Dorian Block

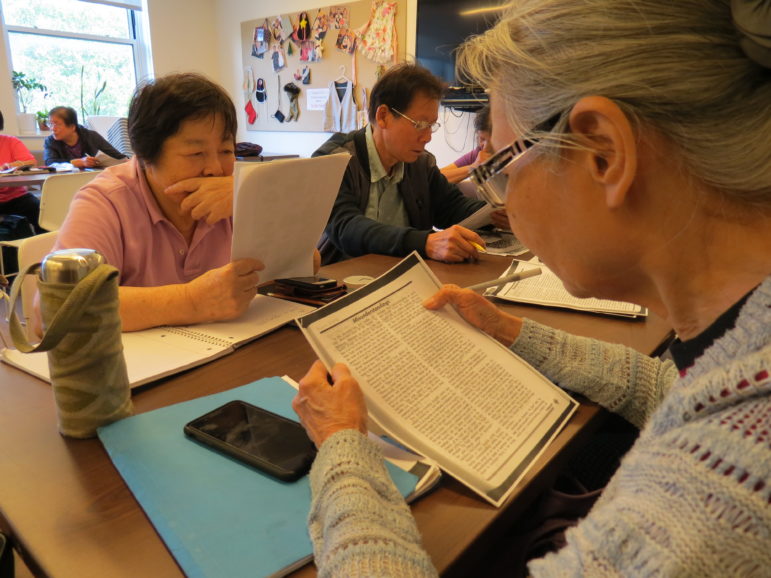

At the Manny Cantor Center on the Lower East Side on a recent Thursday. Twenty people come from all boroughs of the city traveling by subway and bus, to one of the few places that has an evidence-based intensive English class for older New Yorkers.

New York City is aging, fast–a demographic fact creating huge opportunities and challenges for residents old and young. Read City Limits’ ongoing coverage of older New York and the issues it’s facing here.

Yumei Wang, 79, has a modest dream. She would, for the first time in her adult life, like to open her mail and understand what the words on the paper mean.

Wang came to New York from China when she was 18 years old and worked as a nanny for many years. She relied on her husband’s English, and then later her son’s, otherwise staying in Chinatown herself. Wang’s son is now grown and lives independently, and her husband died last year. On top of Wang’s grief are piles of worry about accomplishing daily tasks like writing her rent check and paying her cable bill without understanding them or knowing how to write in English.

Similarly, Eliena Wong, 72, has a basic hope. Wong wants to be able to call the police or to ask for help in an emergency.

“I go outside and take the subway. I feel so nervous,” Wong says. “If I make a mistake and something broken (in the subway), I need to get home. If something is wrong, how can I call someone to help me? I do not understand.”

There are 1.6 million people over age 60 in New York City, which is about 19 percent of the city’s overall population (or the size of the entire population of Philadelphia). Demographers expect that New York’s population 60+ will have increased by almost 50 percent between 2000 to 2040.

By and large, these older New Yorkers are immigrants. The growth in New York’s older immigrant population has far outpaced that of the U.S.-born senior population. According to the U.S. Census, while the number of native-born seniors in New York grew just 6 percent from 2010 to 2015, the number of immigrant seniors jumped 21 percent.

While many older immigrants have lived, worked and been a part of communities in New York for most of their adult lives, many have never learned English. Others have come to New York recently, usually to join children and grandchildren.

According to the Center for an Urban Future, 59 percent of older immigrants in New York speak English less than very well. And 36 percent of older immigrants live in what is called “linguistically isolated households,” meaning that nobody in a given household over the age of 14 speaks English.

City Limits is a non-profit.

Members make us go.

Become one today

The ramifications of having several hundred thousand older people who are unable to communicate in English – to understand our city’s systems or contribute the way that they would like – has tremendous implications for the city’s economy, its healthcare systems and for the children and grandchildren these older New Yorkers have and are still raising. Studies conducted over the last decade also show that literacy affects how long people live.

Yet, the prevailing presumption amongst policymakers at the national level, and those who focus on literacy and adult education in the city, is that older people are not a priority for adult education.

