‘The proposed Gowanus Neighborhood Rezoning asks a whiter, wealthier community to absorb new growth in order to create new, permanent affordability in a high-opportunity neighborhood with strong transit access.’

Adi Talwar

The view from the 3rd Street bridge over the Gowanus Canal.In the wake of the racial justice uprising after the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, New Yorkers are reckoning with the legacy of systemic racism. A critical area for that reckoning in our city is land use, planning and housing.

Exclusionary zoning, redlining, blockbusting, mortgage discrimination, urban renewal and other policies have denied generations of Black New Yorkers the right to live where they wanted, build intergenerational wealth and security, raise their children in environmentally healthy communities, and send them to school with the resources that would enable them to flourish. Our organizations have delved deep into the impacts across New York City neighborhoods: Fifth Avenue Committee through the Undesign the Redline: Gowanus and ANHD through our Thriving Communities Coalition.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

Over the last decade, the city’s approach to our affordable housing crisis has centered on neighborhood-wide rezonings that rely on the “mandatory inclusionary housing” (MIH) program, which mandates that 20-30 percent of units in buildings built in rezoned areas be below the market rate. Yet so far, all of the neighborhoods that have been rezoned by the city have been low-income and working class communities of color (e.g. East New York, East Harlem, Far Rockaway, Inwood, and Jerome Avenue). The newly constructed units are 70-80 percent market rate units, bringing in new high-income (usually white) residents, with the effect of gentrifying low-income neighborhoods of color. As a result, existing low to moderate income tenants face displacement from rising rents (and even the rents of MIH affordable units are out of reach for many long-time residents).

The proposed Gowanus Neighborhood Rezoning is the first city-sponsored neighborhood rezoning in a whiter, wealthier community. It asks those residents to absorb new growth in order to create new, permanent affordability in a high-opportunity neighborhood with strong transit access. It has far less risk of displacement. In contrast to prior rezonings, it would result in a higher percentage of affordable units in the neighborhood than exists today. For all these reasons, we have engaged in a community planning process for the last several years to try to get this rezoning right.

If we get it right—it’s not there yet—the Gowanus Rezoning holds the potential to move NYC forward on racial equity and fair housing.

A force for fair housing

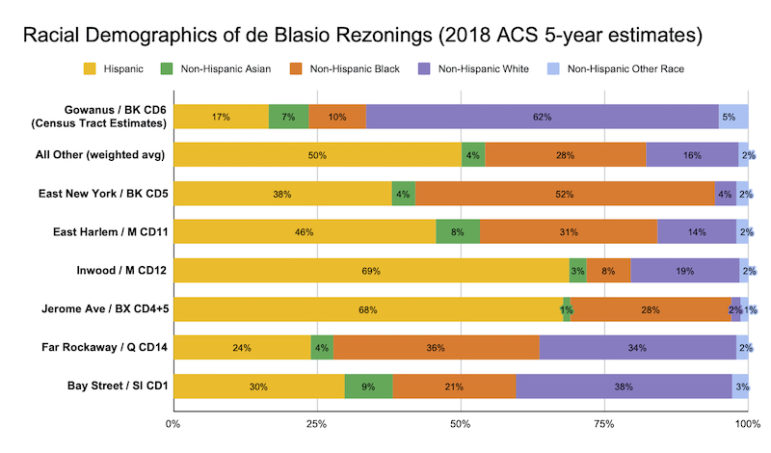

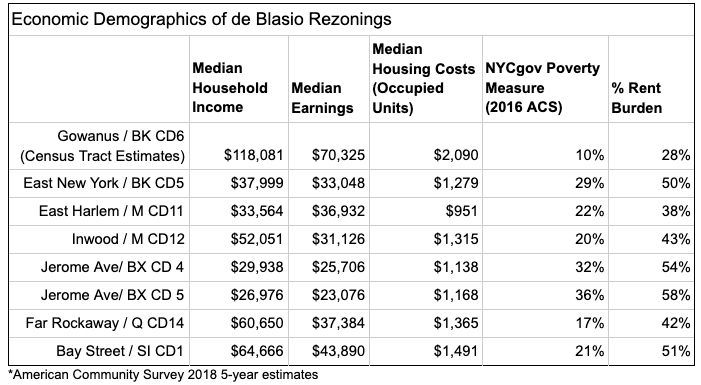

The Gowanus Canal sits in Brooklyn’s Community Board 6, in-between the neighborhoods of Carroll Gardens, Park Slope and Boerum Hill. These neighborhoods are predominantly White neighborhoods with low-rise, homeownership housing. The community district of Gowanus is 65 percent White. This starkly contrasts with previously rezoned neighborhoods, which have been primarily Black and Latino. The community district of East New York is 4 percent White, East Harlem 14 percent, Inwood 19 percent, Far Rockaway area 34 percent, the Jerome Avenue area less than 2 percent. The median household income of those prior rezoning areas ranges from roughly $30,000 to $60,000 per year. In the Gowanus community district, it is $118,081.

