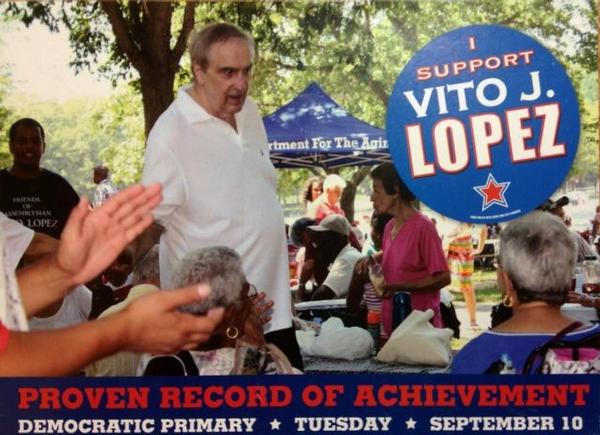

Photo by: Lopez campaign

A flyer from Vito Lopez’ failed comeback attempt this fall, which saw the former assemblyman and one-time Democratic chair lose a primary race for an open Council seat—one being vacated by a former aide turned rival.

On a once-neglected plot in Bushwick, Brooklyn, there’s a quiet neighborhood of homes. The decayed former brownfield site of the Rheingold brewery now boasts 58 affordable duplexes, four three-family homes and 30 condominiums that are also 100 percent affordable, along with 88 co-op units and 272 subsidized apartments. A spot that embodied the neighborhood’s plagued landscape now has a tidy neighborhood of houses built in a Dutch style and a brick senior center on the ground floor of apartments with solar panels on the roof.

The neighborhood turned around through the political muscle of Vito Lopez, a fallen Brooklyn giant. He resigned as chairman of the Brooklyn Democrats in August of 2012 and gave up his long-held State Assembly seat in May after sexual harassment allegations—like the night he grabbed a female staffer’s hand in a bar and counted to 60 while looking the stricken young woman in the eye, according to a state ethics committee report.

Lopez lost a City Council race this fall after a career in which he had turned a remote and notorious area of Brooklyn into the home base of a political empire by helping the needy and mobilizing his beneficiaries. The ethnic politics of Williamsburg and the harassment allegations took down the leader of the Kings County Democrats. Yet Lopez also cemented a lasting legacy through the brick and mortar housing now present in the former vacant lots of Bushwick.

“People who paint him as some sort of a machine politician character—I think that they’re wrong,” says Baruch professor Nicole Marwell, whose 2007 book “Bargaining for Brooklyn” chronicles the complexities of Lopez’s impact on Brooklyn. “Vito’s personality may lend itself to that portrayal but it’s not the core of what he did.”

Over nearly three decades in power, Lopez, 72, amassed resources and rivals. He won a seat in the Assembly in 1984 as the founding executive director of the non-profit Ridgewood Bushwick Senior Citizens Council. One of the most powerful politicians in the state, whose headquarters was a stop for gubernatorial hopefuls and presidential candidates, Lopez rose to become party leader for Brooklyn in 2006. The longtime chairman of the Assembly’s Housing Committee steered funds back to Bushwick that turned 1,800 burned-out lots into new housing and senior centers. That’s why Lopez’s constituents usually re-elected him with 90 percent of the vote—at least according to Lopez.

“They see the apartments, the nursing homes, the youth center and they go there,” Lopez says. “That’s something that they know.”

But his victories came at the expense of others—non-profits that weren’t Ridgewood Bushwick, competing politicians and even a local Catholic church. North Brooklyn mainstays like Councilwoman Diana Reyna and Brooklyn Legal Services counsel Marty Needelman started out working hand-in-hand with Lopez, but they both actively opposed him before there were any sexual harassment allegations. Indeed, Lopez’s fall may have begun not with the charges of creepy behavior, but with a rash of investigations of Ridgewood Bushwick and the massive salaries earned by Lopez allies employed there—a scandal that went to the roots of Lopez’s political power.

