Sadef Kully

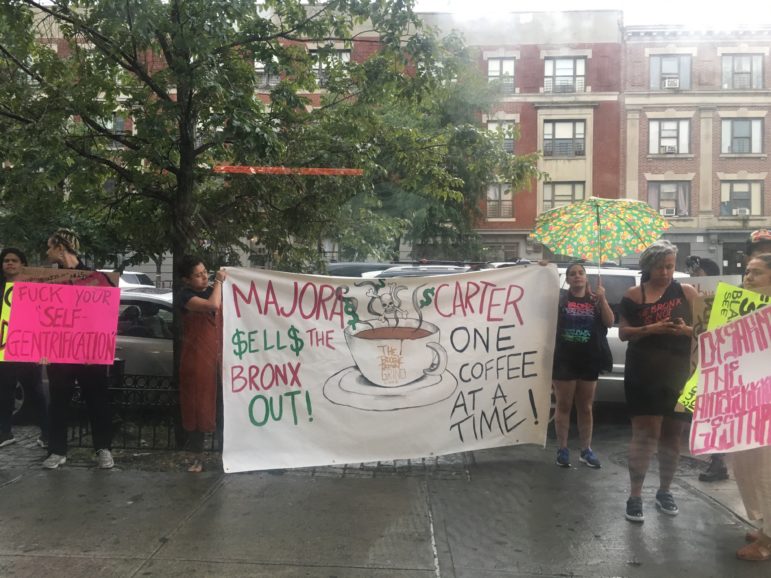

A protest last month by foes of Majora Carter and her bid for a ‘self-gentrification’ land trust made of South Bronx homeowners.

The development coming to the South Bronx has many residents and community activists worried about displacement and wary of signs that gentrification has taken hold.

But a few long-time Hunts Point residents—including environmental justice activist turned real-estate developer Majora Carter—have a different take: They want to “self-gentrify” and have proposed creating a land trust that would ostensibly capture some of the value created by rising property values.

Last month, Carter headlined an event sponsored by her own Hunts Point/Longwood Homeowners Community Land Trust working group, which includes four Manida Street residents including herself. A poster invited homeowners and small business owners interested in learning about “creating wealth, protecting your investment and/or growing your business.”

But others turned out as well. More than a dozen protestors from different groups showed up bearing signs and chanting “Sell out” while Carter stood smiling with a glass of wine inside a corner storefront on Hunts Point Avenue along with dozens of attendees. The protesters banged on the window, hoping the noise would deter the presenters inside from making their presentation. Some attendees were upset by the protestors. Others just shrugged their shoulders. Towards the end of the event, the police arrived but the protestors had left just a few minutes earlier.

“I call [the protestors] citizens against virtually everything or any changes,” said Carter. She denied that she was responsible for the interest that private investors have shown in the South Bronx. “People who follow real estate know people are looking at this [area] for a while.”

Carter, who owns a cafe on Hunts Point Avenue one storefront away from where the event was held, has long argued for “self-gentrification”—something she defines as “development by us and for us.”

A proposal, rejected

Carter emailed City Limits a week after the event and wrote that the Hunts Point/Longwood Homeowners Community Land Trust working group was “… a very informal association of like-minded homeowners in the area who are interested in supporting ourselves as well as future local homeowners-to-be.”

Carter wrote the group had submitted a concept paper to the city when the Department of Housing Preservation and Development requested proposals in 2017 for community land trusts.

A traditional community land trust is a model of non-profit land ownership in which a board of community stakeholders governs the use of land, while regulations ensure the permanent affordability of the rental or home-owner housing on that land.

Carter said her submission was not a traditional community land trust but instead a proposal to help current and at-risk homeowners gain back some control over their finances and maintain their hold on their current properties while creating additional opportunities through investment in the community.

“Hunts Point/Longwood Homeowner Land Trust Working Group (HPLT) mission is to provide an avenue for local homeowners and aspiring homeowners within the community to strengthen their ability and resources to re-invest and support local wealth creation,” Carter relayed by email. “HPLT members who currently own and are considering selling, will commit to offering right of first refusal to other local residents, at a fair market price.”

