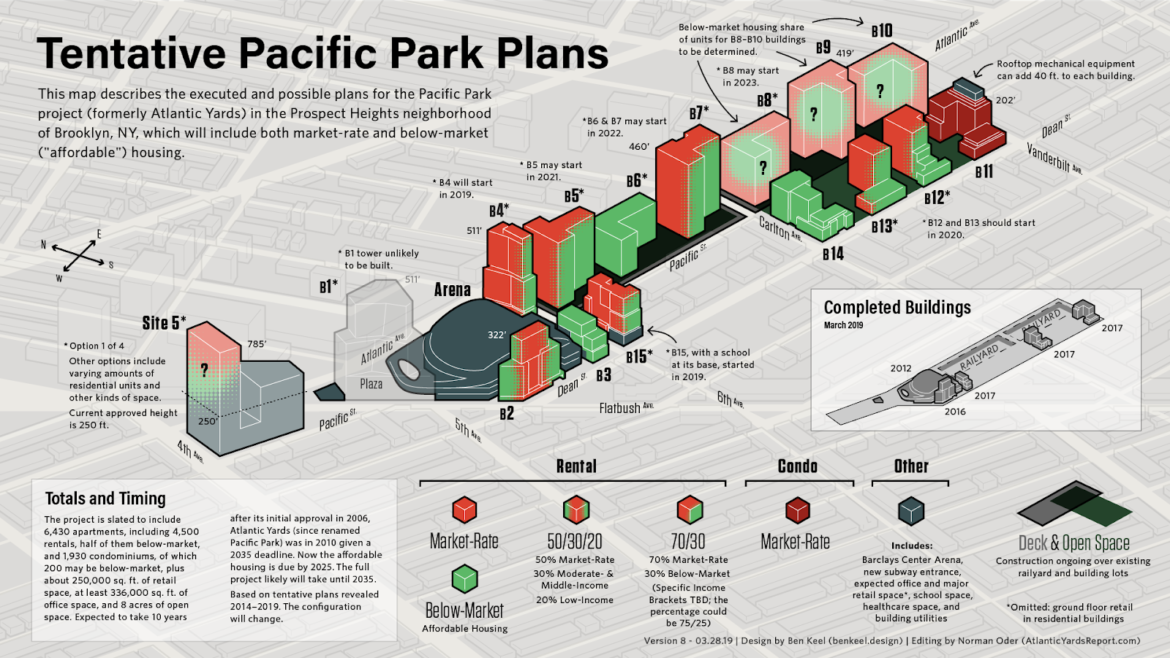

Map by Ben Keel and Norman Oder. Click here for a larger version.

A looming affordable housing deadline in Brooklyn may be met—but only because state requirements are far looser than what Brooklynites were promised regarding the project launched in 2003 as Atlantic Yards.

A newly acquired document discloses a plan, otherwise kept under wraps, for the developer of the vexed project, called Pacific Park since 2014, to meet an ever-closer deadline: building the required 2,250 affordable housing units by May 31, 2025.

Only 782 affordable units have been built, in three of four completed towers, and housing advocates have raised questions about the developer’s capacity to meet that deadline. After all, recently announced plans to start four more towers this year and next would deliver only about 60 percent of the required total.

The solution–to build three additional towers, including an “100 percent affordable” rental building, likely with 450-plus units—has not been described publicly by developer Greenland Forest City Partners nor Empire State Development, the state authority overseeing the project. They’ve both resisted explaining how the 2,250 total would be reached, despite requests from some members of a new body aimed to increase project transparency.

The new details about Greenland Forest City’s plan were made available not in Brooklyn but half a world away in China, as part of a document discussing unbuilt project sites, treated as collateral for immigrant investors seeking green cards under the federal government’s EB-5 program.

