Adi Talwar

Homeless shelter for men located on the corner of 86th Street and 101st Avenue in Ozone Park Queens. The city faced stiff opposition from residents of Ozone Park when it first announced it’s plans for placing a facility for men at this location.

Over 500 residents of the Ozone Park community packed the halls of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in July of 2018 for a town hall meeting. Rarely do town hall meetings draw huge crowds, but this one did. It was called to confront Department of Homeless Services (DHS) officials about a proposed 113-bed men’s shelter on the corner of 101 Avenue and 86 street.

Mayor de Blasio’s plan to open 90 new shelters has been met with fierce opposition in some neighborhoods across the city. Residents cite various reasons for their objection to shelters in their backyard: an anticipated rise in crime, a projected impact on quality of life, a feared fall in property value or sometimes an alleged lack of services for the shelter population.

Perhaps nowhere in the city was the opposition to a proposed shelter more intense than in Ozone Park. Residents showed up in their hundreds to town hall meetings. They held demonstrations and filed a lawsuit. Sam Esposito, a community leader, went on a two-week hunger strike that ended with a trip to the hospital. “There was no other way I could do it. Nobody was listening to us,” says Esposito now. “I felt like I brought light to the situation,” he adds. After the city dropped plans to house mentally ill men as originally intended, the shelter opened its doors early this year.

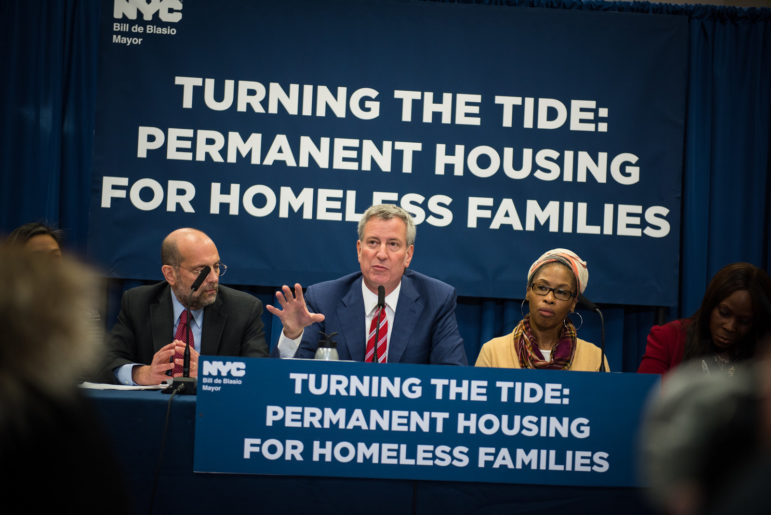

In 2017, Mayor de Blasio unveiled a multifaceted plan to combat the rise of homelessness in the city. The initiative, titled “Turning the Tide on Homelessness,” pitched a “reimagined shelter strategy” that aims to completely eliminate the city’s use of commercial hotels and privately-owned apartments known as “cluster sites” to shelter the homeless population by opening 90 new homeless shelters and expanding 30 existing ones throughout the five boroughs.

According to DHS, a move away from cluster apartments and commercial hotels will shrink its footprint by 45 percent citywide. The mayor’s plan projects a reduction in the shelter population by 2,500 in the next five years. However, it anticipates an increase in the number of single adults entering shelters by the end of the plan.

As of August 2019, there are 16,313 single homeless adults in the shelter system in New York City. This accounts for approximately 28 percent of the total number of people in the system. Single adults are assigned to different shelters than families. Research shows that, compared to homeless families, homeless single adults have much higher rates of serious mental illness, addiction disorders, and other severe health problems.

Around the city, siting single men’s shelters causes the most controversy. Single men make up 20 percent of the homeless population. Since the mayor announced his Turning the Tide plan for 90 new shelters in February 2017, the city has opened 23 sites and announced 25 others. More than a dozen of those sites have faced some kind of backlash when communities were notified. Eight of them were shelters for men.