This fall, Reyna and Needleman were part of a coalition who backed Antonio Reynoso, Reyna’s former chief of staff, in his successful City Council run against Lopez. Reynoso is also a founding member of the anti-Lopez New Kings Democrats, a thorn in Lopez’s side within the party structure since 2008. There’s a sense of relief among Lopez’s foes now that the colossus who dominated area politics for three decades looks finished for good.

“That’s an era I’m so glad is over,” says Barbara Schliff, housing director of Williamsburg’s Los Sures, an advocacy group Lopez tangled with for years.

Vito Lopez lost his last chance at public office in September, when an upstart backed by his rivals beat him. (Video by Dominik Wurnig and Tobias Salinger)

”Helping people”

“Helping people” was Lopez’s initial motto for Ridgewood Bushwick. The Bensonhurst, Brooklyn native with both Italian and Spanish roots trained in Yeshiva University’s community organizing program and in 1970 began working at a city senior center on Stanhope Street in Bushwick.

He won over the elderly patrons by combining his energetic study of government programs for poor people with active pursuit of them alongside the seniors. Just three years later, he founded Ridgewood Bushwick and won a contract to run a center that is still prospering. And today the gaunt yet massive, cancer-diagnosed Lopez still clearly delights in reeling off his significant good deeds: Thanksgiving and Christmas feasts on Stanhope Street for thousands—often paid for by Assemblyman Lopez’s discretionary funds—and concrete evidence—like Ridgewood Bushwick’s affordable stock of 2,000 units plus 3,000 other low-cost private residential units fixed up through city, state and federal programs—show how the original motto fits.

“He helped thousands and thousands of poor, indigent people and low-income people get affordable housing,” says Brooklyn Assemblyman James Brennan, who joined the Assembly the same year as Lopez.

The 2,740 units of housing are only part of Ridgewood Bushwick’s impact in Bushwick. The list of over 350 new two-family and sometimes three-family homes is not the full extent of state and city housing partnership houses, according to Ridgewood Bushwick housing director Scott Short, who shared a list of the social service non-profit’s housing and senior facilities. (Graphic by Tobias Salinger and Amanda Dingyuan Hou)

Lopez positioned Ridgewood Bushwick for these achievements through mastery of the contract bidding process early on. Soon after the senior center was launched, he and his increasing staff won bids in a city Department of Housing Preservation and Development community consultants program. State and federal aid like a rent-control program for seniors and Section 8 subsidies also built up the organization. Later, Section 202 funds, another U.S. Housing and Urban Development program, provided funds for new senior housing and a menagerie of sources backed the 240-bed Buena Vida Nursing Home that remains the biggest employer in Bushwick.

For constituents like Viola Sacheli, 68, who frequents Ridgewood Bushwick’s Hope Gardens Senior Center, Lopez’s accomplishments obscure the embarrassing headlines.

“What politician doesn’t do something under the table?” Sacheli says. “That’s how I look at it. In my eyes, he has done a lot for the poor people.”

Lopez displayed considerable skill right from the start in gaining staff through a federal work program called the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act that reimbursed local governments and nonprofits for one- or two-year staff stints, according to John Dereszewski, who served as Bushwick’s Community Board 4 inaugural district manager in 1977. Both Christiana Fisher, who would serve as executive director for 21 years, and Angela Battaglia, a current commissioner at the City Planning Commission and Lopez’s longtime girlfriend, first worked at Ridgewood Bushwick through the federal funding.

Mastering Albany

When Lopez went to Albany, he worked his way up the Assembly’s Housing Committee, eventually becoming chairman and always searching for funds to build more affordable units.

He backed both the Neighborhood Preservation Program, a state program that makes seed investments in community housing organizations like Ridgewood Bushwick and Los Sures, and the Housing Partnership, a public-private push to build residential ownership homes that netted Bushwick 1,500 new units. When Governor Cuomo’s 2009 budget cut some of the funding for neighborhood housing organizations by $2.1 million, Lopez restored the money through his own discretionary funds, records show. The preservation program helped 147 housing organizations obtain more than $448 million in financing through an initial $8.1 million investment over the last two years, according to an annual report from the state housing department.

“From almost day one he was a serious legislator,” says Dereszewski. “He could probably paper his wall with laws that he passed.”