Asked by City Limits to confirm or clarify the plans—the document was prepared for a lender to the developer, not the developer itself–the developer instead offered a general statement: “Greenland Forest City Partners is fully committed to meeting our target of 2,250 units of affordable housing by 2025, and our development plan for the remaining affordable units will be in full compliance with the outlined General Project Plan.”

Why the unwillingness to say more?

Perhaps because the company’s previous “100 percent affordable” buildings have faced criticism, given they’ve been skewed to middle-income households earning six figures, with such units tough to rent, as City Limits reported .

The affordability of that future “100 percent affordable” tower remains unspecified, but even middle-income apartments could help the developer avoid monthly $2,000 fines for each missing unit. Despite earlier promises to serve a wide range of incomes, the project’s Development Agreement does not require specific levels of affordability, thus allowing a middle-income skew.

The lack of candor might be because the document indicates that at least two, and possibly three, of the project’s remaining towers won’t be built by 2025. Though that year was previously said to mark full completion of all 6,430 apartments, both affordable and market-rate, ongoing delays have raised doubts, given the need to build a costly platform spanning two blocks of the Vanderbilt Yard, under which Long Island Rail Road trains are stored and serviced.

If so, that would further delay the much-hyped open space at the project’s eastern end, the main segment of the “park” for which the complex is now named.

It’s another reminder that public promises can be attenuated when developers and government entities finally sign contracts. This issue was raised in the debate about Amazon’s proposed Long Island City campus, subject to a nonbinding Memorandum of Understanding later to be memorialized in contracts. A delayed public promise was recently highlighted regarding the 300 Ashland tower near the Brooklyn Academy of Music; as the Brooklyn Paper recently reported, four cultural spaces—including a museum and library—have yet to arrive, while an Apple Store and Whole Foods Market 365 have already opened.

A shifting timetable

Atlantic Yards faced both delays and a shifting timetable. When launched by Brooklyn-based Forest City Ratner, the project, with an arena and 16 towers over 22 acres, was supposed to take 10 years to build.

That same aspirational 10-year timetable was professed when the project was approved in 2006 and, after litigation and the recession caused delays, re-approved in 2009.

But two contracts offered wiggle room. A deal for development rights over the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Vanderbilt Yard, which occupies about 8.5 acres of the site, was revised to allow payments over time, until June 1, 2030 , with the last of 15 annual payments of $11 million due then. Moreover, a Development Agreement signed with Empire State Development gave the developer 25 years, until 2035, to finish the project.

In 2014, as Forest City prepared to sell 70 percent of the project (excluding one tower, and the Barclays Center operating company) to Greenland USA, the arm of Shanghai-based Greenland Group, some Brooklyn activists threatened a lawsuit on fair housing grounds, saying the delayed buildout harmed black residents threatened by steady displacement, rendering them ineligible for community preference in housing lotteries.

Averting a lawsuit, and easing the Greenland deal, an agreement revealed that June in a prominent New York Times article set a new 2025 deadline for the income-linked housing, with two “100 percent affordable” rental buildings to start in 2014 and 2015. The developer at the time contemplated numerous fully market-rate buildings, both condos and rentals, a departure—as City Limits reported—from the original agreement negotiated by New York ACORN to build all rental buildings as 50 percent affordable.

(This income-mixing had been hailed as one of the hallmarks of the Atlantic Yards deal: Bertha Lewis, then executive director of New York ACORN, Forest City’s housing partner, in a 2006 City Limits essay touted a new model, in which “the affordable units [would] be spread throughout every rental building at random on every floor.”)

In 2017, when those “100 percent affordable” buildings opened, not only did the city’s housing lottery deliver few takers for middle-income units, as City Limits reported. Greenland Forest City also began offering a free extra month on a one-year lease, borrowing an incentive typical for market-rate units, and later offered two and even three months gratis.