Read our comprehensive coverage

The HPLT proposal shared with City Limits in an email (you can see it here) was comprised of two pages and the details were vague. But what the proposal did focus on were on property owners’ investments rather than the traditional CLT which focuses on affordable housing. In the proposal, Carter listed the following as goals: “real estate investing, exploring available projected rehab and or rental subsidies, real estate tax abatements, technical assistance, marketing of units/properties, monitoring of compliance with terms of regulatory agreements, revolving loan fund to allow property owners to slow down and redirect real estate, transactions in communities of color toward maintaining current ownership or transferring to other local owners and workshops for aspiring homeowners, including financial literacy assistance to prepare neighbors to take advantage of resources and programs meant to reduce barriers to first-time homeownership.”

Carter’s husband James Chase said the best way to explain the “non-traditional” CLT was “taking at-risk properties and turning them around into profit-making investments for the community.”

Chase said “We Buy Homes 4 Cash” signs are sprawled all over the neighborhood, and seniors, especially older women who relied on their late husbands for financial decisions, become targets for real estate hounds.

“They (real estate agents) come and buy the house in cash. The widow does not know the value of her own home, how to pay bills or write a check—will sell for one third of the price. Our plan was to help those at-risk homes and help them create even more wealth. Help the lady rent out to a family in need or bring awareness to other folks. We are trying to educate and bring opportunities here,” he said.

In January 2017, the Request for Expressions of Interest (RFEI) seeking respondents interested in forming a Community Land Trust was divided by two categories to allow for two varying evaluations: “Developers” and “Non-Developers.”

According to HPD, the Hunts Point Community Land Trust submission was included in the “non-developers” category. The submission evaluation process had a minimum threshold criteria that CLTs were required to meet in order to move to the second phase of evaluation.

Carter’s proposal did not make the cut. The Hunts point CLT submission did not meet the minimum threshold criteria, according to a spokesperson for HPD.

“Of course, we knew that supporting homeowners in low status communities was way too radical for the city to consider, so no surprise we didn’t get it, but it helped us think about how we wanted to use our assets in support of our own communities,” Carter wrote in her email.

An estimated $1.65 million was granted to create and expand Community Land Trusts in the city through Enterprise’s new Community Land Trusts Capacity Building Initiative. The four main principles guiding the criteria were to design a CLT model that improved or filled the gap in the city’s existing affordable housing programs. The submission would also have to include the capacity to implement and operate a self-sustaining CLT, preserve long-term physical and financial health and a governance and financial structure, according to the HPD.

A lack of trust

Carter said right now the idea of her non-traditional CLT is on hold. Her event planned to discuss the CLT and maybe gain more members from the community but the topic was never even introduced after the protests began.

While some residents are loyal to Carter and her ideas, others are distrustful. Carter’s support for the controversial move of FreshDirect to the area created enmity among former allies.

Some Manida Street residents allege that Carter and developers, who own three homes on the block, want to rezone her block so that homeowners can build up and create additional income.

“For a lot people, it is a betrayal of sorts. It’s someone who came up with the community championing the community needs for open space and the environment and now this person is in development,” said Maria Torres, co-founder of the The Point Community Development and resident of Manida Street. “And at this point we want to know what her bottom line is.”

But Carter and her husband James Chase deny any scheme, noting that current homeowners can build up if they want because there is still room under the current zoning of the block. Carter’s company Majora Carter Group LLC has dabbled in real estate ventures such as the building restoration near the intersection of Hunts Point Avenue and Bruckner Boulevard in which Carter teamed up with Slayton Ventures and she also submitted a proposal for the abandoned Spofford Juvenile Detention center but the New York City Economic Development Corporation proposal was more appealing for the city’s affordable housing plan.

The Manida Street block is zoned for R6 which permits a diverse mix of building types and heights from small multifamily buildings to 13-story towers.