Lopez legislation encouraged property owners to build up the cheap housing stock through loft units and tax incentives. The 2010 loft law expanded legal, rent-stabilized conversions to former manufacturing sites in Bushwick and Williamsburg after Lopez agreed to exempt certain industrial zones at the urging of the Bloomberg Administration.

Lopez also greatly expanded the areas of the city covered by the 421-a tax program—which gives real estate developers a tax abatement if 20 percent of residential units in new projects are affordable—through a 2007 law. The program, which gets renewed every three years, has its critics. But Lopez was a steadfast supporter. “Without that law, you would not have to build one unit of affordable housing,” Lopez says. “And that’s a fact.”

Lopez holds forth in opening statements at a 2010 Housing Committee hearing on an extension of the 421-A tax credit.

The full scope of the funds Lopez helped Ridgewood Bushwick acquire over his time in office is hard to fathom or quantify. Ridgewood Bushwick received $156.2 million from government grants between 1998 and 2011, according to its federal tax documents, and its city contracts between 2010 and 2014 come to $32.5 million, according to a database from the comptroller’s office. But the city Department of Investigation found that the firm “held (or was slated to be awarded) over $75 million worth of city contracts” in June of 2010 in a report from that year. The organization has developed extensive and continuing working relationships with a variety of government agencies.

“We get stuff done when we say we’re going to do it, and it’s not easy,” says Scott Short, housing director of Ridgewood Bushwick.

Lopez’s ability to steer funding created both political clout and campaign resources. Politicians of all stripes stopped by Ridgewood Bushwick for ribbon cuttings, annual picnics and public appearances. Gov. George Pakistan once pitched health care proposals from Stanhope, and Vice President Gore visited during his 2000 campaign, to name only a few. Council Speaker Christine Quinn’s reported gift of chicken soup—delivered to Lopez when he was ailing one time—was dwarfed by the more than $4.1 million in discretionary funds Ridgewood Bushwick has received over the past five years from Quinn and other Council members, according to city records.

And Lopez’s area of expertise—housing—coincided both with the interests of his Bushwick constituents and that of people who built the housing.

“There would be all kinds of money to be made building Ridgewood Bushwick housing, and they had lots of contracts,” Assemblyman Brennan says. “So the construction contractors would make lots of contributions.”

The Bluestone Organization, the developer for the partnership houses at the Rheingold complex, donated $21,700 to Lopez over the past 13 years and another Ridgewood Bushwick contractor, Strategic Development and Construction Group, gave $16,450 over the same time period, according to campaign finance records.

That doesn’t mean that Lopez especially needed a lot of campaign money to be re-elected. From the Bushwick Democratic Club on Kickoff Avenue, his political staff and ranks of willing volunteers coaxed votes using lists they kept and updated themselves, according to Marvell’s account. Lopez sailed to re-election 14 times by counts like 25,733 votes out of 27,265 cast in the district in 2008. Prospective and sitting mayors understood they could count on him delivering votes if they got his support. Lopez thrived off the connection between votes and contracts, and Marvell’s transcript of a 1999 speech shows that he was express about it: “A political favor means that when there are two hundred requests for public money, and only two get funded, the people who are owed a favor get one of those two,” Lopez said at a meeting following a round of judicial elections.

His attributes would prove irresistible to the Brooklyn Democratic Party when Assemblyman Clarence Norman stepped down as county chairman in 2005. Lopez pressed his IOU’s and accomplishments and became the most powerful politician in the borough.

“Housing is such a scarce resource, and affordable housing is such a scarce resource, that in hindsight it makes sense that the one who is chair of the Housing Committee in Albany becomes county leader,” says Marwell.

Remaking Rheingold

The Rheingold brewery site certainly added to Lopez’s reputation on the way to that victory. The design of the impressive complex in western Bushwick close to the Williamsburg border emerged from an October 2000 design conference—known as a “Charlotte”—organized by Lopez and the city Department of Housing Preservation and Development. International brownfield experts, government agency representatives and area residents teamed up for visits to the dilapidated 6.7-acre site and collaborative workshops over three days to come up with plans for the complex.