Proposed shelters that have faced some kind of backlash include:

• 267 Rogers Avenue, Brooklyn: families with children

• 1173 Bergen Street, Brooklyn: single senior men

• 5731 Broadway, The Bronx: families with children

• 12-18 East 31st Street, Manhattan: adult families

• 158 West 58th Street, Manhattan: single adults that are employed or employable

• 52-34 Van Dam Street, Queens: adult families

• 85-15 101 Avenue,Queens: single men experiencing mental health challenges

• 306 West 94th Street, Manhattan: adult families

• 127-03 20 Avenue, Queens: single men

• 44 Victory Boulevard, Staten Island: families with children

• 97 Wyckoff Avenue, Brooklyn: single men

• 226 Beach 101 Street, Queens: single men

• 2008 Westchester Avenue, The Bronx: single adult men who are employed or employable

• 286 Audubon Avenue, Manhattan: single women

• 535 4th Avenue and 555 4 Avenue, Brooklyn: families with children

A look at some of the battles over where to locate shelters reveals that the goals of the mayor’s plan—locating shelters near the people who need them but also distributing the facilities more fairly around the city, and shifting away from the flawed current system with its reliance on hotels and cluster sites while also supplying the number of beds the city needs each night—do make for a complicated conversation about what’s fair both for communities and for the people who need a place to sleep.

But it is also clear that overblown neighborhood fears create a political environment in which local leaders face risks for supporting a sensible shelter policy. In the middle, but rarely heard amid the uproar, are everyday New Yorkers caught in a crisis.

Claims of impact, but little proof

Prior to the contested Ozone Park facility arriving, Community District 9, which covers the neighborhood, had no shelters. There are 309 homeless individuals in the system across the city that hail from this district but until now it had no shelter beds. Placing this shelter at this location was in line with the mayor’s promise to “equally” distribute them across the city. The district now has 103 homeless people living there.

Esposito says he and his neighbors would have accepted a shelter for families and children. “You can put senior citizens in there, you can put women and children in there but you’re not going to put single men in there,” he says. “This is not going to work. We are going to have problems. And we’ve been having problems ever since.”

“If you talk to the neighbors that live around there, they will all tell you that they have seen problems,” Esposito says. “They are urinating, they are defecating. Now, they broke windows,” referring to a recent incident that left three cars vandalized in the neighborhood. It is unclear who the perpetrators were, but Esposito blames the shelter residents.

Yet there is little evidence to back those claims. For example, since the shelter opened its doors in late February, in addition to a drop in top-level, index felonies, there has been a 40 percent decrease in non-felony offenses—which includes the kind of offenses shelter opponents complain about—in the local precinct compared with the same period last year. From February 28 until the end of August this year, the 102nd precinct (which is in charge of this part of Ozone Park) recorded a total of 1,197 non-felony offenses compared with 1,999 last year. The precinct also saw a decrease in public order offenses such as harassment, from 98 over the March through June period last year to 63 over the same period this year .

In the early months when the community is expected to be particularly wary of the new shelter residents, one would expect an increase in the number of complaints to 311. But the data shows a drop. Since the facility opened six months ago, there were 26 calls made to 311 for incidents within a block of the shelter, down from the same period last year, 32. So far there has been only one complaint of a “drug activity” in front of the facility. The other three complaints involving the shelter were for blocked driveways.

Asked about these findings, Esposito says residents avoid calling 311 because of mistrust in that system. He says police officers rarely show up in time to make arrests or stop the offenses. While he admits that there haven’t been any major issues, he insists there have been incidents of public urination and loitering.

The gap between perception and reality isn’t confined to Ozone Park. “When you think about nimbyism, the thing about it is that people are generally risk averse,” says Michael Hankinson, assistant professor of political science at Baruch College who has studied the subject, referring to a label—Not In My Back Yard, or NIMBY— that some shelter opponents resist. “Even if the study shows that 99 times out of a 100 you’re not even going to notice that this is here … people will fixate on that one out of a hundred times,” he adds.

Shelter skepticism is smart politics

William Alatriste for the NYC Council

Christine Quinn seen during her time as Council Speaker. Then she opposed a shelter in her district. Now, she says. ‘I didn’t know everything I know now about the difficulty of the struggle and how challenging finding affordable housing is for homeless families.’