Some residents want to reduce those limits. Torres said Manida Street resident Jose Ortiz collected an estimated 50 resident signatures for the petition to make a request with City Planning to down zone the street to a R3, the lowest density zoning that allows semi-detached one- and two-family residences, as well as detached homes, in order to preserve the contextual character of their block. Torres allowed the residents to organize for the petition at The Point.

After the opening of the new Yankee stadium in 2009, private interest began to grow quickly in the South Bronx. There is development under way like the Mott Haven development site—two projects split over 1.3 million square feet that includes market-rate and some affordable housing—or the Bronx Point site, which is projected to bring 1,000 permanently affordable apartments into the South Bronx. Additionally, the city has opened up a new ferry route in Soundview and the state has moved forward on its much-debated $75 million renovation of the Sheridan Expressway into a Boulevard, which promises to decrease traffic congestion and create open space connecting to the waterfront. Meanwhile, the city is in the middle of conducting a Southern Boulevard planning study ahead of a possible rezoning. The study spans over 130 blocks and includes the Crotona Park East and Longwood neighborhoods and Southern Boulevard between the Cross Bronx Expressway and East 163rd Street including the Bronx River and Crotona Park.

“The big question is, who is the investment for?” said Gregory Jost, spokesperson for the Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association, which has worked to stabilize the area’s housing for four decades. “Our residents say they like the investments, too, but what kind of say do we have over how they invest? What we see is that the city is engaging folks as individuals as opposed to as a collective, and our interest is to have community voices at the table.”

Carter and her husband argue that her community is losing out on opportunities to reinvest back into the community,”I have seen these real estate guys pour over long list of properties with tax liens on them and then find those folks and buy them out,” said Chase, who says his and Carter’s goal is to help their neighbors stay and re-invest back in the Bronx.

The argument doesn’t sway ardent skeptics of development. “I think ‘self-gentrification’ is a silly term mostly used to justify gentrification by original residents who cover up the negative aspects and displacement of other original residents,” said Tom Angotti, professor for Hunter College in Urban Policy and Planning.

Torres said there are definitely residents from her community who support Carter because they fought with her for park space and other community needs. But Torres worries that Carter does not see the big picture where possible displacement and disappearing affordability are a reality for many single parent families in her community and her ideas are misleading to those who support her or those who are not aware of the risks at hand.

“For me, this is an issue that hits home. We want people from Manida Street to think about other parts of the community,” said Torres. “We all deserve nice things but sometimes we have to think about those things. We should be protecting and preserving parts of the neighborhood. Because, the reality is, once gentrification is started, it never really stops.”

5 thoughts on “What’s Next for Majora Carter’s ‘Self-Gentrification’ Hub in the South Bronx?”

‘One coffee at a time’?

Great piece. People fear what they do not understand. This is why homework is so important. I salute the effort and reach out to assist!

Self gentrification is the term that confuses me about her goals. It seems that she is saying that I am going to improve my neighborhood to displace myself. Tom is right, it is a silly term. We have an issue of city planning and community planning and between it, change. Progress is a complicated word and groups and city agencies define it in different ways. The economics definition is at times is self defeating, a reinforcing loop logic that sees progress as never ending. Sometimes what is overlook is the overall social, cultural, and biophysical Systems. Some see solutions by fixing parts that doesn’t do much to make the systems more resilient and healthy for people in that community.

Your sentiment that “she is saying that I am going to improve my neighborhood to displace myself” is pejorative and mirrored in the defeatist sentiment of the protestors in that it assumes people of color can’t possibly be successful and stay, reinvest, and prosper in place. “Planning”and academics have failed Ms Carter’s community to the point where she is attempting to put the property ownership wagons in a circle to fend off wave after wave of financial attacks on numerous fronts. Mr Tom has nothing to offer, and neither do you. Majora may not be able to save everyone, but your kind is guaranteed to save nobody.

Pingback: Banana Kelly Suggests Land Trust For Looming Southern Blvd Rezoning - This Is The Bronx