Demetrius Freeman/Mayoral Photography Office

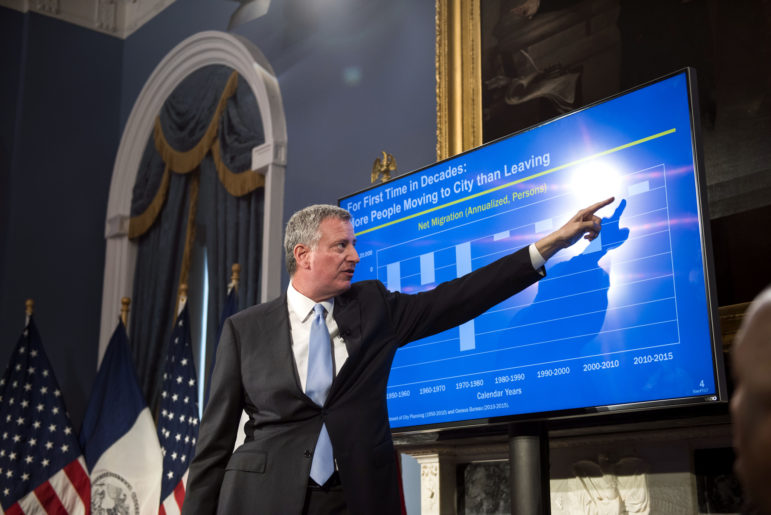

Mayor de Blasio presenting the fiscal 2017 executive budget.

Two years ago, the year-end look-ahead was bleak on the political side but brighter on the economic front. This year, it’s the reverse. The midterm elections portend more hopeful changes in Albany and Washington, while this fall’s gyrations on Wall Street reflect growing economic uncertainty with trade tensions, Brexit or whatever, and the Fed’s raising interest rates as the blunt instrument of choice to contain market excesses, whatever the consequences for workers.

While a recession doesn’t appear to be around the corner, the economy certainly seems to be shifting into a lower gear. One big question this raises is what impact a slower economy would have on New York City’s budget. For some observers the prospect of slower revenue growth means that the City must tighten its belt and reduce its workforce. Hooverism never dies, does it? I would point out that the city budget has expanded as New York City’s population and economy have grown.

Let’s keep the growth in the city budget and headcount in perspective. The strong local economy has translated into robust tax collections, rising by over 5.1 percent annually during de Blasio’s first term. That’s an increment of $2.1 billion in budget capacity each year. That revenue growth helped make possible the labor settlements, as well as increased funding for homeless, youth, and senior services, more police officers on the beat, expanded affordable housing investments, and setting aside substantial budget reserves in the event of an economic slowdown.

I’m sure if you polled pundits on whether city spending has grown faster under de Blasio than under former Mayor Bloomberg, most would say de Blasio. However, city-funded expenditures (i.e., minus spending from state and federal categorical grants) grew 3.5 percent annually after adjusting for inflation during Bloomberg’s three terms versus 3.2 percent during de Blasio’s first term.

When The New York Times reported back in June on the FY 2019 city budget agreement, it noted that the size of the municipal workforce would be about 300,000, the highest level ever. It is worth noting that at 8.7 million people, the city’s population is also at its highest level ever. And the size of the municipal workforce in relation to total payroll employment in the city over the last five years has been at its lowest share (6.6 percent) in 30 years, that is, since the city began adding back staff following the sharp post-fiscal crisis retrenchment in the late 1970s.

The city workforce is certainly larger than in 2013, but most of that increase has been among teachers and support staff at city schools and CUNY campuses, with smaller increases in police, fire, sanitation, corrections, transportation, parks, and public health. City government might have added 30,000 jobs in the past five years but the private sector has added over 500,000 payroll and independent contractor jobs in that time.

With a bigger city (more people, workers, public school students, visitors, and buildings), and more gentrification, it’s not surprising that more city government workers are needed. These investments in public services have contributed to the quality of life and the city’s vibrancy that make New York City so attractive to newcomers, and a beacon for expanding tech companies, among others.