While single men’s shelters receive the bulk of backlash, other shelters—even those that house women and children as in Riverdale where the city was accused of “bait and switch” after it converted a market-rate apartment building into a shelter for families with children —also sometimes face protest from communities. Families and children make up the majority of the homeless population in New York City. Currently 70 percent of the homeless population are families and children.

“What I find in our successful effort to open shelters across the city is that people are usually driven by fear of what they don’t know and potential change in their neighborhood,” says former City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, who now heads WIN, a nonprofit that provides shelters for homeless women and children.

At a recent town hall meeting at the Grand Prospect Hall in Park Slope, a man heckled Quinn for coming out against a shelter in her Chelsea district in 2011, during her time as a city councilmember, a position she says she now regrets. Quinn said she came out against the 12-floor, 328-bed facility at 127 West 25th St because of its large size. “If I knew everything I know now, I might be taking a different step by asking to take the number down,” she said in a phone conversation with City Limits. “But I didn’t know everything I know now about the difficulty of the struggle and how challenging finding affordable housing is for homeless families,” she adds.

Quinn’s past opposition to that shelter is not an uncommon position for a local politician to take. In almost every neighborhood where there has been a backlash to a proposed shelter, local elected officials have come out in support of the protesters. Politically, supporting anti-shelter activists might be a smart move. In local elections, a few energized voters could make the difference between winning or losing an election. “The turnout rate for local election is abysmally low,” Hankinson says. “When you have a lower turnout, these people are going to be the hardcore voters.”

One politician who might have paid the price for not coming out stronger against homeless shelters is former Councilmember Elizabeth Crowley. In 2017, Crowley lost her City Council seat to Robert Holden, who positioned himself as anti-shelter in a district that was staunchly against the facilities. She represented a Queens neighborhood where in 2016 residents successfully blocked the opening of a shelter when they showed up in their hundreds to town hall meetings and protested in front of a top official’s home.

Crowley, who spent nine years representing district 30, blamed her loss mainly on what she says was the mayor’s unpopularity leading up to the 2017 election. “The top of the ticket [the mayor] being very unpopular, receiving roughly 32 percent of the general election vote in that district and as top ticket candidates often drive elections, I do believe this affected turn out and vote in that Election District that Election Day.”

However, she admits that the anti-shelter activists may have given Councilman Holden— who ran as a Republican after losing the Democratic primary to Crowley— an edge. “I think it may have given momentum to my opponent, but I stand by the main reason being the top ticket”

A few days ago, the city announced it would site two shelters in this neighborhood. It’s unclear how activists will react to the new announcement. But Holden expressed his frustration in a statement: “I am disgusted with the way City Hall does business when it comes to housing the homeless,” he said. Holden said he presented a plan to build a school on the property where one of the shelters would be sited. He said city agencies agreed to the plan and was told the mayor’s approval was all that was needed. “I tried to fight against this shelter the right way, by negotiating with city agencies and coming up with reasonable proposals, only to have the rug pulled out from under me,” he says in the statement. “I’m sick of playing this game with City Hall, so now I will fight back the best way I know how, with my neighbors by my side.”

With its pledge to site shelters in communities across the city, it is unlikely that this time around the city will budge, especially because community district 5 has 242 people in the shelter system across the city but has no shelters located in the district. Since the city started implementing its Turning the Tide plan, it has rarely backed down from a proposed location. When it has— like it did in the Norwood community in The Bronx— it was to move to an alternate site in the community.

William Alatriste for the NYC Council

Elizabeth Crowley lost her Queens Council seat in 2017 after a fierce controversy over a proposed shelter in the district.

What’s a fair share?

Currently, the community districts with the highest share of shelters are in Brooklyn and The Bronx. For example, community district 4 in The Bronx (which consists of neighborhoods like Concourse Village, Mount Eden and Highbridge) is host to 3,733 homeless people, the highest in any community district in the city. It is also the district where the largest number of homeless individuals come from (2,297).

