

Two blocks east of that, past a motley group of auto-related functions and commercial buildings are the recently rezoned 1034-1042 Atlantic, currently two vacant buildings. One parcel extends south to Pacific Street, allowing the planned building to have entrances on each street. Another CubeSmart is adjacent.

Adi Talwar

A view of 1034-1042 Atlantic Ave., with 1010 Pacific Street in the background, in April 2022, shortly after Councilmember Crystal Hudson announced the rezoning agreement.One block to the south, along Pacific Street, three nine-story buildings have been approved since 2019 as spot rezonings; two are under construction, with one, 1010 Pacific Street, dubbed Pacific House and now leasing units, directly behind the 1034-1042 Atlantic site.

One block east, on the north side of Atlantic in western Bedford-Stuyvesant, the City Council last year approved 1045 Atlantic, 17-story, 426-unit building, which Community Board 3 had encouraged but unsuccessfully tried to downsize.

A learning curve for CB 8

Hudson’s negotiations also cast a light on past rezonings in the area, which delivered less than promised and were, apparently, quite profitable. The 1010 Pacific St. project, which was cut by the CPC from 11 to nine stories, lost an initially proposed historic facade and cultural space.

The affordable housing, which the project’s attorney Richard Lobel said “does indeed contemplate Option 1″ under Mandatory Inclusionary Housing—25 percent of the units averaging 60 percent of AMI—instead is being built at the permissible Option 2, or 30 percent of the units averaging 80 percent of AMI.

In the 1050 Pacific St. rezoning, Lobel—who also represents the two recently rezoned projects—claimed that his client, a long-term owner, intended to develop the building and also build only two-bedroom units. But that was not to be.

Both projects, owned by separate developers, were sold to David Bistricer’s Clipper Realty. The 1010 Pacific parcels, bought in 2015 for $8.5 million, were sold, post-rezoning, in November 2019 for $20.25 million.

Given that experience, CB 8 got developer Elie Pariente, who proposed a rezoning nearby at Pacific Street and Grand Avenue, in 2020 to sign a separate agreement to include job-creating space and to limit the building’s height to nine stories—while granting more bulk than under the board’s M-CROWN guidelines. Cumbo ensured affordability at MIH Option 1, via a zoning text amendment.

Last year, the 840 Atlantic proposal generated significant controversy, given that CB 8 saw it as a precedent for buildings significantly larger than M-CROWN guidelines, which would limit Atlantic Avenue buildings to 14 stories.

After CB 8’s advisory vote opposing the project, the Land Use Committee, at Cumbo’s behest, reversed itself to support an 18-story building that would step down to 14 stories and deliver MIH Option 3, the deep affordability option, with 20 percent of the units at 40 percent of AMI. (It also would include low-cost arts space, to be occupied by a Cumbo ally.)

But the full board, either resistant to or confused by the last-minute changes, could not deliver a majority to support the revision with several members abstaining. That meant CB 8 could not sign a separate agreement with the developer, leaving the promises in jeopardy.

Given that history, it’s no surprise that Hudson found members of CB 8 divided regarding the two recent rezonings. Board leaders sought to negotiate with the developers, who agreed to the deep affordability option—20 percent low-income units—plus job-creating space, while gaining 21 percent more bulk than CB 8 guidelines.

That led some CB 8 members, along with Crown Heights Tenants Union members, to launch the petition, now signed by nearly 1,400 people, asking the Council to reject two “17-story luxury buildings” and back the neighborhood plan that would address parks, schools, and street safety. (One petitioner, urban planner Kaja Kühl, produced a useful, if now outdated, map of the approved/pending projects.)

That all came before Hudson’s renegotiation, with advisors outside the Community Board, which gained more affordability.

Delivering more affordability while still making a profit

If the results suggest that developers can deliver more affordability and still make a profit, one question is how much to ask. The owner of 1034-1042 Atlantic, Pariente, kept his land purchase under wraps until Hudson unveiled the compromise, apparently seeking to avoid scrutiny of his cost basis.

While Pariente said at a Council hearing March 8 that he had owned the properties “the equivalent of two years,” no documents confirming that had surfaced in the city’s ACRIS database.

Late on April 12, the day Hudson announced the deal, Pariente’s $14 million purchase price appeared in ACRIS, indicating a contract date in December 2019 but a sale date on March 9, one day after the Council hearing.

A ballpark estimate, using the per-square-foot values from the 1010 Pacific sale, suggests the rezoning might be worth at least double the purchase price, at least before an adjustment for the deeper affordable housing and other costs.

