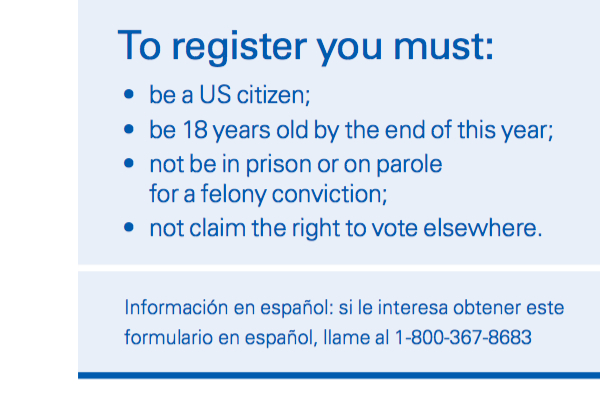

All a person released from prison and parole needs to do to restore their right to vote in New York State is complete and sign a voter registration form.

Tomorrow, when New York State sorts through the vote counts from today’s primary, there will likely be consternation over low voter turnout—the small number of people eligible to vote who actually cast ballots—as a symptom of civic disengagement.

But that turnout calculation omits one category of New Yorker altogether: people who could vote if they weren’t in prison or on parole. Civil rights advocates believe that section of the state’s population merits new attention once the elections are over and legislators return to Albany.

All but two states (Maine and Vermont) disqualify people who go to prison from voting. The other 48 employ a range of approaches.

Thirteen bar people from voting only when they’re in prison. New York and three other states—California, Colorado and Connecticut—prevent prisoners and parolees from voting.

The rest of the country is tougher: Nineteen states block prisoners, parolees and people on probation—a form of supervision that takes the place of prison, different from parole, which occurs after prison. And 12 states keep people off the rolls even after they’ve completed their sentence—whether its prison, parole or probation—some forever, and some for a specified period.

There are roughly 54,000 people in New York State prisons and another 36,000 or so on parole. New York’s disenfranchisement system can be seen in operation by looking over the recent lists of convicted people that the Office of Court Administration sends on a monthly basis to the state Board of Elections, which CityLimits.org obtained via the Freedom of Information Act.

The list for August contains 3,462 names. At least 1,092 of the people on the list were from the five boroughs—roughly in line with the city’s share of registered voters statewide. Nearly a quarter of the people listed had been convicted of drug crimes (see chart below)

Voting rights advocates worry less about the process of getting kicked off the voter rolls, and more about the challenges people face when they try to restore their franchise after completing their sentence.

Some people finishing their time don’t know their rights, advocates say. More problematic, some local election officials don’t know their rights either, with some believing (erroneously) that former prisoners or parolees need some documentation of their freedom to vote (they don’t) and others being confused about whether probationers also face a bar to voting.

“We found that because the policy is so complicated, many election officials were confused,” says the Brennan Center’s Vishal Agraharkar of a survey done in 2003. “They were telling people on probation that they couldn’t vote.”

Later that year, the state Board of Elections sent out a memo clarifying the state’s law for local election officials, and in 2006, the board conducted training on the issue. State law was changed in 2010 to require prison officials and parole officers to inform people of their rights and provide them with voter registration forms upon their release from incarceration or supervision.

But there’s evidence that misinformation is still prevalent. An informal survey, at our request, of 27 former inmates conducted one day this summer by an attorney for the Bronx Defenders found that 17 believed that people with felony convictions can’t vote, one heard that people with violent felonies can’t vote, and eight thought (correctly) that people with felonies can vote once they’re off parole. One person abstained.

“There has been some progress, but a lot of the confusion persists. It’s really a function of the policy being complicated,” says Agraharkar. “What we’ve been advocating is that we simplify things.”

What advocates would like to see is New York join states like Oregon, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire and Massachusetts and allow people to vote as soon as they’re out of prison, whether they have a stint on parole or not.

Erika Wood, a leading expert on disenfranchisement, called for this change back in 2009, arguing that, “the shameful roots of our current law and its continuing discriminatory impact on communities of color, as well as the widespread and persistent confusion it creates among elections and criminal justice officials and the public, will not be eliminated until the law is changed to restore voting rights to people who are on parole.”

“This would create a simple bright-line rule: if you are out of prison, you can vote,” she added.

State Senate bill 3342, authored by Bronx-Westchester Sen. Ruth Hassell-Thompson, would do just that. “Parole is meant to help prevent recidivism and to rehabilitate and reinitiate a felon back into society,” the preface to the legislation reads. “Preventing releasees from voting, and from exercising a constitutional right and a civic responsibility, is a barrier to full reintegration into society. It also continues to punish people who have already served the incarcerative parts of their sentences, and that part of their debt to society.”

The bill never made it out of committee, but backers are hopeful things will be different in 2015.

(Restoring voting rights to people who’ve left prison and parole doesn’t have universal appeal. During the 2012 campaign, Republican presidential contender Mitt Romney said: “I don’t think people who have committed violent crimes should be allowed to vote again.”)

Not that the change proposed in New York will necessarily boost electoral participation. In the informal survey of ex-offenders, staff attorney Kate Rubin says, Bronx Defenders heard that, “Many of them didn’t plan to vote anyways because they think it doesn’t make a difference.” But at least they’d have a choice like the rest of us.

reported to the State Board of Elections on August 1, 2014