Overall, 35 percent of homeless individuals in the shelter system are from The Bronx, particularly the South Bronx, followed by Brooklyn, which accounts for 26 percent of homeless people in the system. The boroughs together currently host 59 percent of the city’s shelter population.

The mayor’s plan is to keep homeless people as close as possible to their communities while also distributing shelters equally across the five boroughs. “Every community board in New York City has people in our shelter system who come from it,” the mayor said in his 2017 speech about the plan. “We need a shelter system that reflects where people come from and allows people to be sheltered in their own communities,” he said.

That means communities not considered for shelters in earlier years are now slated to get them. Currently there are nine community districts with no shelters:

• Bronx 11 (Allerton, Bronxdale, Indian Village, Morris Park, Pelham Gardens, Pelham Parkway, Van Nest)

• Brooklyn 10 (Bay Ridge, Dyker Heights, Fort Hamilton)

• Brooklyn 11 (Bath Beach, Bensonhurst, Gravesend, Mapleton)

• Manhattan 2 (Greenwich Village, Hudson Square, Little Italy, NoHo, SoHo, South Village, West Village)

• Queens 5 (Glendale, Maspeth, Middle Village, Ridgewood)

• Queens 6 (Forest Hills, Forest Hills Gardens, Rego Park)

• Queens 11 (Auburndale, Bayside, Douglaston, Hollis Hills, Little Neck, Oakland Gardens)

• Staten Island 2 (Arrochar, Bloomfield, Bulls Head, Chelsea, Concord, Dongan Hills, Egbertville, Emerson Hill, Grant City, Grasmere, Heartland Village, Lighthouse Hill, Manor Heights, Midland Beach, New Dorp, New Dorp Beach, New Springville, Old Town, South Beach, Todt Hill, Travis, Willowbrook)

• Staten Island 3 (Annadale, Arden Heights, Bay Terrace, Butler Manor, Charleston, Eltingville, Fresh Kills, Great Kills, Greenridge, Huguenot, Oakwood, Oakwood Beach, Oakwood Heights, Pleasant Plains, Prince’s Bay, Richmond Town, Richmond Valley, Rossville, Sandy Ground, Tottenville, Woodrow)

The city is not legally obligated to alert communities about new shelters opening in their neighborhoods. Under previous administrations, little notice was given to constituents. Residents would only find out about a shelter after it has opened.

But the “Turning the Tide” plan calls for giving communities at least 30 days’ notice with at least one community meeting. This 30-day notice has allowed advocates to organize and form civic groups. The meetings have also provided an opportunity for activists to voice their anger at officials or other representatives. In his speech unveiling the plan, the mayor said communities deserve to know they are getting a shelter but “that does not mean if there is protest we would change our mind.” So far, this has been largely true; rarely has the city backed down due to a backlash.

When pressure on the city doesn’t work, the local activists’ next strategy is to file lawsuits. The lawsuits, which often seek injunctions preventing the city from completing or opening the shelters, typically allege that the city failed to conduct a proper Fair Share analysis, a multi-faceted assessment and community notification process city agencies must complete detailing how their new facility might impact the nearby community and how it conforms with larger goals about equitably distributing city facilities.

While these lawsuits appear not to have been successful in changing the city’s plans, they have brought to light how many community groups believe the mayor’s implementation of Turning the Tide has not been fair to communities that already have a high concentration of shelters.

Scrutiny of city’s analysis

Last year, when the city announced a 150-bed shelter for men in the old Park Savoy hotel in midtown Manhattan, residents quickly formed a civic group called The West 58 Street Coalition. In a bid to block the opening of the shelter, the group sued the city, ostensibly for safety violations like fire traps. The lawsuit also accused the city of failing to “perform proper environmental and fair share analysis.”

An environmental review study commissioned by the DHS concluded that “the presence of the facility would not adversely impact the neighborhood’s character, nor would it result in any significant moderate effects on the technical areas that comprise neighborhood character.” But activists say the study does not address the “impact on crime and other quality of life issues that siting 150 homeless men would have.”

Mainly, though, activists suspect a hidden motive behind this shelter: that by choosing this wealthy neighborhood, the mayor is trying to make a political point.