Lopez arranged to pay the tab of $97.1 million through nine government and private sources such as Goldman Sachs and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, according to a 2006 best practices case study on the Rheingold site by the U.S. Conference of Mayors.

“I pride myself on the planning and bringing in the comprehensive development, not just doing whatever is available,” Lopez said.

Construction crews broke ground on the first phase—62 multi-family homes, 30 condominiums and two six-story, 93-unit apartment buildings—in 2002. The $228,000 two-family partnership homes affordable to families earning between $45,000 and $75,000 a year allowed new home owners to buy one unit and rent the other, and 75 percent of homes went to neighborhood residents, with 10 percent set aside for police officers. The apartments for people with incomes below $42,000 rounded out the complex that forms a marked contrast with the public housing towers just down Bushwick Avenue.

The completed development where dog carcasses and drug addicts used to collect won the 2005 Phoenix Award for environmental restoration and the 2009 John M. Clancy Award for socially responsible housing. And the archway between two of the brick buildings that reads “Thank You Assemblyman Vito Lopez” does reflect widespread opinion.

“People would walk by and say, ‘Oh, they should do something with this,’” says David Occasion of the Rheingold Homeowners. “And Vito Lopez did do something with it. So a lot of credit goes to him.”

A triangle stokes tension

But that credit doesn’t carry currency for people across the Williamsburg boundary. Lopez negotiated to include the Rheingold rehabilitation in a Sept. 15, 1997 memorandum of understanding between Mayor Giuliani, Lopez and Council Members Victor Robles and Kenneth Fisher. The agreement carved up much of Williamsburg for future zoning changes, allotted funds and resources for Los Sures and the Satmar Hasidic United Jewish Organizations and planned future actions on a 30-acre, city-owned site known as the Broadway Triangle Urban Renewal Area.

That document shaped bruising rezoning fights that stoked the tensions between Williamsburg’s Latino and Hasidic communities and paved the way for the 2005 push to upzone the Greenpoint and Williamsburg waterfronts, according to Marwell. Lopez was able to get the Rheingold site for Ridgewood Bushwick in exchange for the United Jewish Organizations obtaining the former home of the Schaefer brewery in Williamsburg. (Requests for comment from Rabbi David Niederman of the United Jewish Organization were unsuccessful.)

And the finite units the 1997 agreement awarded to Los Sures paled in comparison to the wide swaths of Williamsburg and Bed-Stuy that the city awarded to United Jewish Organizations (UJO). By executing the agreement, Lopez sided against the Latinos who had been pressing and winning housing discrimination suits against the city since the 70’s.

“He just decided to support Giuliani, and that was it,” says Schliff of Los Sures. “Everyone was supposed to fall in line but it didn’t work out that way.”

1997 MOU (Text)

Later years would show this 1997 memorandum of understanding between Mayor Giuliani, Lopez and Council Members Kenneth Fisher and Victor Lopez served as the blueprint for Williamsburg’s future.

Divisions between Lopez and the area’s Latinos—which had started to appear with the emergence of U.S. Congresswoman Nydia Velázquez and the estrangement of Lopez’s former chief of staff, Councilwoman Reyna—emerged most prominently over the eventual plans for the Broadway Triangle. The city’s proposals for the first three affordable apartment buildings “perpetuate segregation,” according to a December 2011 ruling that blocked construction of the buildings by Judge Emily Jane Goodman of the New York County court. Her finding that the city had improperly created preferential treatment for Hasidic residents also decried the demographic breakdown at the Schaeffer development.

Where the previous design charrette had been successful at Rheingold, the petition challenging the Broadway Triangle pointed to the exclusion of Los Sures and its allies from this one as an exhibit in the suit filed by Needelman of Brooklyn Legal Services on behalf of 40 community organizations against the development. “The Bloomberg Administration was thrilled they didn’t have to choose between UJO and Vito,” Needelman says. “He gave them whatever they wanted.”