Developer Yoel Teitelbaum, who has no track record in the neighborhood, had not even bought 870-888 Atlantic, he told Hudson at a Council hearing in March, and no transaction has since appeared in ACRIS. So the agreements negotiated in April are aimed to ensure that, whoever develops the properties, the promised affordability will be maintained and the anti-displacement funds allotted.

Neither the developers nor the nonprofits involved responded to queries from City Limits.

A stop to spot rezonings?

The separate area rezoning announced in April is finally on its way, Hudson aide Andrew Wright told Community Board 8’s Land Use Committee on Oct. 6. One cause of the delay was finding a facilitator for public workshops. The steering committee for the Atlantic Avenue Mixed Use Plan (AAMUP) first met Dec. 1. Working groups will analyze issues like transportation, open space, housing, and land use, with potential capital improvements. Meetings should last through spring.

Meanwhile, in what could portend tension between the community board and councilmember, CB 8’s Land Use Committee has begun hearing presentations for another spot rezoning, encouraged by the previous administration, for 962 Pacific Street, the last parcel on the block still zoned for manufacturing, and at a scale commensurate with the previous spot rezonings.

Landowner Nadine Oelsner said the project would include 25 percent affordable housing units (of 150, under MIH Option 1) and more job-creating space than in similar projects, in a shovel-ready site, and that she had paid to relocate the previous commercial tenant. She has already partnered with the Fifth Avenue Committee regarding affordable housing.

Though Hudson in the spring told CB 8 that she was putting a moratorium on spot rezonings, some key CB 8 board members, including Veconi and former Land Use Chair Ethel Tyus, applauded the 962 Pacific plan, also presented with attorney Lobel, for responding to CB 8’s goals.

Hudson’s aide Wright, however, reiterated the councilmember’s position, citing the limited resources available to DCP. “We need to make sure that all of those resources are fully focused on this rezoning process,” Wright said, adding that the goal is to deliver “a well thought-out” plan from the community.”

Oelsner, who noted she had attended CB 8 meetings to understand their requests, said her family’s loan would come due soon. “If I can’t get some movement on here, I’m going to lose this property,” she said. “And the next person sitting here, they’re not going to care anything about this community board.” She did not respond to a query about the loan’s deadline for this story.

During the discussion in October, committee member Peter Krashes asked Lobel, the land use attorney, about the agreements regarding the two Atlantic Avenue projects rezoned in April. Lobel said it would be a conflict to “comment on applications brought by other clients at this time,” but said, “should you wish to talk to members of the Community Board about it, that’s your right.”

CB 8, though, was not a party to either agreement. “We have not requested the CBA documentation for either project, and it hasn’t been provided to us,” Veconi stated, on behalf of the board, in response to City Limits’ recent query. He cited the value of a benefits agreement negotiated with the board.

At the Nov. 3 meeting of CB 8’s Land Use Committee, Lobel, aiming to reassure the group, said the 962 Pacific applicant would be willing to sign a Community Benefits Agreement, involving the Fifth Avenue Committee and the industrial advocate Evergreen.

That, in turn, prompted Kühl, the urban planner, to observe that previous CBAs have “gone wrong so many times” and even hidden from public view. (Also see City Limits coverage.) She asked if representatives of the Fifth Avenue Committee, if available, could add more details.

“If the last two [CBAs] could be made transparent and publicly available, that would be super-helpful,” she said. “But given that they were the counter-signatures to the last benefits agreement, I don’t see how them now being part of the development team is increasing trust and transparency.”

Another question is when the two recently rezoned properties will be constructed. The developer of 1034-1042 Atlantic took steps to qualify for the previous 421-a tax abatement, Affordable New York, which expired June 15 and requires the building to be finished by June 15, 2026. There’s no evidence that the developer of 870-888 Atlantic has done so, but Gov. Kathy Hochul, in the next legislative session, is expected to propose a replacement for the now-expired tax break.

Either way, the anti-displacement funds are contingent on construction. FAC would receive $50,000 from the developers of 870-888 Atlantic within a year after the new building gets its first Temporary Certificate of Occupancy, and the additional $50,000 within two years from that trigger date. Terms are similar for IMPACCT Brooklyn and 1034-1042 Atlantic. The nonprofits must develop and share their plans with Community Board 8 and the 35th District councilmember.

2 thoughts on “Seven Months After Contested Atlantic Ave. Upzonings, Details Finally Emerge”

They need to also add senior citizen housing in that area, and or add units for seniors in those towers

What happened to parks? Hadn’t they been promised? That’s a lot of density without planned open spaces – a partial solution that doesn’t consider how the day to day of the corridor will feel, and how, ultimately, it will become a neighborhood. Without open spaces, meeting spaces, community cannot be form d. We don’t need more bunkers.