Adi Talwar

Amoy Bailey broke her leg two months ago, forcing her to miss work, fall behind in rent and join the line at Bronx Housing Court.

This is the second part in a four-part series on housing court.

To read the whole series, click here.

* * *

When the Bronx Housing Court was built in 1997, then-Mayor Giuliani declared it “a proud moment” in Bronx history.”

“The new courthouse will restore a level of distinction and significance to Housing Court proceedings that was absent in its previous location,” he said in a press release account of the ribbon-cutting ceremony. More than just a new state-of- the-art building equipped for the needs of the 21st century, Giuliani called it a “symbol of the borough’s resurgence.”

Fifteen years later, it is more of a symbol of stubborn and persistent need in a borough that seems unable to shake housing as its achilles heel.

The 13 courtrooms of the 94,000-square-foot Housing Court on the Grand Concourse cannot withstand the demands of rising costs gradually pushing its way north. Nearly all Bronxites who end up in housing court do so because they are brought there by their landlords for nonpayment of rent. In 2013, more than 83 percent of total petitions filed in Bronx housing court were for residential non-payment.

Landlords can also file “holdover” cases against tenants to get them out of apartments for which they don’t have a lease or have violated one. Tenants can sue their landlords for outstanding repairs in an “HP action” at a separate window — though only about 2.5 percent of cases filed in Bronx Housing court in 2013 were this type.

Giving and getting “answers”

After navigating their way into the courthouse, tenants facing a non-payment proceeding will line up again once they get past the security screening. This time, they will wait in a much slower line to file their “answers”—the court term for their defense against their landlord’s claims—at a window in the lobby. This can easily take an hour and is where young children and babies, along with their parents, begin growing impatient and agitated.

Some will get to the Answer window and learn it’s too late to file one because there’s been a Default Judgement for Eviction against them. They will likely join the others carrying Warrants for Eviction gathered in the dreaded Room 230 Order to Show Cause Room, where they’ll take a number from a dispenser and wait for a judge to grant them a reprieve.

Before starting a nonpayment proceeding, a landlord first has to send a three-day notice requesting the outstanding balance and notify the tenant that if they don’t pay it they will wind up in court. There is no minimum amount for which a landlord can start a nonpayment case, and the denominations can sometimes be very small. (There is nothing wrong with that business practice, says Mitchell Posilkin, the general counsel for the landlord group Rent Stabilization Association, who says a landlord figures “‘If I have a deadbeat, I need to know sooner than later.'”)

After the notice is sent, the next step is for the landlord to file a petition with the clerk to officially begin the case.

Besides rent, landlords can use court papers to seek additional security deposits to cover a rent increase during the tenancy, as well as lawyers’ fees, late fees, and charges for incidentals like air conditioning.

If the tenant does not file an Answer of Petition within five days of service, the landlord can seek a default judgment for eviction. But the paperwork sent to tenants does not make it clear when the clock on the five days begins ticking, and the fact that the five days includes weekends is unusual and throws people off.

Clerks help some tenants Answer by doing it for them, but only by asking about some of the formulaic responses listed as potential defenses. It’s hard to blame the clerks for being brusque: This line is also long, and everyone on it is tense. It can take up to an hour to reach the window, and the stream of tenants is steady. Still, even when they are being helped, tenants are processed, rather than actually consulted.

Either way, even defenses that tenants should be able to fall back upon are sometimes not practical to mount. For instance, landlords are supposed to serve papers upon the tenant but Jennifer Laurie, the executive director of Housing Court Answers, called it “pretty routine” for many process servers to “skip that first step.” But while improper service is one of the defenses on the Answer sheet, the process of objecting to service is too cumbersome and risky for almost any tenant handling their case pro se (without a lawyer), she says. And it’s unlikely to come up in the hurried conversation with a clerk on the other side of the glass.

Once a nonpayment case is put on the calendar, it goes to the Resolution Part, which has its roots in the idea that tenants and landlords can come to an agreement before a case is fully litigated.

The vast majority of cases are settled in the long and narrow hallways of the fourth floor by “stipulation” — an agreement between the landlord’s representative and the tenant, which is then approved by a judge.

Help hard to find

With a little help, many tenants could avoid getting evicted or agreeing to a stipulation in which they promise to vacate their apartment or pay more rent. But at Bronx Housing Court, help seems to be both everywhere and nowhere at once. The people there to help can be gruff and impatient. Doors offering legal services are often locked.

Kathryn Neilson, a housing attorney at Legal Services in the Bronx, which has a satellite office in the Bronx courthouse, says about 50 percent of people come through some kind of referral. That may be why—despite the fact there are several offices designed to help tenants in the housing court—many people who show up without help don’t end up finding it.

“I always have to remind myself that we’re serving this tiny, tiny fraction of people,” she says.

While there are multiple offices inside the courthouse meant to help tenants — from Legal Aid, to Legal Services, Housing Help and Housing Court Answers — the problem, says Laurie, is that “The intake process is very limited.” Most people will not get help.