There is also misunderstanding regarding the cost of recently-negotiated settlements with District Council 37 and the United Federation of Teachers, the two largest municipal unions. The agreements, which will set the pattern for all other city labor contracts, include wage increases over 43- and 44-month contract periods that work out to average annual increases of about two percent, essentially the same as the metropolitan-wide inflation rate the past two years. The cost of the new bargaining round will be offset in part through an agreement with the Municipal Labor Committee to generate $1.7 billion in additional health insurance savings over the 2017-2021 period. Moreover, the city had already set aside in its labor reserve funds to cover one percent annual increases (half of the new pattern) for the four years of the financial plan.

In its November modification to the budget, the mayor added the additional funds needed to cover the citywide wage increases (and associated pension contributions) through FY 2022—this means that there likely will be only slight further changes over the next three years in the personal services part of the budget that account for 55 percent of the overall budget.

Aside from the labor reserve, the city has $9.6 billion in reserves when the Retiree Health Benefit Trust is considered along with the general reserve and a capital stabilization reserve. Reserves exceed 10 percent of annual expenditure and should be sufficient to weather plausible tax revenue shortfalls in the event of economic weakening.

Significant budget challenges remain, of course. Foremost among them is the need for the State and the city to increase funding for the MTA to improve service and to more adequately fund long-term capital needs. This past June, the state pressured the city to match the State’s $418 million contribution for the MTA’s Subway Action Plan needed to address deteriorating transit service, and that pressure will continue in the coming year.

While establishing UPK was a watershed achievement in the mayor’s first term, there’s unfinished business at City Hall in achieving compensation parity for UPK teachers in community-based organizations, and in improving the availability and quality of child care for infants and toddlers. Compensation parity is essential if the mayor intends to honor his pledge to make New York the “fairest big city” in America.

The state-city Amazon-sized Amazon subsidy was a wake-up call to legislators in City Hall and Albany to quickly revisit the state-authorized as-of-right tax breaks administered by the city—the Industrial and Commercial Abatement Program and the Relocation and Employment Assistance Program—that the city is providing to Amazon at an estimated cost of $1.3 billion. It is fairly clear that the overwhelming reason the company chose to locate in Long Island City Queens was due to the city’s attractiveness to high tech professionals and the site’s proximity to the Cornell-Technion engineering campus on Roosevelt Island. It would have been much better to invest those resources in improving the city’s transit infrastructure or public housing. While they’re at it, legislators should also revisit and similarly curtail wasted commercial property tax breaks handed out in the Hudson Yards area, courtesy of the #7 financing scheme cooked up by former mayor Bloomberg.

Mayors don’t have a lot of control over the ups and downs of the economy, but they can try to influence how broadly the fruits of growth are shared, and not just through tax and budget policies. While de Blasio’s immediate predecessors, Mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg, also experienced boom years during their tenures, they did little to channel gains to the less well-heeled.

De Blasio, on the other hand, advocated raising minimum wages, including significantly increasing pay for low-wage nonprofit workers employed under city-funded human services contracts. With the City Council, he also provided more benefits and protections for vulnerable workers, including paid sick days, fair scheduling practices in retail and fast food businesses, and safeguards for independent contractors and against wage theft. The recent enactment by the Taxi and Limousine Commission of a minimum pay standard for app-dispatched drivers broke historic ground in boosting annual earnings by nearly $10,000 for 75,000 independent contractor drivers.

This expansion, and sustained state minimum wage increases, have provided historic gains for New York City’s low- and moderate income workers and their families in terms of rising wages and incomes, and reduced poverty. In the event of a serious slowdown, city policymakers need to prioritize how to preserve these economic and policy gains. This challenge will be every bit as important as balancing the budget.

James Parrott is director of economic and fiscal policies at The Center for New York City Affairs at The New School, and co-author along with Michael Reich of “An Earnings Standard for NYC’s App-based Drivers: Economic Analysis and Policy Assessment,” July 2018.