Prediction from 2014: completion by 2025

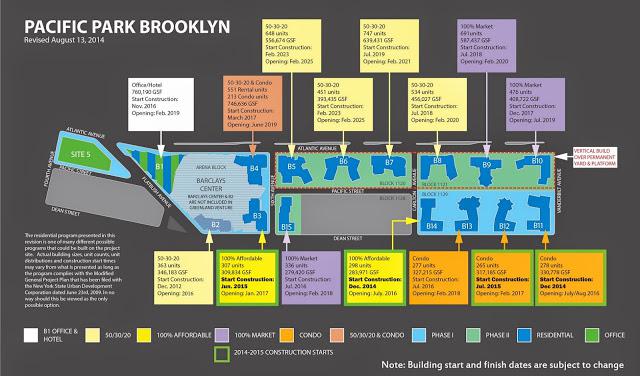

When would Pacific Park be finished? A map (below) charting the tentative buildout, prepared by Greenland Forest City in August 2014, predicted completion by 2025, with the final three buildings delivering major portions of affordable housing: all three, built over that platform, would have a 50/30/20 configuration, with 20 percent low-income units, 30 percent moderate- or middle-income, and the remaining 50 percent market rate.

August 2014 map prepared and distributed by Greenland Forest City Partners

However, that plan was upended by delays, with no new buildings starting after mid-2015. In November 2016, in a sign of tension within the joint venture, Forest City unilaterally announced a pause in construction, citing a glut of market-rate buildings in and around Downtown Brooklyn, rising construction costs, and uncertainty about the 421-a tax break.

Though a spokeswoman claimed the joint venture was “fully committed” to its obligations, completion of the full project by 2025 seemed doubtful. Forest City’s financial model “extends to 2035,” an executive at parent Forest City Realty Trust said. That suggested the project might be finished, if not that year, not long beforehand.

Presaging an end to the stalemate, in early 2018 Greenland bought all but 5 percent of the project from Forest City. Later in the year, Greenland announced it would lease three parcels to two other established local developers: The Brodsky Organization and TF Cornerstone, adding momentum to the buildout.

Moving forward, but how fast?

Two towers should start this year, built by Brodsky and by Greenland, with 30 percent affordable housing, while TF Cornerstone plans to build two towers next year, with 25 percent or 30 percent affordability. Those examples conform to the options under the revamped 421-a program, known as Affordable New York.

However, those four buildings—all on terra firma, not over the railyard–might deliver enough below-market units to reach a total of 1,334. If so, a gap of 916 units to reach the 2,250 requirement by 2025 would persist.

That deadline has been on the minds of housing advocates. At a January 2018 meeting of the Atlantic Yards Community Development Corporation (AY CDC), a state advisory body set up as part of that 2014 settlement, board member Barika Williams, then of the Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development, asked if Greenland could update that 2014 map.

“It’ll probably be sometime later this year,” said Greenland USA executive Scott Solish.

That didn’t happen, and Williams has left the board. Later last year, however, Greenland Forest City quietly updated a disclosure to condominium buyers, stating that “the remaining buildings, and the balance of the public park, [are] projected to be completed in phases by 2035.” The previous disclosure had said 2025.

“A full Pacific Park completion by 2035 reflects the buildout horizon allowed by the general plan,” a spokesperson for the developer said at the time. “Our affordable housing commitments will be met by 2025.”

Still, that earlier deadline and the affordability configuration delivered so far depart from the initial timetable and promise, which were key to gaining political support for the project. Atlantic Yards was promoted, in a Community Benefits Agreement said to guarantee such things as affordable housing and job training, as encouraging “systemic changes in the traditional ways of doing business on large urban development projects.”

The delays, coupled with ever-rising base income levels for affordable units, make the project less likely to serve those lower-income New Yorkers, many associated with ACORN, who marched in support, and less likely to stem gentrification.

Pressing for details, unsuccessfully

Questions about the timetable have persisted. More recently, at a March 15 meeting of the AY CDC, board member Gib Veconi, a Prospect Heights activist who’d helped negotiate that 2014 settlement, proposed a resolution requesting an updated timetable, noting that a 25 percent affordability level spread throughout the remaining buildings wouldn’t meet the 2,250 goal.