Wanda Candelaria didn’t. She had been to court multiple times and filed two Orders to Show Cause without the help of an attorney. On the last day of 2014, she came knocking on the door of Legal Services, where she had been referred by Catholic Charities, complaining that nobody had returned her messages. Turned away again that day, at least for the time being, Candelaria, who is legally blind, held her court papers close enough to her face to touch her nose, while sitting near the Housing Help office that had emptied for the break for lunch.

“What I’m afraid of is that if I go before the judge without legal representation he’s just going to be like, ‘You know what, you’re evicted,'” she said. The last time she was in court she was able to get her eviction stopped, after one failed attempt, by a stipulation written by a judge, which gave her until the 31st to pay thousands of dollars in rental arrears. She’d been chasing down a loan from the Human Resource Administration to pay them, but hadn’t succeeded. And so she was back, alone again, asking for more time.

Those working with tenants in Housing Court say it’s the people who come without attorneys or the backing of any organization who are most lost through the housing court process. Particularly imperiled are those who make just too much money to qualify for help. “I think it’s very hard for people who have their incomes … sort of at the moderate level, have two members of the house working fast food or in the service industry, not jobs with a lot of security or benefits, and live paycheck to paycheck, who do not receive any public benefits and are not a priority list for the legal services contracts,” Laurie says.

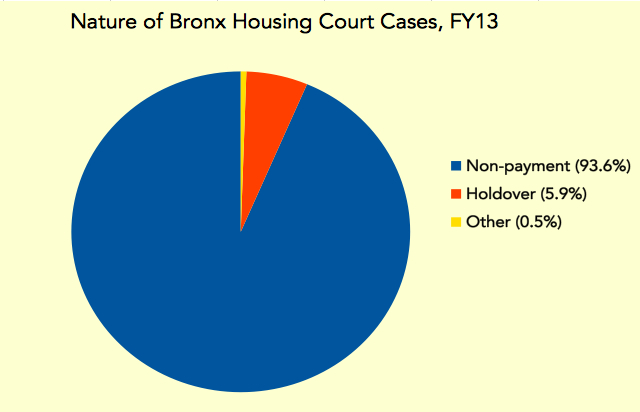

Housing Court Data

While tenants can take landlords to housing court, that almost never happens. The overwhelming majority of cases are filed by landlords seeking rent. Most of the remainder are filed by landlords trying to evict someone who was already supposed to leave.

The lawyers

Upstairs from the courthouse lobby where Housing Court Answers stands, the landlords’ attorneys conduct the cacophonic symphony of wheeling and dealing taking place in the hallways, like bees working a honeycomb, Bronx style — shouting names up and down hallways and staircases in search of the tenants that belong to each of the day’s stack of files.

There are very few white people, except for the attorneys, judges, court officers and clerks. So few that a white person may be mistaken as someone who belongs to this class of workers just for roaming the hallways or entering a courtroom.

Some lawyers handle as many as 20 cases at once, zipping in and out of courtrooms with their bundles, joking with the clerks or court attorneys and ruffling quickly through case files at the front of courtrooms.

As long as both parties check in by 11 a.m. for a 9:30 a.m. calendar call, landlord’s attorneys are free to attend to multiple cases in courtrooms on various floors. Tenants, who themselves may be missing unpaid days of work, are sometimes asked by the landlord’s attorney to wait for their case to be called.

Bronx judges hear about twice as many cases every day as their counterparts in other boroughs, except for Staten Island, the CASA report Tipping the Scales found. Some worry about what Christian Fitzroy, a CASA tenant leader, called the “camaraderie” between court attorneys and landlord’s attorneys that leads to a “more sympathetic relationship with the lawyers than the tenant.” But Posilkin counters that courthouse “regulars” are bound to their reputations, and that would leave little room for what he called “slick lawyering.” He said that Fern Fischer, the deputy chief administrative judge for New York City, had instructed judges to review all agreements between landlords and tenants carefully before signing them.

Making deals

But most tenants will speak to their landlord’s lawyer long before they ever come into contact with a judge. Tipping The Scales, a report of tenant experience in Bronx Housing Court, put out by New Settlement Apartments’ Community Action for Safe Apartments (CASA) and the Community Development Project (CDP) at the Urban Justice Center in 2013, found that three of every four tenants who spoke to a judge found it helpful, but 40 percent of tenants never did and 53 percent of tenants were asked to pay the rent they owed or make a settlement in the hallway before entering the courtroom.

These sideline meetings are where tenants without representation can fall prey to their adversaries in the hallways, signing agreements that may look from afar like successes statistically because a resolution was reached, but are not necessarily good for the tenant, who is not required to negotiate with the landlord’s attorney but usually doesn’t know that. A tenant can request to skip that step and speak directly with a court attorney, but that is not presented as an option, and it is rare for anyone to inquire.

CASA’s study found that three-quarters of people surveyed did not help write their stipulations, meant to be an agreement between the two parties. Those findings were corroborated by dozens of observations of dealings outside the resolution part of Bronx housing court, despite recent reforms that seek to address some of these issues.

