Marlene Peralta

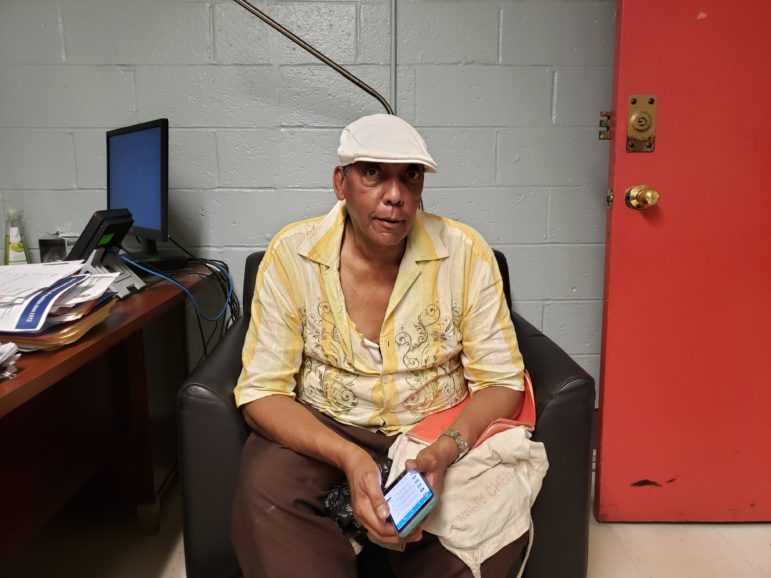

Elio Cuni, a 67-year-old Cuban immigrant who is at risk of being evicted from his rent-regulated one-bedroom apartment in Harlem.

This article was translated from Spanish.

Please read our Editor’s Note.

Este artículo fue traducido del español.

Lea la versión en español aquí.

New York is growing old quickly. The city’s over-65 population tripled between 2005 and 2015, and for the first time it surpasses the one-million mark.

“Our report found that immigrants are almost half of all elderly New Yorkers in the city and that they are practically driving the population growth among older people in the city,” said Christian González-Rivera, researcher for the Center for an Urban Future and the main author of a number of reports, including one entitled “New York’s Older Adult Population Is Booming Statewide.”

And that is not all: “This is only the second time since World War II when 50 percent of the city’s elderly population is immigrant. Back then, almost all of our elderly had come from Europe, including a large number of Jewish people,” said the expert. According to data collected by the City 1.4 percent of all seniors are undocumented.

By the year 2020, immigrants will form the majority of the elderly population in New York City, with Dominicans, Mexicans and Chinese as the fastest-growing groups, said González-Rivera.

Growing old in New York – an expensive and hard to navigate city – poses several challenges to people unable to work due to health reasons or who have mobility problems, among other age-related ailments. Many seniors lack sufficient income or a family to offer support.

For immigrant Latinos, the challenges are even greater, as this group is generally the oldest, poorest and least eligible for assistance, particularly if they are undocumented. The report released by the Center for an Urban Future states that elderly immigrants are 50 percent more likely to live in poverty. For their part, seniors born in the U.S. and Puerto Rico have a high probability of living in extreme poverty, according to data from the City’s Department for the Aging (DFTA.)

Like the general elderly population, many Latino U.S. citizens and legal residents depend on Social Security benefits that, on average, barely reach around $1,400 per month, according to the Social Security Administration’s latest statistics.

On the other hand, it is worth noting that undocumented immigrants are not eligible for federal assistance programs such as food stamps, housing vouchers, or public housing. Meals on Wheels, the home delivery service for elderly people, does serve people regardless of immigration status because it is municipally funded.*

Navigating challenges and resources as a senior

“Our centers serve mainly women from a generation in which women did not have jobs, and that is the reality for most of the seniors, regardless of their ethnic group,” said former councilwoman María del Carmen Arroyo, who now manages the ACACIA senior centers. The social services organization was founded by Puerto Ricans over 40 years ago. Many people turn to ACACIA centers to obtain free lunches, for their health programs and for their Zumba, salsa and tai chi classes.

Every individual interviewed by City Limits said that affordable housing is the most urgent problem facing immigrant seniors—not unlike the rest of the city’s population—ffollowed by access to transportation and medical care.

At ACACIA’s Carver Senior Center in East Harlem, one of more than 200 centers funded by the DFTA, we found Elio Cuni, a 67-year-old Cuban immigrant who is at risk of being evicted from his rent-regulated one-bedroom apartment in Harlem. He will have to appear in court next month because his landlord is accusing him of not paying his rent.

Cuni said that, a few months ago, the building’s management offered him money to vacate the apartment. This is one of the most common tactics used by landlords in working-class or gentrifying neighborhoods, who later rent the units at much higher prices. Cuni said that he is only one of two Hispanics living in the building and paying a low rent.

“My mistake was that I accepted and fell in their trap,” he said, showing text messages in which someone offered him $7,000. Cuni accepted, citing the precarious living conditions he endures, but later changed his mind.

The tenant only pays $623 per month, but he says that his apartment has been mice-infested for a long time. “Do you know what it’s like to try to sleep and feel these animals tickling your body in the middle of the night?”, he said. “In all the years I have lived there, I had never complained. I do all the repairs and painting myself because I do small construction work. Last year, I was freezing all the time while they were supposedly fixing the heater.”

Carver Senior Center Director María Rivera begged him not to make that mistake.