Residents also complained that Community District 5 is oversaturated with similar facilities such as commercial hotels. The district currently has 10 traditional shelters and eight commercial hotels. Only 127 homeless people are from this district but over 2,500 from across the city currently live in shelters here, according to a DHS data provided to City Limits. It’s unclear if any of the 127 people live in shelters located in this district.

However, this new site will be the first traditional shelter within a mile, DHS says. The city said it would stop the use of all commercial hotels currently serving about 1,000 people in Community District 5 by the end of the mayor’s plan.

In the lawsuit, residents expressed concern about what they say was the lack of an adequate security plan. The city, in a letter to Councilman Keith Powers, said that Westhab, the agency that would run the shelter, will provide 24-hour security with six staffers per shift. In addition, 109 cameras have been installed throughout the building and across the shelter grounds, according to documents. Multiple attempts to reach the West 58 Street Coalition went unanswered.

Strain on services seen

A year ago, when the city proposed a 300-person shelter in Blissville—a small community nestled between a cemetery, the Long Island Expressway and Newtown Creek and with a population of about 450— residents, joined by elected officials, held back-to-back protests against the proposed facility. It was to be the third shelter within a few blocks.

While residents expressed fears of a rise in crime and other quality-of-life impacts, most say they worry the homeless population will outnumber residents in an area that lacks critical services such as laundromats, grocery stores, urgent care facilities or hospitals. The nearest subway station is about a mile away.

“As someone who comes from a family that was once homeless, I have been supportive of permanent shelters opening in my district,” Councilmember Jimmy Van Bramer who came out against the shelter, told City Limits in an email. “The issue in Blissville was the lack of a strategy. Three shelters were sited in a short amount of time mere blocks from one another in the most isolated part of my district.”

William Alatriste for the NYC Council

Councilmember Jimmy Van Bramer says his concerns about a shelter in his district were about the opening of several shelters in a short period of time.

One sunny afternoon this past week in Blissville, Daryl—that’s his middle name—came to collect his mail at the shelter. Not long ago, Daryl, 64, his wife and their son lived here too, but they were moved to a hotel because of a water breakage in their apartment.

“You could be in the shelter system anytime,” he says. “You can have a fire break down in your house, or water main break. It don’t have to be your fault,” he adds. People end up in homeless shelters for myriad reasons, he says. His wife was a social worker and he is a barber and they have been in the shelter system for over four years, he said. For Daryl, it was his wife’s unexpected one-year stay at the hospital. What was supposed to be a one-day procedure in the operating room ended up being a year stay when she suffered a heart attack during the operation. “We couldn’t afford to pay the rent because she was in the hospital. That’s how we got evicted at our apartment,” he said.

Except for some shelter residents gathered under the green ash tree about 40 yards from the facility, there was scant foot traffic here one sunny afternoon. While just a snapshot in time, the scene seemed a far cry from some of the community’s worst fears.

An employee at the Van Dam Express, a deli adjacent to the shelter building, said they haven’t had problems with the residents so far. “Everybody over there is great,” the employee, who declined to give his name, said. “I’ve never called the cops,” he added.

Jimmy, another shelter resident who asked for his real name not be used says: “Not everyone is a drug addict, or a bad person or did bad things. Some people just caught a bad break.” Asked about the backlash the shelter received, he said, “If they really got to know most of us, they’ll know we are nice people just trying to better our lives.” Jimmy, 52, a former construction worker, said he’s been looking for a job but his criminal record has been an obstacle.

For its part, DHS said it will phase out the other two shelters, which are classified as cluster sites, by 2021 in line with the mayor’s plan. Community district 2 is home to over 1,000 homeless people from across the city but only about 378 homeless people come from here.

It’s not like shelters do not carry some risk of trouble. But the threat seems primarily to be to the people inside. A Daily News report last year revealed that the city was not forthcoming about crimes occurring inside its shelters. According to the paper, the city was undercounting the number of arrests and incidents inside city-run shelters. Shelters like the Bedford-Atlantic Armory in Crown Heights have been particularly problematic. The 350-bed shelter is notorious for the high number of crimes that occur inside, although neighbors complain about loitering and public urination by shelter residents.

