Adi Talwar

John White working on a Build It Back site in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, where he is a lifelong resident..

October 29 marks three years since Superstorm Sandy wracked the Atlantic coast. The storm was the second-costliest in United States history, causing over $70 billion in damage, displacing hundreds of thousands from their homes, and resulting in over 100 deaths. Missy Haggerty, a lifelong resident of Brooklyn’s Sheepshead Bay, remembers the shock of watching her neighborhood disappear underwater.

“It happened so fast,” says Haggerty, “one minute we see water bubbling up from the drains in the street, the next moment we hear something like a waterfall coming down the avenue.” Haggerty gestures above her head as she describes the deadly surge, “It got up to eight feet—before we knew what was happening, our cars were washing away.”

For Haggerty and thousands like her, the past three years have been a painful saga of recovery. A single mother who lost her job as result of the storm, Haggerty spent a year cobbling together funds and supplies to restore her home to a livable state. She says relief agencies were slow to arrive to Sheepshead Bay, but she was determined not to let her neighborhood be overlooked. “You can’t wait for someone to come knocking at your door with drywall,” says the petite, square-shouldered blonde, “you have to show them your face.” Her quest took her to local and citywide meetings and eventually led her to Albany, where she lobbied for greater aid to her community.

Today, Haggerty is proud of the home she’s rebuilt. The two-bedroom bungalow, originally constructed in 1918, is now freshly-painted and festooned with seasonal decorations. “When Sandy hit, it felt like we’d never recover,” she says, running her polished nails over her 80-pound Labrador mix. Haggerty admits that the recovery is far from complete. Several “zombie houses” on her block have been abandoned to decay, while other neighbors are in various stages of reconstruction. Many victims are plagued by debt thanks to storm-related expenses, while several small businesses in the area have disappeared. Still, Haggerty is grateful to be back home. “It’s finally begun to feel like normal life.”

But Haggerty may have to vacate her home again—temporarily. Her property falls within FEMA’s newly-expanded flood zone map, which was updated after Sandy and nearly doubled the number of homes identified as flood risks. New York City has filed a technical challenge to those new FEMA maps, saying the current risks of flooding from a so-called 100-year storm applies to a smaller area than estimated by the feds. But all parties agree the flood zone is larger than it was believed to be when Sandy struck.

In the future, new construction projects will need to adhere to an expanded set of flood-resistance standards, but properties like Haggerty’s represent a unique challenge. After years of painstaking repairs, Haggerty’s home is now structurally sound, but it sits well below the new flood level. In 2014, the city’s post-Sandy reconstruction initiative, called Build It Back, approached Haggerty with an unusual request: they wanted permission to raise her house nine feet into the air.

Build It Back has made the same proposal to many homeowners with similar properties. The process is intrusive, requiring at least six months and between $80,000 and $100,000 to raise the home, inch by inch, on hydraulic jacks. Once hoisted, the house is placed on a new foundation or perched on flood-resistant pillars. Build It Back offers to perform this procedure on eligible homes at no cost to the homeowner, and when done correctly, the damage to the structure should be minimal.

Haggerty says she was hesitant at first. “I wish they’d come and elevated the houses three years ago when we were already displaced, and our houses were gutted and empty.” Despite the risks of rebuilding below the flood level, Haggerty hadn’t considered elevating her home as an option. “I didn’t have that kind of money,” she explains. “We figured, maybe Sandy was just a once-in-a-lifetime kind of storm. Besides, I can’t afford to move—I’ve had this house for years and my mortgage is low. So, we decided to rebuild.” Haggerty says that it’ll be hard to vacate her home once again. “It’s like we have a wound that’s finally healed—and now they want to open it again.”

A few blocks from Haggerty’s home, Mike Rodriguez, a 68-year-old Vietnam veteran, has been waiting two years for Build It Back to follow through on promised repairs. His snug living room is lined with boxes and building materials, his crossing-guard uniform slung over a stack of wooden panels. Rodriguez halted his personal re-building work in early 2014 when Build It Back alerted him that his home would be “coming up next” for repairs. “They were telling me I had a few weeks to get out—but then nothing happened,” says Rodriguez, “now they’re saying they’ll get to me in March or April [of 2016].”

Delays and distrust

The vague wait times have prompted many Sandy victims to give up on the program, which at its height had 20,937 applicants. Mark Treyger, a councilman from Brooklyn and chair of the Council’s Committee on Recovery and Resiliency, says inefficiency and red tape have plagued government relief efforts since day one. “Bureaucracy got in the way of progress,” Treyger told City Limits. Peter Gudaitis, president and Chief Response Officer at the New York Disaster Interfaith Services, agrees: Build It Back “wasted crucial months” at the outset of recovery. “It was a total debacle at first,” says Gudaitis, “so people started looking elsewhere.”