Unlike other neighborhoods that have been rezoned, there is far less risk of tenant displacement from the Gowanus Rezoning, because there are very few low-income tenants that remain in privately-owned rental housing (regulated or unregulated) nearby. The poverty rate, adjusted for NYC costs, in prior rezoning districts is over 25 percent. In Community Board 6, it is 9.6 percent and the majority of these low-income families live in NYCHA developments or the permanently affordable housing that FAC owns in the community. The Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development (ANHD)’s Development Alert Project (DAP) Map shows that displacement risk in Gowanus is low. Organizing has made a difference here as well: tenants are better protected because of last year’s changes to the rent stabilization laws, and locally because the city expanded its “Certificate of No Harassment” policy to cover the area.

As a result, the proposed new development under the Gowanus rezoning has significant fair housing potential. Of the 8,200 projected new units, approximately 3,000 (37 percent) will be affordable (2,000 through MIH, and 950 on the city-owned Public Place site).

Rather than fuel displacement and gentrification in a low income, working class neighborhood, the rezoning would be a force for racial and economic integration in a wealthy, white one. That’s the opposite of gentrification.

And it would happen in a neighborhood that has already begun taking concrete action to integrate its public schools. District 15 recently adopted a middle-school admissions plan that eliminates screens and ensures access to school seats for low-income students, with very promising initial results. Conversations are underway to extend that work to the neighborhood’s elementary schools.

Improvements needed

That’s not to say the Gowanus Rezoning as currently proposed would adequately achieve racial equity or environmental justice. For over five years, members of Gowanus Neighborhood Coalition for Justice (GNCJ) have been working together to demand a Gowanus rezoning based on principles of social, economic, environmental, and racial justice — and that work continues.

First and foremost, there must be funding and an implementation plan with significant resident input to address critical unmet capital needs at NYCHA’s Wyckoff Gardens and Gowanus Houses, where residents have experienced years of unhealthy, unsafe, deteriorating living conditions. The city must take responsibility for years of neglect and secure the resources needed to improve conditions and reopen their community centers.

In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, the city’s plan must be improved in other ways as well. An Environmental Justice Special District must insure “Net Zero CSO” (combined sewer overflow) in the Gowanus Canal, advance equity, and include ongoing local input. An emergency preparedness plan needs to be in place for future crises. More support is needed for small businesses devastated by the COVID crisis and for new low-income small business entrepreneurs. Gowanus Green should provide 100 percent permanently affordable housing.

And an equitable rezoning can only come from an inclusive process: the community must have a real voice in the next steps of the Gowanus planning process. Social distancing guidelines will make it more difficult for effective and inclusive community involvement in the ULURP process. If comments and testimony are expected to be made online, access to technology must be made available, particularly for public housing residents. And we should consider new approaches, including open-air conversation as weather allows.

Why we shouldn’t wait

Some people have recently suggested that the Gowanus Rezoning should wait: Until there is a vaccine. Until there is a new mayor. Until the city adopts new and different policies for environmental review. Until a new law is passed and implemented requiring racial impact analyses.

Some of the people calling for these measures don’t want new affordable housing in the area at all. A new proposal calls to create a public park on the one city-owned site slated to be 80-100 percent affordable housing, with a park along the canal, and a new, integrated public school. A park alone is a lovely amenity for the existing residents who already live in the area, but where is the racial impact analysis of cancelling the affordable housing and the school?

To be clear, we support the call for racial impact analyses of land use and other city policies. We have long supported even deeper structural changes to New York City’s land use policies, including comprehensive land-use planning, with deep community engagement, and with fair housing, equity, and integration as goals, rather than making land use decisions solely in response to developers’ applications.

But that doesn’t mean we should delay the Gowanus rezoning—it means we should make sure it’s a model, and a step forward, for the kind of fairer, more equitable planning we are demanding. We are asking the Department of City Planning to release the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) data for the Gowanus rezoning early, before the ULURP process begins, so we can have a more informed conversation.

Because because of its unique position as the one potentially “fair housing” rezoning of this administration, and because of the long-standing community organizing that has taken place, the Gowanus rezoning—especially with the added investments, accountability and protections that GNCJ has called for—has a lot to offer the city more broadly in thinking about what such processes would look like.

So let’s recognize calls to “wait” for what they too often are: an effort—whether intentional or not—to delay steps forward towards environmental, social, and racial justice in NYC.

Michelle de la Uz is the executive director of the Fifth Avenue Committee. Brad Lander is a City Council Member representing Brooklyn’s 39th District (including Carroll Gardens, Park Slope, and Gowanus). Barika Williams is executive director of the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development.