Under Turning the Tide, the city has promised “high quality” shelters with expanded mental health services on site. The NYPD will also oversee security at all DHS shelters. For the most part, the DHS has also ended its requirement that residents leave the shelters during the day. Most of the new shelters come with cafeterias where residents can spend time and apply for jobs. This may reduce loitering, one of the main complaints of opponents.

Shelters vs. economic ambitions

There is general agreement that the lack of affordable housing is the major cause of homelessness. Where there has been a backlash against a shelter, activists say they would prefer a permanent or low-income housing instead.

In Staten Island, a borough which has about 90 percent of its homeless population scattered across the city, a plan to site two shelters there has faced stiff opposition. But the proposal to place a shelter at 44 Victory Boulevard, the heart of the Bay Street Corridor that recently underwent a rezoning, is facing the larger backlash. The Staten Island Downtown Alliance is leading the opposition to this 200-unit shelter, which will house women and children.

The opponents, who are planning to sue the city, state many reasons for their opposition to this shelter. Chief among them is that they have been working for years to make the Bay Street Corridor attractive to businesses.

“This area is poised to become an economically mixed and active neighborhood thanks to proper City Planning and the rezoning that have taken place over the last decade,” says Leticia Romauro, who is the secretary and executive director of the Staten Island Downtown Alliance and is a former chair of Community Board 1. “Placing a homeless shelter at the gateway to the north shore (Bay Street and Victory Boulevard) when we could have an economically mixed apartment building on the site does not benefit the women and children using the shelter and does not benefit the greater north shore community,” she adds. Romauro said the city should instead create permanent housing for these families. “Why keep them in a state of flux when we can provide them with a permanent place to live?”

She said businesses in the area have already lost clients because of the proposed shelter. Multiple attempts to reach those businesses were unsuccessful.

But Quinn, whose organization will be running this shelter, rejects the idea that the facility will hamper economic development.

“The idea that providing a space for struggling Staten Island families to rebuild their lives would damper economic development is not supported by any facts,” Quinn said in a follow up email. “This facility will replace an eyesore of an empty lot on Victory Boulevard with a new, state of the art five-story building that will include 10,000 square feet of new ground level retail – providing nearly 100 full and part-time jobs to the community, with priority hiring given to Staten Islanders.”

Staten Island is home to only one DHS shelter housing 46 families or 149 homeless individuals, far lower than other boroughs. Under the mayor’s plan, more shelters will be sited in the borough to house the 1200 homeless individuals who call the borough their home, according to DHS.

The shelters will always be with us

Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photography Office

Homelessness advocates and shelter opponents agree that more permanent housing is needed than the mayor’s Turning the Tide Plan envisions. But some emergency shelter system will likely be necessary even with a robust affordable-housing pipeline.

“Emergency shelter should be just that: a safe place for an adult or family to go when they are displaced for any reason,” Giselle Routhier, policy director at the Coalition for the Homeless, said in a statement to City Limits. “The growing gap between incomes and rents over the past several decades has resulted in an ever-expanding shelter system where people are staying longer and longer.”

Both advocates for the homeless and shelter opponents say they would rather see more permanent housing than shelters. But the city’s legal mandate makes it impossible to do away with emergency shelters altogether. The city’s “right to shelter” mandate is a result of a landmark decision in December 1979 by the state supreme court that forced the city and state to provide shelter for homeless men. The lead plaintiff in the lawsuit, Robert Callahan, was a homeless man suffering from chronic alcoholism who lived on the streets of Manhattan. Callahan vs. Carey triggered subsequent lawsuits that extended these rights to every homeless man, woman and child.

And practically speaking, a city as large as New York will always need to have some emergency shelter system to help people when crisis strikes. “We need compassion for New Yorkers that are feeling the worst effects of the housing crisis and robust investment in permanent housing to reduce the occurrence of homelessness,” said Routhier, whose group is advocating for 24,000 new units of housing.