Resurrection Sandy Relief, headed by Brian Steadman, was one of over forty relief organizations that operated in the immediate aftermath of the storm. Steadman says he wrestled with the dilemma of moving people back into homes that were known flood risks. “Ideally, every house in the flood zone would be elevated,” says Steadman, “eventually, as the city started to come around promoting home elevation, we’d get criticized. Some people told us we were wasting our time and even putting folks in danger. But what else could we do? I don’t have the resources to raise entire homes.” Instead, Steadman and his teams focused on urgent, short-term repairs.

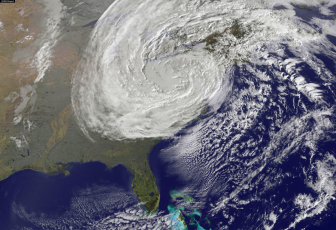

NASA

The Flood Next Time: Three years after Sandy, New York City shows no signs of pulling back from rising waters. Click on the photo to read A Nation-City Limits investigation.

Steadman’s organization, low on funds and volunteers, officially ended its work in the summer of 2015. “The work is far from over,” says Steadman, “Lots of folks still live in unsafe conditions, and many have fallen into debt since the storm.” With grant money drying up, even major organizations like the Red Cross have stepped out of direct assistance, leaving Build It Back as one of the only options for the hundreds still in need of help.

And Rodriguez, despite his doubts, is in no position to refuse help. He and his wife Catherine were dropped by their insurance company shortly before Sandy hit. “It seemed out of the blue, but I guess they knew what was coming” says Rodriguez, shaking his head at the memory. Rodriguez applied three times for FEMA assistance, eventually receiving $17,776.12, but he’s had to rely heavily on his retirement funds to cover the nearly $70,000 of expenses incurred so far. “We’re getting by, but I could really use the supplies and labor that Build It Back is offering,” he says.

Despite their need, many residents of Sheepshead Bay are vocal about their mistrust of the city program. “I hope they’ll come through, but I’ll believe it when I see it,” says Rodriguez.

Some of the worries about Build it Back revolve not around its timing, but whether its plans are a good fit for the neighborhood. For example, says Haggerty, when Build It Back first presented their plans for her block, they failed to address the unique architecture of the homes in question. “Many of the row houses are connected to each other,” explains Haggerty, “A lot of them have to be raised at the same time, or you can’t raise them at all.” Haggerty shakes her head, “They had no idea about what our blocks even looked like. I told ’em, you gotta come down and walk around and see for yourself what we’re dealing with.”

Still, Haggerty says things have improved under the de Blasio administration, and she’s impressed by recent efforts from officials like Amy Peterson, director of the Mayor’s Office of Housing Recovery, and Treyger to engage at the ground level. “Amy’s been down here a couple times,” says Haggerty, “I know there are folks over there that are really trying to make this work.”

The numbers seem to agree—between September 2014 and August 2015, the Build it Back program nearly tripled its number of “construction starts”—now up to 1,612—and brought its total of completed homes up to 906. The program has recently hired more personnel and increased its allowance for temporary housing reimbursements as well, and as of August had issued 4,222 checks for a total of $80 million in disbursements.

Sticking together

Haggerty has agreed to let Build It Back raise her home, and she has been enlisted by the program to recruit her neighbors to enroll as well. She feels she’s the right person for the job. “My family has been on this block for three generations. I know every person, I know every house.”

Rodriguez has begun to advocate for Build It Back on his own street, too, walking door to door with forms and patiently explaining the application procedure. “People are glad to hear there’s still help available,” says Rodriguez, who has helped more than half his block enroll in the program. “We need to stick together, just like we did when the storm hit.” Haggerty and Rodriguez now coordinate their efforts, keeping tabs on community needs, consulting contractors, and keeping in touch with Build It Back officials. “It’s like the Mets winning,” says Haggerty, “We’re a team, and everybody’s gotta play their part.”

In Sheepshead Bay, insiders like the Haggerty and Rodriguez will be crucial to the success of the program, says Steadman. “The people on the ground understand their needs best,” he says, “drive-by charity never works.” Erica Lowry, Senior Director of Long Term Sandy Recovery for the Red Cross, agrees. “The lingering effects of the storm will take years to address. In every recovery process, it is local, grassroots leadership that makes the real change happen.”

Signs of that change are visible. At one site on Brown Street, foundations are being laid for a new, flood-resistant home to replace one ravaged by the storm. There, 50-year-old Sheepshead Bay native John White is hard at work. White, like many, faced unemployment after Sandy, but he’s since been hired by Build It Back to assist the build.

White lost his home—and his dog—in the storm, and has been living in a makeshift shelter on his property ever since. He enrolled in Build It Back in 2014 and now waits to hear when the program will begin restorations on his property. “I’m keeping busy,” he gestures to the active construction site behind him, “and hopefully it won’t be too long before my turn comes around.”