Feuds break out

Needelman and others contend Lopez turned on them in exchange for UJO support in his bid to become Kings County leader, and Needelman’s failed 2005 bid for a civil judgeship previewed the turmoil of the Broadway Triangle case. Lopez’s then-surprising support for Richard Velasquez over Needelman created a dynamic where the Puerto Rican candidate garnered a 90 percent vote among Jewish voters and the Jewish candidate got 70 percent of the Latino votes, Needelman remembers.

“I walked into a kosher restaurant in Williamsburg and I saw Vito sitting with Willie Rapfogel and Rabbi Niederman, which I knew would not be good for my race,” says Needelman.

Closer to Lopez’s base in Bushwick, he feuded with Father John Powis of St. Barbara’s Roman Catholic Church and blocked many of Powis’s attempts to build housing for the poor through Catholic Charities. Powis tried to secure state funding to place new housing in neighborhood vacant lots, an effort which turned him into a competitor in Lopez’s eyes. St. Barbara’s only housing victory, an 85-unit building on Wilson Avenue, came after Lopez tried to flip the project for Ridgewood Bushwick at every stage.

“He wanted control,” says Powis. “He always wanted to be controlling everything. It had to be Ridgewood Bushwick.”

But Powis carried his own influence in Bushwick through his prominent role at East Brooklyn Congregations and several successful activist campaigns against the city, and he helped organize volunteers for Reynoso’s campaign against Lopez all the way through primary day even though he is stricken with Parkinson’s at 80.

“We’re going to do everything in our power, and I’m going to do everything in my power even though I’m sick, to make people know you don’t elect people like this,” said Powis this summer.

Those opposed to Lopez rose in number when a special ethics committee in Albany investigated complaints by his female staffers and assessed Lopez a fine of $330,000 after Lopez resigned. The claims of the women, which a panel of Albany lawmakers upheld in their May findings, amount to a pattern of verbal abuse and obsessive behavior by Lopez. The confidentiality clause in a prior settlement with the first two of the four women now has another former Lopez ally, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, in a suit of his own, but Lopez and his lawyer Gerald Lefcourt deny he sexually harassed anyone. Their responses to the committee’s 8-month probe decry an “inquisition” against Lopez and assert that he never had the opportunity for a fair hearing.

“We ask that each Commissioner consider whether he or she can ethically participate in a process that is so wholly devoid of the standards upon which our system of justice is based,” Lefcourt wrote in an October 2012 letter to the committee.

Lefcourt declined to comment for this story and efforts to interview Lopez, who last spoke with City Limits in August, were unsuccessful.

But Lopez first lost luster a few years prior, when the city Department of Investigation looked into Ridgewood Bushwick and turned its findings over to state and federal authorities. While the July 2010 and November 2011 reports don’t connect Lopez to any wrongdoing, their scrutiny of the non-profit he founded in 1973 and showered with funding as a legislator showed that one now-deceased senior center director misused taxpayer funds and alleged that longtime Ridgewood Bushwick executive director and Lopez campaign staffer Christiana Fisher gave herself a raise under false pretenses. Fisher later stepped down from Ridgewood Bushwick, pled guilty to falsifying documents related to her salary increase, and forfeited $173,169.

Nonprofit empire evolves

Lopez didn’t help his cause by responding with incredulous, quotable tirades when members of the media asked him about the sexual harassment allegations or his connections to Ridgewood Bushwick.

“I have no relationship with Ridgewood Bushwick, that’s been investigated and over-investigated,” said Lopez this summer. Using a term that clearly provoked his ire, he once accused City Limits of being part of “the reform world” looking to oust him from power.

Yet neither the demise of Fisher or Lopez has signaled one for Ridgewood Bushwick. Current CEO James Cameron took over in January of 2012 as part of a city-supervised overhaul of the organization. Ridgewood Bushwick repaid $203,784 that one city agency found it owed and cooperated with a probe of 122 separate contracts for a total of $69 million that turned up only one “poor” rating, a 2011 report found. After the non-profit instituted a management improvement plan, the city approved its fiscal 2011 appropriations. And Cameron, who refers to himself as “the cleanup guy,” wants to set the record straight.