While the city concedes that it needs to do more, it touts its efforts so far. “The Department of Social Services has made unprecedented investments to prevent and address homelessness, driving down evictions by over one-third by increasing access to legal services,” said Arianna Fishman, a spokesperson for the department, in a statement to City Limits. She said the city is helping more than 117,000 New Yorkers secure permanent affordable homes through its rental assistance and rehousing programs.

13 thoughts on “The Shelter Wars: City’s Need for Beds Meets Opposition in Several Neighborhoods”

Kudos to Brad Lander and others who are standing their ground and actually welcoming homeless families into our community. The 5th Avenue shelter is a block away from where he lives and two blocks from my family’s house. Like many of our neighbors, I much prefer families and children moving into the neighborhood than more Manhattan transplants who aren’t “tuned in” to the community and use this area as an affordable springboard that will eventually launch them back to Manhattan, or – if they do have families – to larger homes in prettier areas or out of town. While landlords and real estate agents profit from that type of constant turnover, the sense of place and community we have here suffers. It should be noted that most people in this community (Gowanus, Park Slope, South Slope) – while rightly shining light on financial issues – are in support of welcoming these homeless families. While they won’t come out and say it, most of those who are opposed are concerned about property value – i.e., meaning they’re not planning on staying here anyway. That’s not how we do it in Brooklyn. To them I say, “good riddance.” To the arriving families I say “welcome home.”

This is a dishonest argument. The fact is that residents stay only a brief time in homeless shelters. WIN estimates that the residents of the shelters at 535 and 555 4th Avenue will stay only about 15 months on average. They will not be integrated into the community. They are an inherently transient population–much more transient than property owners, and even more transient than renters. But most of all, public policy should not be based on certain individuals’ prejudice towards whole groups of people, including newcomers to “your” neighborhood.

With regard to using stats to prove a point that crime is down near shelters – many crimes were reported in the Elmhurst area that were directly related to shelter residents at the Pan Am hotel. The police came and refused to take reports, most likely under direct orders from the PC who reports to de Blasio. Walk into any business on QB near the hotel and talk to the managers and owners. They’ll tell you an earful.

Then the councilmember for that area is not doing their job. The CM and other local elected officials need to make a big deal about the intentional lack of NYPD response. If they don’t get in front of this nothing will happen.

Pingback: The Shelter Wars: City’s Need for Beds Meets Opposition in Several Neighborhoods – Coalición de Coaliciones

Pingback: September 13, 2019 - Weekly News Roundup - New York, Manhattan, and Roosevelt Island | Manhattan Community Board 8

Pingback: Why New York City gets gouged on homeless shelters | MIDTOWN SOUTH COMMUNITY COUNCIL

Pingback: West Side Rag » Emotional Protests Haven’t Slowed Momentum of Shelter ‘Evictions’

Pingback: New York’s War on the Homeless – The Fordham Ram

This article claims–with no supporting evidence other than to quote Christine Quinn, an interested and biased source–that community fears about homeless shelters are unwarranted. Now we have hard evidence that proximity to homeless shelters does indeed lower property values. See this New York Times article, “How Homeless Shelters Affect Property Values,” published September 25, 2019.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/25/nyregion/nyc-homeless-shelters-property-values.html

If proximity to shelters lowers property value than it is incumbent upon the City to disperse shelters as widely as possible so everyone shares the burden equitably.

Should be pointed that the IBO study has been disputed, not only by homeless advocates but also by respected researchers like the NYU Furman Institute:

https://gothamist.com/news/disputed-study-says-homeless-shelters-negatively-impact-manhattan-home-values

Pingback: In Affordable New York Brooklyn Hotels - Daniktheexplorer

A little late to the party but… Parkchester already has its share of shelters while other communities have none. Why should we be slotted for another while other communities don’t have any? Some articles cite the statistics of number of people in the shelter system who are “from” certain communities. It stands to reason, that if one is “from” a wealthy community, that they would downgrade to a middle class, then a lower class, then a poor community… tilting the numbers and making it seem like they are “from” areas that are already economically challenged, and hence, justifying concentrating homeless shelters in only some communities.