In these days of high political drama, with talk of impeachment and a declaration of emergency at the national level as local and state politicians tangle over Amazon, legal redress for victims of sexual abuse and reproductive rights, property tax reform is not the kind of topic that gets hearts a-thumping.

Well, right: Property tax reform is never the kind of topic that gets hearts a-thumping. That’s probably one reason why a system that has been acknowledged as deeply flawed for a quarter century has stayed that way.

Another reason, as a new report from the Regional Plan Association (RPA) points out, is that it’s hard to fix the property-tax system in a way that doesn’t create winners and losers—those who end up paying less, and those who end up paying more—among taxpayers. The current system suffers from several different inequities: between apartment buildings and houses, and between houses in different neighborhoods. Resetting that balance will be a daunting task.

Urgency seems to be building for some kind of reform, however. To that end, RPA has suggested four ways to address existing inequalities in the city’s property-tax system and use the system’s leverage to improve the housing market.

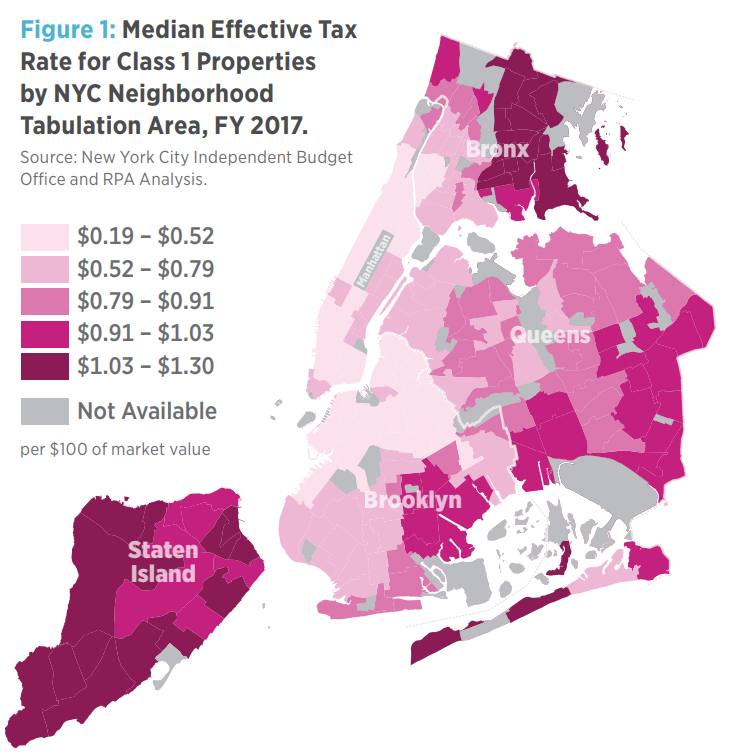

The main reason property-tax inequality is so gaping is that there are caps in place for Class 1 homeowners (three-family houses or smaller) that prevent tax bills from going up too fast. Over time, those caps mean folks in hip neighborhoods see their property values soar but their tax bills only creep up slowly, leading to a lower effective tax rate than in other areas. Getting rid of the caps is tempting but that would hurt current, low-income owners. So, RPA suggests re-assessing home values whenever they change hands and allowing only the present owner to enjoy the protection of year-to-year caps.

Class 2 rental properties are likely to see tax bills fall under any property-tax reform. But should those savings go just to landlords, or also to tenants whose rents reflect those tax bills? RPA proposes a broad, refundable renters’ credit—one that would also help the many people who rent in Class 1 properties (an amazing 23 percent of renters).

RPA treads cautiously when it comes to the long-discussed possibility of taxing vacant land to encourage development. Merely taxing purely vacant land “would not be significantly impactful from either a development or revenue generation perspective, mostly because New York is a heavily built out city with relatively little privately-owned developable vacant land,” the report found. So the city would have to think about new ways of taxing “underbuilt” land as well. But even considering such a step would demand a better accounting of just how much land is underbuilt in the city.

Finally, the Association calls for a surcharge on housing subject to “seasonal, recreational and occasional” use, meaning “pieds-à-terre, summer bungalows, and increasingly short-term rentals on platforms such as Air BnB.” The surcharge would result in some combination of additional government revenue—always handy—and apartments being put on the market to be rented as residences. If only 42 percent of the 75,000 apartments now used seasonally or for recreation were put on the market, RPA says, it would push the city’s vacancy rate above the 5 percent threshold for its housing emergency.

Read the report here.