Abigail Savitch-Lew

Jumaane Williams and residents of East Flatbush held a press conference at 1509 New York Avenue on April 21, 2018.

On Saturday, Brooklyn Councilmember Jumaane Williams, residents and community board members of East Flatbush gathered outside a construction site to urge the Department of City Planning to initiate a contextual rezoning of the neighborhood. Contexual rezonings usually include height limits and other restrictions to preserve neighborhood character.

The construction site, at 1509 New York Avenue, will soon be redeveloped with an eight-unit, five-story apartment building. To local residents, especially homeowners, this structure and even taller ones slated for the area are examples of the kind of-out-context development that is encroaching on what used to be a neighborhood of one-to-two family homes. The local community board has long been asking for a contextual rezoning.

The push comes as several other neighborhoods throughout the city are calling on the de Blasio administration to provide zoning protections to prevent what they see as overdevelopment. Unlike the Bloomberg administration, which did work with communities—often higher-income ones in the outer boroughs—to design contextual rezonings, the de Blasio administration has prioritized growth of the housing supply and has been more reluctant to impose restrictions, whether for higher-income or lower-income neighborhoods.

Beyond disruption of the look and character of the neighborhood, residents described a number of problems stemming from development, including construction impacts like excessive noise and dust, harassment of senior homeowners to induce them to sell their homes, and an influx of residents without matching investments in infrastructure—or in parking.

“At one point, you can’t even own a car anymore because you have to park six blocks away,” said Yves Rene, President of FERN Block Association.

East Flatbush ranks 45th out of 59 community districts for the number of residential units within half a mile of a subway station, and almost 30 percent of residents depend on a car to go to work, according to the NYU Furman Center.

Residents also reported unscrupulous behavior by developers, such as the posting of fake “No Parking” signs and construction work without a permit. One resident spoke of being sued by a developer who said that for public safety purposes they needed use of her walkway for a construction shed. Attendees also emphasized that the new housing being constructed was not contributing to the affordable housing supply.

East Flatbush is a middle-income neighborhood with a median income of about $52,000 and the highest percentage of Black residents (almost 87 percent) in the city. In the 1960s and 1970s, it became home to many Caribbean immigrants seeking to plant roots through homeownership. Several residents talked about being longtime owners who were now disturbed to see its character transformed.

“We invested in these homes and we came here for a community, residential in nature,” said local Assemblymember Nick Perry. He explained that redevelopment would be acceptable if the new buildings were similar to the existing ones. “As the value of housing continues to rise…we hope that neighbors who are thinking of selling will be very picky about who they sell to.”

Williams also called attention to a letter mailed by Stephen Smith, a real-estate broker, to encourage homeowners to oppose “downzoning.”

“There are some in the community, including Councilmember Jumaane Williams, who are looking to restrict what can be built in East Flatbush,” the letter reads. “Your property would likely lose between $109,600 and $560,200 in value if rezoned.”

There are certainly others who would echo the case that restricting allowable development lowers property values. But Williams stressed that the real-estate broker didn’t have the community’s interests at heart and simply wanted to make money off the neighborhood. He also emphasized that residents were calling not for a “downzoning” but a “contextual rezoning”. (Generally, downzonings are thought to be rezonings that reduce allowable floor area in a given lot, while contextual rezonings impose rules on building height and shape.)

“Neighborhoods are going to change…but that change shouldn’t just happen overnight. There should be a gradual change that occurs to address the needs that we have now,” he says.

The councilmember, who said at the press conference he wanted the Department of City Planning to “speed fast the contextual rezoning—we don’t have five years,” also said that he’d be willing to look at affordable housing development in some commercial zones to serve people with the most need. A community board member similarly stated that affordable housing could be built, “on blocks and lots where it actually makes sense.”

NYU Furman Center

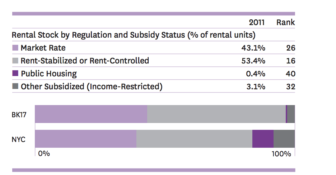

East Flatbush has a larger than average share of rent stabilized or rent controlled housing and a larger-than average share of market-rate housing, but little public housing or subsidized housing.