“There is a myth we have that older people don’t want to learn if they haven’t learned English already. If they lived here long enough, they don’t want to learn or cannot learn,” says Karen Taylor, Director of the Weinberg Center for Balanced Living at the Manny Cantor Center on the Lower East Side, which offers one of the city’s only English as a Second Language classes for older adults.

The research on older adult language learning is thin, but studies do show that while people’s speed of cognitive functioning slows as they age, there is still a great capacity to learn new skills and languages. One recent study suggests that older adults can reach high levels of new-language acquisition if they are just given more time than those who are younger.

In the U.S. overall, despite the fact that many retirees have more time for learning, just 3.6 percent of adult education participants are 60+, according to the Office of Vocational and Adult Education’s National Reporting System.

This is largely because government funding for adult education has increasingly prioritized workforce outcomes which are tracked based on people’s Social Security numbers and the employment and wage gains they achieve. The 2014 Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, the largest provider of funding for English and literacy classes, prioritizes students earning high school equivalency and college degrees. Providers vying for funding seek out students with the potential to get their degrees or go to work, and they avoid enrolling others.

John Hunt is executive director for Adult Continuing Education at LaGuardia Community College, where they have 500 students a semester taking English classes, and where there are hundreds of people on the waitlist at any given time.

“When we switched over to this new Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, we are asking (potential students) for wage gains and employment status, and being unavailable for a job is not a valid status,” Hunt says. “Programs choose not to enroll seniors because they aren’t going to get job entry gains, wage gains. It won’t help us.”

Hunt says that his programs reach out to potential students on the waiting list who plan to work, but older adults are not called back. “If seniors come because they are isolated and we turn them away, I don’t know what happens to them,” Hunt says. (In a statement provided to City Limits, LaGuardia Community College said, “All wait-listed English language learner applicants for LaGuardia Community College’s ESOL classes are invited to orientation sessions, regardless of age or employment status, and many students of all ages with civic and family engagement goals are currently enrolled in Fall classes.”)

Similarly, Michael Hunter, the program director for Adult Literacy at University Settlement, which serves 1,000 adults a year in literacy and English classes, says that there are very few spots available for the general population, or those who will not have clear workforce outcomes or children or grandchildren whom they are raising.

“I think that if I compare it to how we think of children, we don’t value adults, let alone seniors,” he says.

For the past few years, Mayor de Blasio has excluded the $12 million in city funds spent on adult education from his proposed budget. The adult education community, led by the New York City Literacy Coalition, a coalition of about 50 member organizations, responds with thousand-person marches, and the money has routinely been reinstated.

Service providers like Hunt and Hunter are left vying for federal, state and local money annually and having to impress with numbers that show the educational degrees their students have earned, that they are newly employed or making more money.

This change in funding has also led to more time-intensive classes for fewer students. In 2014, in New York State, 102,784 people participated in adult education, as compared to 176,239 in 2000, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. In New York City, there are about 60,000 students taking English and literacy classes, said Kevin Douglas, Co-director of Policy and Advocacy at United Neighborhood Houses and head of the New York City Literacy Coalition.

And at the macro level, while Taiwan and the European Union have established strategies and goals for lifelong learning, the U.S. has not. According to an annual report the U.S. submits to UNESCO, an agency of the United Nations that promotes education for all, older adults are not one of the country’s target groups for adult education.

Also relevant is a report put out by the U.S. Department of Education this year on digital literacy or people’s comfort using technology, another critical skill. The study only measures people up to age 65, despite older people being the least adept at technology. “Older adults” are referred to in the report, but they are those ages 45-65.

Back at the Manny Cantor Center, on a recent Thursday, 20 people come from all boroughs of the city traveling by subway and bus, to one of the few places that has an evidence-based intensive English class (two three-hour sessions a week) with all older students. Many of the students have low levels of literacy in any language and never went to high school in their home countries.

Christine Green, the teacher, has been teaching English to adult learners for more than 20 years. She has had to adapt to her class – be less rigid, accept slower growth, allow them to make more grammar mistakes – to keep up their motivation. Her students who have been there for four years all started at level 0 and are now at a level 3 or 4. In her other classes, they would have mostly reached the highest level 7 with this level of commitment.

