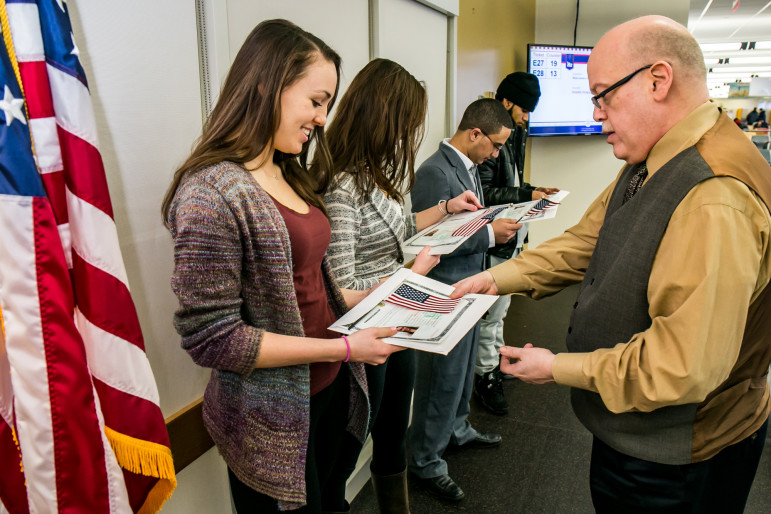

Adi Talwar

Supervisory Immigration Officer Joseph Mormino conducting a Citizenship Ceremony for children at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services offices in downtown Manhattan. left to right- Twin sisters Sarah Siebes and Emma Siebes (17 years) originally from Holland, Rashed Alhanshali (18 years) originally from Yemen and Dario Cruz (21 years) originally from the Dominican Republic, derived their citizenship through their parents.

Sitar Dove had been living in New York City for 15 years when she decided try online dating.

She came to the United States from Trinidad and Tobago in 1995 with her son, Alex, who was two years old. Her husband followed in 1996, but they divorced and he eventually returned to Trinidad. Dove and Alex moved to the Bronx.

By 2000, Dove had naturalized in the U.S. and became a dual citizen. She dedicated her first decade in New York to building a life for her son. But by 2010, she decided to create a profile on Shaadi.com, a popular Desi dating website.

More than 7,000 miles away, real estate agent Suresh Kumar had set up a profile with a friend’s help. Kumar had always lived in Kurukshetra, India.

Dove received a lot of messages once she set up her profile.

“I didn’t feel very comfortable,” she says of the emails. “They all wanted to come to the U.S. When they hear that you’re an American citizen, you get hundreds of emails.”

But Kumar was different. They chatted for nearly a year, until she decided to spend a week in Kurukshetra in January 2010. Once she’d met his family, they decided to get married, and she went back for a month in March for their wedding.

Kumar didn’t interview for his green card until December of that year; initially he didn’t pass, but the immigration officer in India contacted friends and family to confirm his situation. He received his green card in January 2011. Five years later, almost to the day, he naturalized as an American citizen.

The naturalization program run by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services office, a division of the Department of Homeland Security, is massive. In the past decade, the agency has naturalized 6.6 million immigrants, including 729,995 in 2015. The Financial District office alone, which deals with residents of the Bronx and Manhattan, processed 84,000 new citizens last year.

To put that in context, according to the U.S. Census, there were 41.3 million immigrants living in the country as of 2013. That number has continued to grow.

Kumar and Dove’s international love story is unique, but it also highlights the complexity of the U.S. naturalization system. Many who choose to become citizens opt for paths that expedite the process, like marrying an American citizen or joining the military. Those who don’t or can’t choose those paths end up waiting much longer to naturalize. Kumar’s timeline was remarkably short, making his journey from India to the Bronx a rare one.

Much of the public conversation surrounding migration centers on undocumented immigrants, but for many who have legal permanent residency, a bigger question looms: whether to naturalize.

The process can involve a bureaucratic chore, and it requires a significant financial investment. In total, potential citizens pay $680 to apply, according to USCIS Public Affairs Officer Katie Tichacek, though that covers two attempts and fee waivers can be applied. But for many like Kumar, it also reflects a status and opportunity.