Editor’s note: At the authors’ suggestion, the demographic numbers for Gowanus have been slightly adjusted from an earlier version to better reflect Brooklyn CB6 using census tract boundaries.

14 thoughts on “Opinion: How the Gowanus Rezoning Could Push NYC Forward on Racial Equity”

Ok. Now Thank you City Limits for doing this. How about these same specifics for the Flatbush, East Flatbush, Bed-Stuy and Brownsville neighborhoods. Its happening there too.

Because of CM Lander’s anti-police – pro-criminal law enforcement policy – this will rezoning will mean nothing as the neighborhoods will be abandon because criminals will rule

Has City Limits posted an article written by a Gowanus activist to show the issues from their point of view? If so, I missed it. The road to the Gowanus rezoning has been a farce (asking locals to put slips of paper of their preferences for rezoning into fish bowls, a representative shouting down locals at meetings – please). The locals are not fooled (and we’ve all “seen this movie before”). Also, keep in mind “some folks” have future political ambitions that they likely will need funded by the real estate developers who are salivating over these rezonings.

P.S. If NYC was creating so many “affordable” new units (and we both know the new units are not “affordable”), the city wouldn’t have lost so many of its artists to other cities (who could no longer afford to live or work in NYC). I personally know quite a few artists who left for Philly, Detroit, Asheville and other places over the past number of years. No one wants to live in a sterile/boring NYC filled with bankers, real estate developers and/or uber-rich people.

So sorry you missed these:

https://citylimits.org/2020/07/15/opinion-gowanus-rezoning-must-heed-covid-19-lessons-offer-racial-justice/

https://citylimits.org/2020/08/03/opinion-fairness-requires-that-nyc-pause-the-gowanus-rezoning/

Why are we building Apartments for low income people on a polluted brownfield site?

A better use would be a park

Plus the city gives enormous tax breaks to big developers and sticks it to small homeowners

It’s cleaned up, and they’re building apartments because NY has a shortage of hundreds of thousands of units.

Huh? That’s The pre-pandemic reality, not the actual reality of now. https://therealdeal.com/2020/09/28/from-unthinkable-to-reality-cheap-nyc-apartments-sit-vacant/amp/

I am sorry, City Council member Lander, but housing low and moderate income people on an EPA certified brownfield site with toxic plumes extending for hundreds of feet underground, is just another form of racism and inequity. My understanding is that it has been called “the worst coal tar site in the State of New York.”

National Grid’s remediation of the toxic site will only go down 2 feet. A 30 story building will need to be footed, therefore, in toxic waste. Would council member Lander live in the buildings or let his children or family do so?

Everyone wants affordable housing. Gowanus is 65% white. Diversity is the engine of this city. It’s a more complicated argument and process than is being portrayed here. Just calling it NIMBY is a shallow argument.

Environmental justice, like all other forms of justice, is part of a necessary dialogue. Nothing should be rushed. These are questions that require a deliberative and transparent process.

It’s been in the works for a decade. Nothing has been rushed.

The original proposal 30 years ago, by the Gowanus Community Redevelopment Corporation was for a public park. I read it. What happened to that proposal?

It is important to pay attention to who wrote this article: they are all people who have strong ties to the developers of properties in Gowanus. The writers of this article will directly benefit from the proposed development. Do not be fooled, the Gowanus rezoning has no protections or accountability to NYC residents, only to developers.

Michelle de la Uz sits on the City Planning Commission. Yes, she will have to recuse herself when it comes time for the CPC to vote on Gowanus rezoning. But meanwile, she is publicly advocating and pressuring for Gowanus Rezoning in her position as Director of the Fifth Ave. Committee that stands to benefit financially from the proposed Gowanus rezoning. How is that NOT a conflict of interest?

Only 2 feet of coal tar now being removed from Public Place, not the original 8 feet. Sewage overflow tank construction delayed again. Public land gifted to Hudson Properties and $130,000.00 gifted to Brad Lander by real estate interests in 2017. Smells worse than the Gowanus Canal.

Wow, what a flip, from developer led development to now 100% affordable. It would be believable if there were teeth to it. This project has been developer led until there was pushback from many groups lifting up their voices. To suggest that their wanting delays until a sincere environmental review is done BECAUSE they don’t want affordable housing in their neighborhood is manipulative. Mr. Lander, you have been pushed to make the development 100% affordable. Now you should be pushed to ensure that building in a flood plain does not harm the working class people who live in 3 story houses.

If you cared about working class people you would insist on a true environmental review and then the city would dictate to developers what is safe to build.

So, yes, the rezoning should absolutely wait until an environmental review of its impact is done. This is how communities are protected in the future. Shame on you for acting as if this has been motivated by affordable housing from the beginning. It has been motivated by a desire for political positioning.