Veconi’s motion met resistance from AY CDC President Marion Phillips III, an executive for parent Empire State Development. “Greenland’s not required to give us a projection, and I’m not trying to put them in a position so that we can play gotcha,” he said. “They have a responsibility, and we plan to hold them to a responsibility, for 2,250 units.”

The vote on the motion failed narrowly, despite the AY CDC’s charge to be “monitoring developer compliance with all public commitments.”

Greenland’s Solish did say his company had general plans for three of six projected buildings over the railyard, coming after the four towers expected to start this year and next. Greenland Forest City is already designing B5, across from the Barclays Center, he said, and is beginning to design adjacent B6 and B7. The three would cover one of two blocks requiring a platform.

However, Solish offered no details about affordability, which instead was revealed in the document this journalist acquired: B5 and B7 would contain 30 percent affordable units, sandwiched around B6, with 100 percent affordable units. All were said to start by 2021 or 2022, though, given the development’s history, those projections may be aspirational.

When built, those towers could supply enough units to approach the 2,250 total by 2025. Given previous estimated unit counts, B5 and B7 would generate 1395 apartments, 418 of them affordable, while B6 would add 451 affordable units.

That 869 total falls short of the 916-unit gap projected above, but might be adjusted, thanks to more smaller apartments, and/or some shifts in bulk. Also, according to the document, another building over the railyard, B8, was projected to start in 2023, with affordability unclear—though that seems an aggressive pace. Or, perhaps, the long-gestating plan (as reported in City Limits in July 2016) for two towers at Site 5, catercorner to the Barclays Center, might include some affordable units.

Whatever the result, it’s likely the required affordable units will arrive before all 4,180 market-rate units. To get subsidies, the developer might have include affordable units in all towers. If so, the project, once completed years behind the initial schedule, might ultimately contain more affordable units than promised, albeit many of them at higher rent levels.

How affordable?

One lingering question regards the levels of affordability. Buildings with 30 percent affordability would take part in the revamped 421-a plan, known as Affordable New York: Options under current subsidy programs would include a significant amount of middle-income units, meaning above 120 percent of Area Median Income (AMI):

• 30 percent affordable: at least 10 percent at up to 70 percent of AMI (currently $65,730 for a three-person household) and 20 percent at up to 130 percent of AMI ($122,070 for a three-person household)

• at least 30 percent affordable at up to 130 percent of AMI

So, one option lacks any low-income units and, at most, one-third of those new affordable units would be for low-income households. This would depart from the initial Forest City-ACORN agreement: that 40 percent of the affordable units would be low-income, with a lower income ceiling, up to 50 percent of AMI. It also eliminates a moderate-income category, as well as a category of even higher middle-income households, with income up to 160 percent of AMI.

At a public meeting in January, an ESD representative stressed that the developer was required to deliver 2,250 units, but not at specific rent levels. (The previous “100 percent affordable” buildings included units for households earning up to 165 percent of AMI, with two-bedroom units renting for $3,206 and $3,223.)

“It’s a goal to try and maximize and diversify the affordable [housing] to the greatest extent possible,” Greenland’s Solish commented. “A lot of that depends on city, state, and federal subsidies that may or may not be available.”

“Would it be fair to say that the affordability levels that were stated in the [Forest City-ACORN agreement] are right now kind of looked at on a best-efforts basis by the folks that are going be doing the development?” Veconi asked.

“It’s our hope that we’re going to be able to achieve them,” Solish replied.

2 thoughts on “Ever-Shifting Pacific Park Plan Highlights Uncertainty of Big Development Schemes”

and they will leave out the 20,30,70,75 and 80 AMI always you will see only 40,60, 130 and up AMI, uneven and unjust, we all need affordable housing /income base

I would.like an opportunity to obtain an apartment here, but “affordable” on my income of 45,900 isn’t 2000 dollars a month