At a recent class, they dissected and took turns reading a passage about common misunderstandings in English. Even during the break, they copied sentences, used Google translate on their phones and wrote new words and their definitions. Since their English has improved, several of them have become volunteers at the center and brought other friends in.

“For me, it’s impressive. They make me see anything is possible,” Green, their teacher said.

Most of Green’s students are Chinese speakers. In New York, 92 percent of older Chinese speakers are less than proficient in English. Similarly, immigrants from Korea and the former USSR and Russia almost universally have low levels of English proficiency (94 percent and 91 percent, respectively). Older adults who speak languages that use the Latin alphabet (as English does) are more likely to have English proficiency. For example, 67 percent of older New Yorkers from Italy, Poland and Puerto Rico, are less than proficient in English.

Yumei Lang, who dreams of reading her mail, only joined the class a few months ago. She has since been able to read a letter that came in the mail for the first time, understanding that it was from a friend in Virginia who invited her to visit.

Eliena Wong says she can now speak enough English to call the police.

Another classmate, Frances Yip, 64, of the the Lower East Side, was a seamstress and raised three children in New York. She has been taking the twice-a-week English class for two years. She says her motivation comes from one incident several years ago when she went to the hospital for what turned out to be a blood pressure spike.

“My English was bad. They ask me a question. I had to wait a long time to find a person to translate. I felt very uncomfortable. It was hard to breathe. My children were at work. I called my sister to call an ambulance,” she said. “Then I recently hurt my hand. Most questions the doctor asks, I can answer.”

Another classmate, Wen Fei Liang, 64, came to the U.S. from China in 1991 to work in a garment factory. She has had polio since she was a child and relies on a wheelchair to get around the city. Since taking classes, she says, she can navigate her way on the bus on her wheelchair alone and get to the hospital.

“I communicate with my doctor. I can describe my symptoms and make a decision for me,” she says. “Before I just stayed at home. I couldn’t walk a lot. I’m more active now.”

Liang says her dream is to go to college, although for now she is content that she can help her 94-year-old mother, who lives with her.

“Now I can help my mother because I understand. I help my neighbor read English letter, and I help my neighbor make a doctor’s appointment using English,” she says. “Little by little. I’m learning.”

Veterans in the field say progress of the type Liang has enjoyed could be generated for a much broader segment of the non-English-literate senior population, but it will take some adjustment.

First, adult education for people of all ages must be prioritized before people reach older age, especially for women not in the traditional workforce, so that they do not arrive at older age, when it is harder to learn, without basic English proficiency.

Given that some people will need help when they are older, teachers will need to adjust their expectations on speed of progress and focus on students’ goals, says Green, who has been teaching English to adults for more than 20 years. Classes must be available where older people are in the majority to encourage participation and comfort, say older adults we interviewed. More flexible funding for English classes is needed that values outcomes like increased civic engagement or increased capacity to manage daily tasks, rather than only workforce outcomes.

A culture shift and new messaging that debunks ageist attitudes like “you can’t teach a dog new tricks,” attitudes which are absorbed by us all from childhood onward, are a big part of the picture. But so is money, starting with the city’s: By not building funding for older-adult English instruction into the annual budget, it appears and is a lesser priority, says the New York City Literacy Coalition.

Support for this article was provided by Rise Local, a project of New America NYC.

2 thoughts on “Older New Yorkers Have Huge and Growing Need for English Classes”

While it is certainly true that there are not enough publicly-funded ESOL seats available to serve limited English proficient New Yorkers, the article inaccurately reports that older adults applicants on waitlists for ESOL classes at LaGuardia Community College “are not called back.” In fact, all waitlisted English language learner applicants for LaGuardia’s ESOL classes are invited to intake and orientation sessions when seats are available, regardless of age or employment status. Furthermore, many students of all ages with civic and family engagement goals are currently enrolled in these free classes.

While sponsor-mandated eligibility restrictions apply on certain grant-funded projects, LaGuardia does not discriminate on the basis of actual or perceived race, color, creed, national origin, ethnicity, ancestry, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, or any other legally prohibited basis in accordance with federal, state and city laws.

Pingback: Our Program in the News | US Adult Literacy