“He walked in here very frustrated and, when he told me what he planned to do, I called a number of people to ask for advice. I told him not to do it, not to accept any money and not to sign anything,” she said. Cuni had found it difficult to pay his rent for two months due to late Social Security checks of around $500. His landlord is now using this as his argument in housing court to evict Cuni from the apartment where he has lived since 1988.

Social worker Debbie López, clinical supervisor at JASA in The Bronx, said that she sees similar cases.

JASA, formerly known as the Jewish Association Serving the Aging, was founded over 50 years ago. At its 22 senior centers in The Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens, the organization has seen the way the older population has changed in the last few years. Many of their customers today come from countries such as Ecuador, Honduras and the Dominican Republic, to name a few.

“I had never worked with such a large destitute population in mental health programs,” she said. “I currently have a 79-year-old woman living in a shelter, and it is devastating.”

In 2017, the number of homeless people over 65 doubled to over 2,000, while the rate of empty apartments paying $800 or less was just 1.1 percent.

The problem is that there are not enough affordable housing units for everyone. Thousands of people are on waitlists for new constructions. In addition, López said that housing vouchers issued to help seniors pay their rent are not accepted everywhere. Undocumented people, for their part, do not even qualify for these subsidies.

López explained that the geriatric program she manages was created 3 years ago precisely to serve the Latino population in The Bronx. Funding was provided by Thrive NYC, the initiative led by the City’s First Lady Chirlane McCray to expand access to mental health services.

The social worker added that some seniors arrive in need of legal aid to solve their immigration status, while others say they cannot access the programs the centers offer for lack of money to pay for transportation.

Mayor’s office responds

According to researcher González-Rivera of the Center for an Urban Future, “Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has invested a great deal of money on the Department for the Aging, reverting former Mayor Bloomberg’s policies withdrawing funding. Still, the City is only financing programs that already existed. No innovations have been made despite the changes and increase we have seen in the senior population.” In other words, budgets have not adapted to reflect the growth of this demographic.

In New York, services offered by hospitals and senior centers funded by the city or with DFTA contracts are available to any New Yorker regardless of immigration status. In fact, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced recently that he would extend coverage to New Yorkers with no access to health insurance or who do not qualify for Medicaid, including undocumented immigrants. The Thrive NYC program has also expanded to offer mental health services to everyone, no matter their immigration situation.

Regarding the affordable housing crisis, a spokesperson for the City’s Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) said in a statement: “Guaranteeing that New York City seniors will have access to housing they can afford is a priority and, under this administration, we have created more than 7,700 affordable housing units for seniors. We also provide an array of resources in several languages so that New Yorkers of any social condition can receive the help they need to live in safe and affordable homes.”

The new DFTA commissioner

Many are hopeful about the work new DFTA Commissioner Lorraine Cortés-Vázquez, of Puerto Rican descent, will carry out. The experienced public servant was appointed to the position by Mayor de Blasio only two months ago. In addition to other high-profile positions, Cortés-Vázquez was Secretary of State under the administrations of Governors David Paterson and Eliot Spitzer.

“All my life I have been committed to diversity and inclusion, and that is not going to change at the Department for the Aging,” said Cortés-Vázquez in an interview with City Limits. She also said to be aware of the senior community’s complaints, adding that they are extremely effective when expressed in annual public hearings and other events the DFTA holds throughout the year.

Complaints citing inequality in the way senior centers are funded have also emerged recently.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

“One of the things we will bring back is the RFP (request for proposals) procedure to ensure that every community has equal chance to apply to the resources they need. It will be the first time in many years that we will make use of this process,” said Cortés-Vásquez.

About the risk of evictions and the lack of affordable housing, she said: “One thing that has worked very well and that I am committed to continue is [offering] legal representation against landlords to prevent seniors from being evicted. This is one of the things I want to keep doing. If we can keep seniors in their homes, that is a very significant step.”

(Translated by Carlos Rodriguez.)

* This paragraph was corrected to report that Meals of Wheels does serve the undocumented.

3 thoughts on “What Aging Means for Immigrant New Yorkers”

Why should landlords me charity cases. The city needs to pay up if they want an aging population that cant support their self to stay in an expensive city

Debbie —

the City does pay up through programs such as the Senior Citizen Rent Increase Exemption (SCRIE) which provides landlords with a penny for penny tax credit. When a senior (with income of $50,000 or less per household and the rent is 1/3 the household income or more) enters the program his rent is “frozen” at the level it is at that moment — as the rent continues to rise yearly the tenant pays his share of the rent and the landlord gets a tax credit for what the tenant does not pay.

In most cases this stabilizes the situation so that seniors can remain in their apartment. But in cases where a tenant’s rent on being forced to stop working is higher than 1/3 their income — and at my agency we regularly see seniors whose rent are 50% or more of their income — the program is not sufficient . And while their is a process where you can appeal to have the tenant’s share lowered – it is time consuming leaving the tenant open to eviction while the process is in motion.

And in cases like Mr. Cuni’s where he was tricked into accepting a settlement well below the norm — it can’t help at all — only a lawyer can.

Good afternoon, am just trying to assist an elderly gentlemen over 65 years of age frail, unable to ambulate without a walker, chronic medical ailments and no relatives to assist him at this moment. The gentlemen is an ineligible alien and in great need of some type of assistant living. If you can directed me to any agency or program that can assist him to live a half decent life; verses being in the street or shelter it would be greatly appreciated.