On January 8, Kumar became a naturalized American citizen alongside 149 other immigrants, all holding small, plastic American flags given out at the ceremonies. To the side of the room, booths with USCIS agents were set up where people could check in, sign forms and ask last-minute questions. Multiple screens at the front of the room displayed a greeting from Barack Obama.

The ceremony was one of many that occur in and around New York City each week. Some are held in court rooms, others in federal office buildings.

José Fernandez was also naturalized during Suresh’s ceremony. Originally from the Dominican Republic, he says his motivation was to vote. He’s been living in New York City since 1992 and also naturalized on January 8. Asked if he would have been content to stay just a legal permanent resident, he scoffs.

“I think about improvement,” Roche says. “You stay just like that, and you don’t think about something more.”

USCIS officers see the decision to naturalize as intensely personal. Ingrid Stochmal, USCIS’s section chief for naturalization in New York, says people can choose to become citizens for many reasons, and often they aren’t shared with the processing agent. But she says sometimes it’s simply a title people want.

“The reasons would have to be uniquely your own,” says Will Bierman, the field office director for naturalization in New York, “but they would have to be the culmination of an immigrant journey.”

But that journey always completes in the same place: a room full of strangers, with friends and family looking on, and a government official welcoming the new citizens. Bierman says he gets emotional every time “America, the Beautiful” plays at the events. When the song comes on, USCIS staff direct audience members to wave their flags.

“You see those cheesy little American flags waving — that’s a horrible word, cheesy,” Bierman says. “But I get a lump in my throat every time.”

In Jackson Heights, Queens, Camille Samuel runs a citizenship class at the South Asian Community Center.

The challenge her students face the most is learning English well enough to pass the citizenship test. USCIS says that this is the most common barrier for potential citizens.

Jackson Heights is one of the largest immigrant communities in New York City with nearly 62 percent foreign-born residents, according to 2013 Census data.

Many of Samuel’s students don’t have to learn English to get by in their New York lives; they work jobs within their communities, so they have to specifically make time to practice their English. Language is a real barrier to residents in Jackson Heights: 83.1 percent of residents in the neighborhood speak more than just English at home, and 44.1 percent don’t speak English well.

“I encourage them to speak English outside of class, but they’re like, ‘Teacher, we don’t even need English to survive here,'” Samuel says.

Samuel’s citizenship class covers civics, reading and writing, with a focus on speaking. While Samuel doesn’t go through each person’s papers in detail like citizenship officers do, she says they get personal in class to prepare students for the interview, like asking whether they pay taxes.

But beyond the English requirement, Samuel sees the lifestyle for immigrants in Queens as another hurdle to attaining citizenship. The neighborhood’s median income is $49,502, nearly $3,000 less than the city-wide median income. While it’s by no means the poorest neighborhood in the city, Samuel’s students face challenges with respect to adequate living situations.

“They’re either in a one-bedroom or a studio, the whole family — some of them living with another family,” Samuel says. “I think my students are busting it to make it here.”

Samuel acknowledges the benefits to living in the city, including access to services and ease of assimilation into the U.S., but she says it’s a stressful place for people to live.

“It’s a tough life here,” she says. She’s seen students unable to take citizenship tests because they get sick or don’t have time to practice their English. Some have failed repeatedly and can’t pay to take another test. “It’s not the American dream.”

Some are indifferent to naturalization, despite benefits like voting. Because the process is unique for each person, the benefits aren’t necessarily appealing to those who don’t need citizenship for the jobs or lifestyle.

Amanda Low, 27 and a resident of Queens, grew up in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. From childhood, she was well suited to naturalize in the U.S. — her first language is English, and her mother married a U.S. citizen and moved to Jacksonville, Florida, when she was 11. She moved to New York in 2009 as a legal permanent resident, and plans to stay in the country, but hasn’t thought much about naturalizing.

“The main reason is I see no benefit to myself,” she says.

