‘We need more parents to run so that each CEC’s economic diversity reflects that of the district. Without such diversity, whole swaths of a school district may be voiceless.’

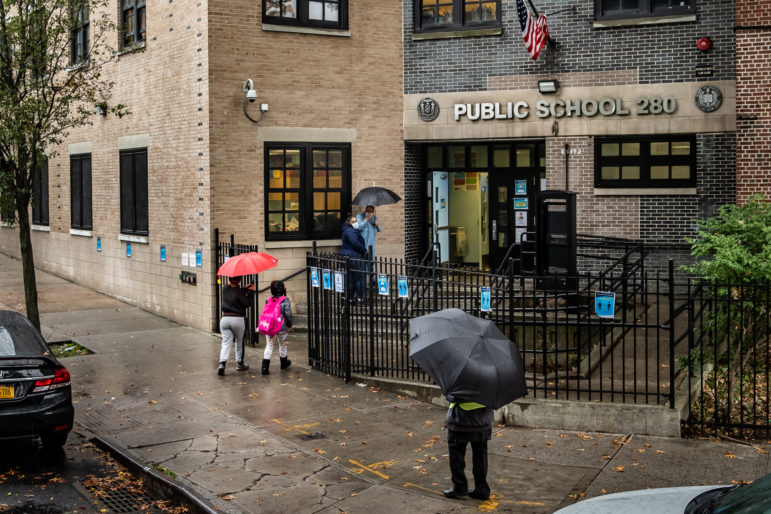

Adi Talwar

P.S. 280 in the BronxAs an education advocate and public school parent, every day I see voiceless parents and students with a strong desire for change in their schools. Our city’s schools are failing many, if not most, of our children. They are the most segregated in the nation, funded below court-mandated levels, and are not producing graduates with the skills for today’s job market. However, hardly any parents or students are aware of a valuable resource for them to express their concerns to the Department of Education: Community Education Councils (CECs).

CECs play an important role in our public school system, approving zoning lines, reviewing education programs, prioritizing spending and conducting hearings, among other functions. There is one CEC for every school district, as well as four citywide councils for high schools, special education, English Language Learners, and District 75. Each CEC has 11 voting members, of whom nine are elected by parents. (The one exception is the Citywide Council on High Schools, which has 12 and 10, respectively.) The remaining voting members are appointed by the borough president. Each CEC also has one non-voting member who is a current high school student.

Becoming an elected member of your CEC requires campaigning, somewhat like you would for other elected offices. To qualify to serve on your district CEC, you must be a parent or guardian of a Pre-K, elementary, or middle school student in a non-charter school in the district. For the citywide CECs, you must be a parent or guardian of a student in the respective category.

Learning about the candidates requires proactive involvement on the part of parents, who are often very busy with their everyday lives.

Before mayoral control of the education system, New York City held school board elections, where city residents (parents and non-parents) could run to represent their school district. Information about the candidates was much more obtainable. In fact, it often found you.

Candidates would campaign for these nonpartisan offices in the same fashion as they ran for City Council, State Senate or Congress. The process entailed sending out mailings and letters, handing out campaign literature on street corners, at schools and at subways, sending emails, making phone calls, participating in well-attended and well-publicized forums, and before the days of social media, stuffing way too many flyers under your door. Voters would go to the polls to vote for candidates in the same way they would vote for other representative offices.

CEC elections are much less accessible. Until recently, they were voted on by PTA presidents only, but now all school parents can vote. That said, they must go through a process to do so, which requires registering for a Department of Education account online. This is an account where you can also check your child’s grades, obtain access to their attendance and additional DOE records, and find out about educational forums taking place in their area.

Once parents have signed up, they must then actively seek out information on the candidates. This part of the process disproportionately advantages parents of higher economic status, who often have much more time to explore the candidates, do the necessary research online, attend forums and events, and speak with other parents extensively about the elections.

There are also a myriad of logistical details most parents may not be aware of, including having one vote per each of your children; having a vote in the district where your child’s school is rather than where you live; member resignations being filled by an election at a public meeting rather than the traditional process; and the fact that all candidate forums are required to occur after the candidate application deadline has passed, yet prior to the commencement of the voting period, which must end on May 2 of the election year. There are 11 pages of rules for parents who are either candidates, or voters, or both.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

The fact that all voting is now done online provides an additional impediment to parents who lack sufficient internet access, or who don’t possess the necessary technological equipment or proficiency.

This is why we need more parents to run so that each CEC’s economic diversity reflects that of the district. Without such diversity, whole swaths of a school district may be voiceless. For example, the membership of CEC 2 in my school district includes six parents from the East Side, four from Lower Manhattan, and only one from the West Side. Even then, the only member from the West Side is a parent of a student at P.S. 41, a fine school but also one with a very large endowment, so the less advantaged schools on the West Side have no seat at the table.

Someone may think this configuration is innocuous, but it could present a huge stumbling block to school reforms, such as integration. Imagine if white Upper East Side parents resist any rezoning that may change the racial makeup of their local schools. That is why, if elected to the City Council, I will advocate for reforming the CEC member qualifications so that entire neighborhoods of parents are not left out of decisions on their children’s education.

So, if you have concerns about your child’s future, and can dedicate at least a few evenings each month, why not run for a seat on your CEC? The application to run is available the entire month of February, so the time to act is now!

To learn how to run for your CEC, visit on.nyc.gov/3r1Sg1n. To run or vote in the election, you will also need to create a NYCSA account, available at mystudent.nyc.

Aleta LaFargue is a candidate running for New York City Council in District 3.