“I mean, they went through this place with inspectors and auditors, looking at emails,” says Cameron. “There was no fraud and no findings that ever resulted in any criminal charges against this organization.”

City agencies that have selected Ridgewood Bushwick for what records show are more than $5 million in contracts for fiscal 2014 declined to comment on Ridgewood Bushwick’s status moving forward, as did the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, the agency tasked with certifying the non-profit’s compliance following the investigations. State and federal law enforcement authorities wouldn’t confirm or deny any ongoing investigations.

The last hurrah

Lopez’s rivals turned into a broad coalition following the sexual harassment allegations. But even with nearly every prominent city and state politician opposing Lopez, the 30-year-old Reynoso prevailed by only 1,654 votes, results from the Board of Elections show. And state Assemblywoman-elect Martiza Davila, who has worked at Ridgewood Bushwick for 23 years, coasted to an easy victory in the race to take Lopez’s former seat.

“I’ll be in Albany bringing down the funding,” she said at a September Bushwick Community Board 4 meeting following the primary. Davila declined requests for an interview.

Longtime Bushwick resident and strong Davila supporter Abdon “Super” Berness, 59, once received a plaque from Lopez after he and Davila turned a vacant lot on Irving Avenue into a thriving community garden. But the caretaker of “Super’s Garden,” a property owned by Ridgewood Bushwick, didn’t support Lopez this year.

“Oh, he did good,” said Berness this summer. “Only for his pocket. I don’t like him.”

While Lopez has made no public appearances following his first electoral defeat, his campaign posters are still taped to the window of the Bushwick Democratic Club, a symbol of his faded but well-evident footprint in the community. The ailing and defeated former party boss’s political career is complete.

But Ridgewood Bushwick continues. There were positive headlines recently with the unveiling of plans to build two 24-unit affordable apartments in Bushwick to strict “passive house” environmental standards. The two developments will achieve energy savings of at least 60 percent without using solar or thermal power and will be the first affordable complexes built to passive specifications in the state, according to Short, Ridgewood Bushwick’s housing director.

With Lopez out of the picture, though, it’s difficult to predict whether Ridgewood Bushwick will command the same influence in the neighborhood and with city agencies.

“Ridgewood Bushwick is making a sincere effort to recast themselves for survival in a sense,” says Dereszewski, the former community board manager. “In many ways, there was not a plan for a kind of a post-Vito Ridgewood Bushwick.”

Some new residents and visitors, who have flocked to Bushwick for the cheaper rent prices relative to other neighborhoods and the neighborhood’s vibrant arts scene, don’t even know Lopez’s name. Photographer and artist Daryl-Ann Saunders said she didn’t know anything about Lopez or Ridgewood Bushwick when she started shooting portraits of people who visit Rheingold’s Diana H. Jones Senior Center in 2010. But her initial shock and revulsion once she started reading the negative headlines of that year began to wear off after she volunteered at the annual Ridgewood Bushwick Thanksgiving feast.

“I actually found myself defending the organization because it was obvious that people didn’t know that much about it,” says Saunders.

And organizations critical of Lopez are in some ways using the model that brought Lopez so much success: political participation after work hours by community non-profits. While hindered by Lopez’s animosity, Williamsburg non-profits like Los Sures and the St. Nicks Alliance have won contracts through many of the same programs as Ridgewood Bushwick. Staffers at such competing organizations—and in Reyna and Velázquez’s offices—contributed to Reynoso’s campaign, collected rent from it and helped get out the vote to beat Lopez.

“There’s organizations that are here that I won’t mention because they’re not-for-profits, but let me tell you: they came out and did their work,” Reynoso said at his victory celebration.

Another Reynoso ally, Churches United for Fair Housing, will be marketing the affordable units in the last phase of the Rheingold site—a 977-unit, 10-building private development with mostly market-rate housing. The number of affordable units—which currently stands at 242—will hinge on negotiations in advance of the development’s imminent final approval.

Over the broad scope of Lopez’s career, there may be just as much to emulate as there is to castigate.

“Why shouldn’t you organize your constituents to make your needs known to officials?” says Marwell. “If you’re well-organized and mobilized, then you should get what you’re asking for.”