When Low looks at the reasons given by the USCIS for naturalizing, she sees a bunch of factors that don’t apply to her. The only real consideration is the ability to vote, which she has mixed feelings on. She can’t vote in Malaysia because the country doesn’t allow people to cast votes from abroad.

“I can’t vote in the place I was raised in,” she says. “I have no problems not being able to vote here.”

Beyond that, Low is confident that New York will reflect her views, so she doesn’t feel compelled to naturalize just to participate in elections.

“The city is going to vote the way I feel,” she says. “If I was living in the middle of Alabama somewhere, and my vote could actually make a difference, it would be a different situation. But I live in a place like New York where there are a lot of like-minded people that will be voting.”

But the indifference to naturalization runs a little deeper for Low. Part of that decision for her is that Malaysia doesn’t recognize dual citizenship, meaning she’d theoretically give up citizenship in her home country if she became a U.S. citizen.

Low has flexibility in her decision, so she’s able to maintain her green card status without inhibiting her movement or opportunities. For her, it’s less of a requirement and more of a question of how she identifies — and for now, that’s as a Malaysian living in New York.

In 1995, when Dove first arrived in New York, she lived with her sister and her brother-in-law, who had first come during Ronald Reagan’s amnesty program for undocumented immigrants in the mid-1980s. Once was living with them, she wasn’t happy. It was a tight space for all of them, and the culture wasn’t what she was used to.

“When I first came here, I wanted to go back home, honestly I did,” she says. “It wasn’t the bed of roses. It was a struggle for me. But I would not let myself go back home to let my friends laugh at me. I wanted to make it in America.”

She was working 12 hours per day, six days per week, and earning only $200 each week at a beeper store in her neighborhood. She was working off the book, and earning only $2.75 per hour.

During her first attempt at becoming a citizen, she couldn’t afford a lawyer. The immigration officer didn’t give her a visa, he said she’d have to come back. So, despite the costs, she eventually hired a lawyer, convinced she wouldn’t pass the citizenship test without one.

“You cannot just file the paperwork without having a lawyer,” she says. “The immigration officer will just turn around the questions and ask you things that sometimes you cannot answer.”

Dove did pass, even though her husband didn’t. She moved to the Bronx with Alex, then 5, to Clason Point. She took a job as a manager at an electronics store, where she’s worked ever since. She focused on her life with her son for the next ten years.

Despite Dove’s financial challenges, she had a few advantages that many do not: with her sister in the U.S., she didn’t have to find her own apartment; and she already spoke fluent English, the national language of Trinidad.

For others, establishing within the U.S. can be an incredible process. For some, it takes decades to naturalize.

The USCIS requires that applicants have been permanent residents of the U.S. for five years, or three years if they’re married to a U.S. citizen or served in the military. Bierman implies that the wait is deliberately long, allowing people to learn English and establish a commitment to their American citizenship.

No matter what influences people, the decision is one that people have time to think about. Potential citizens have to wait years before they can sit in a courthouse and hold that miniature flag. They have to perfect their English skills and hone their knowledge of American history. They have to display “good moral character,” or pass a background check, and be willing to denounce their home country by reciting the traditional Oath of Allegiance, which is more ceremonial than literal.

“It’s not a mindless process,” Bierman says. “It’s not something you do on a whim.”

When Kumar first came to live with Dove, he was working in a parking garage. Then he started driving — first for Uber, then for Carmel, and now for Dial 7. His goal is to start a business importing Indian jewelry. He just traveled back to India for a month to set up the business.

“My joy knows no bounds,” he says, describing his initial feeling as a U.S. citizen one month in. For him, a big benefit of his citizenship is his ease of travel, which is important to carrying out his business plan.

For Kumar and Dove, that’s what the U.S. represents: challenge, but opportunity. Home is where they go to relax, but New York is where they create the life they want — and in New York, they’re in good company.

“There are so many activities here,” Dove says. “There are places to go, things to see, people to meet. This is a multicultural country where you meet different ethnic groups of people.”

Adi Talwar

Supervisory Immigration Officer Joseph Mormino handing Sarah Siebes a certificate of citizenship as Sarah’s twin sister Emma Siebes, Rashed Alhanshali and Dario Cruz look on.