“They use their demeanor and the way they talk to people and the pressure they’re under, to intimidate tenants,” Laurie says of the landlord lawyers, creating an “atmosphere of sort of bending the tenants down to the landlord’s will.”

Landlord lawyers might offer tenants stipulations they cannot reasonably be expected to meet, especially if they are waiting on benefits the courts know take sometimes months to process. That will likely bring them back to court at the end of the month to ask for more time to pay, or give the landlord reason to restart a case against them.

The “stip” itself can be a trap.

One young couple in the co-op part of housing court on a recent day was weighing whether to sign a stipulation. The lawyer wanted to know simply “how much do you owe and when you’re paying it,” Hakeem Giscombe, 24, explained as he stood outside the courtroom with his girlfriend, Pamela, 21, repeatedly opening a green folder with court documents inside and then glaring up at the glass-encased court calendar as though he were checking something. “He says that’s all he’s authorized to do.”

Giscombe says his father recently died and that he became aware of rental arrears on his father’s co-op apartment in the course of taking over the lease. He went to HRA for a One Shot Deal, and was approved. It was there that he was advised not to sign any stipulations once he got to court.

The lawyer’s representative had written up a stipulation which gave Giscombe a deadline of 45 days to fork over more than $6,700 in arrears and also charged him late fees.

After walking away, the attorney returned to hastily explain to Giscombe and his girlfriend that they could get their own attorney if they wanted and didn’t have to sign the stipulation he had offered them. But the information didn’t stick and Giscombe was confused.

“That’s the guy representing me, Lazarus,” he said when asked to identify the role of the person he had been speaking with. No, he corrected himself. “I think that’s the lawyer they appointed to deal with the situation.” With some nudging from his girlfriend, he acknowledged that it was the landlord’s attorney. “I think he’s just trying to back me up on this,” he said. “He just doesn’t know how.”

Maybe. But the same can be said of the many tenants who show up because they are stretched thin with commitments and then find themselves crushed by an unforeseen dilemma.

Esmerlin Valdez, the baby-faced mom with short jet-black hair we met waiting outside the courthouse, says her 12-year-old daughter was on the wrong path, so she sent her away to live with her paternal grandmother. Between paying for her daughter’s school fees and a loan to her brother, she calculates shelling out $1,000 every two weeks. The burdens began to weigh her down and each month the same rent bill of $810 was due.

Valdez began making partial payments on her rent in May, she says, and then she spiraled into a deep depression.

She said she was rejected for a One Shot Deal from HRA’s Bronx office twice because she made too much money as a $49,000 a year staffer at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, even though she had not been in the hospital or collecting that salary. In order to get the assistance, though, she would have to be working to prove she could pay back the loan but still not earning too much to disqualify her.

By the time she showed up for her October 31st court date, she had been back to work two days that week and was dressed with the thought that she would make it in after her court appearance.

Valdez approached the clerk, who informed her pleasantly that her case was not on the calendar.

“Did you serve the landlord’s attorney an Order to Show Cause?” she asked of the paperwork that she would need to file and have signed by a judge to at least delay her eviction. Valdez had not. “You have to serve them,” the clerk instructed.

Valdez tried to explain her forgetfulness to the clerk. “During that time I was hospitalized and stuff,” she said. She was told to go back down to Room 230 to start another Order to Show Cause. She also requested proof of her rental arrears from the landlord so that she could apply again for a One Shot Deal.

The clerk helped her track down the lawyer but he said he didn’t have her file and couldn’t help that day. During the lunch hour, Valdez teared up by the copy machines while swiftly reproducing for the HRA paperwork showing her application is pending.

She handed the clerk her an Order to Show Cause, with the documentation attached, and the clerk informed her that there was already a marshal’s order in place to carry out her eviction. At 3 p.m., the clerk explained that the judge sitting beside her would not sign the Order to Show Cause to stop it.

Only after she was dismissed by Judge John Stanley did Valdez ask him to please look at the file again to see that she had been back to HRA but needed a rent record she could only get in court.

He checked the paperwork and told Valdez to go back Room 230, where—finally—her stay of eviction was signed. She would have two more court dates, and would have to file a third Order to show Cause before being approved for the One Shot Deal five months after applying for the third time.

Down in the lobby, a sign taped up near the elevator bank posed the perfect question for the court’s visitors. “Are you feeling overwhelmed?” it asked. But the flyer was from the Bar Association and aimed at stressed-out attorneys, prompting Jessica Hard, who was working the Housing Help desk that morning, to crinkle her face with disgust when she saw it.

The growing and disproportionate numbers of Bronxites who experience housing insecurity would seem more a more appropriate audience to target for help.

“That’s insulting to people,” she said.

This is the second part in a four-part series on housing court. To read the whole series, click here. The series was made possible through the generous support of the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

2 thoughts on “Tenants Battle Landlords and Bureaucracy in Housing Court”

This has been a mess since forever. No mayor will ever be able to straighten it out.

Q. When the Judge refuses to hear a Holdover….without Tenant depositing rent in an escrow….what to do?