Hazel Martinez, president of the Four-in-One Block Association and a member of the board’s Land Use committee, said that while she didn’t disagree, as she knows the administration usually wants greater density on avenues in exchange for contextual zoning protections, she is concerned that the income-targeted housing required by the city’s mandatory inclusionary housing policy is not sufficiently affordable. And, she says, it seems like “communities with funds” never have to make concessions, while neighborhoods like hers have to accept overdevelopment, storage facilities and shelters. (As of last year, the community district did not have one of the highest ratios of residential beds to population, according to the City Council’s 2017 report, though a new shelter is currently under construction on Linden Boulevard. Martinez would rather see permanent housing built there instead.)

Williams, who voted against mandatory inclusionary housing and has repeatedly expressed concerns that the policy does not require units for the lowest income families, told City Limits that in exchange for allowing any additional development in the neighborhood, the city ought to commit to subsidizing more deeply affordable housing.

But other Brooklyn anti-gentrification activists, while recognizing the pressures on homeowners in East Flatbush, are wary of engaging in a city rezoning effort given what they say are the many precedents of neighborhoods not getting what they want from the rezoning process, and precedents of mayors pushing for large upzonings. They are hosting an event in East Flatbush in May with to inform residents about these risks.

“We can’t offer any lived experience that has been successful,” says Imani Henry of Equality for Flatbush, while Alicia Boyd of Movement to Protect the People warns, “They’re going to get a massive amount of development that they have not anticipated.” She also questions whether residents can get the level of restrictions that they’re hoping for without an actual downzoning, which she says the administration will never agree to.

As City Limits has written about at Zonein.org, stakeholders in Chinatown and the Lower East Side have long urged the de Blasio administration to move forward on a community-designed rezoning and have made limited progress. Another community planning process is underway in Bushwick, where it is still unclear how much the administration will be receptive to neighborhood demands. The administration was more receptive to Far Rockaway stakeholders, whose plan focused on increasing development, and to Councilmember Brad Lander and other Gowanus stakeholders, whose vision included growth for the Gowanus area.

The community board is holding a series of events to try to educate residents about the need for a rezoning. “We Shall Not Be Moved, R6 Zone Community Meeting” will be held on Thursday, April 26 at 7 p.m. at St. Stephen’s Lutheran Church, 2806 Newkirk Avenue.

10 thoughts on “Jumaane Williams, East Flatbush Residents Call for Contextual Rezoning”

If East Flatbush downzones from R6 to R3x or R3-1 then of course their homes will be worth less. But that’s the trade-off when you downzone. My S.I. neighborhood downzoned from R3-1 to R3x (for different reason than East Flatbush wants to downzone) in 2005/06 under Bloomberg. IIRC the whole process took about 2 years.

http://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/zoning/districts-tools/r6.page

http://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/zoning/districts-tools/r3.page

East Flatbush proponents do not want to downzone they simply want to protect the current zoning character ….that’s why they went out of their way to call it a contextual rezoning and NOT a downzoning.

It’s important to repeat their intentions when talking about this as it is easy to get people confused about motivations when you state the wrong thing online.

Generally, I support Jumaane Williams. I look forward to voting for him in the primary for Lt Governor. But in this instance, he’s wrong.

“Contextual Zoning” is, in a word, crap. It’s code for “I’m on board the life boat! Pull up the ladder!” Anyone who **really** endorses “contextual zoning” is advocating for all of us to live in tents or caves or maybe even that’s too much progress. I mean: once you’re living in a tent or a cave, who’d want anything else? Indeed, don’t add to the supply of tents and caves because we like it just the way it is. And always was. And always should be.

If you’re wondering, some views from my window are now obstructed by residential buildings that weren’t there when I moved into where I now live. There was noise and other disruption while these building were going up. That’s fine with me. It’s called “more housing”.

If reports of “unscrupulous behavior” (seemingly a euphemism for “illegal”) are accurate, these should be investigated by appropriate enforcement agencies. Penalize whoever is in the wrong.

The only way to achieve more housing is … wait for it … build more housing. Hiding behind “contextual zoning” is opposing more housing.

But even NYC has limited infrastructure. I’m sure CM Williams knows what his constituents want. We are a democracy. Williams is doing his job, representing his constituents wishes.

Contextual rezoning was explained quite well in the article why you are describing it as “downzoning” which it is not is curious to me, did you not understand the explanation in the article?

No one is asking for a down zoning which would in fact reduce property values as it would actually change the character of the neighborhood in the opposite direction.

NO, contextual rezoning means simply to apply imaginary limits on what can be built here going forward it is not about down zoning if any one can come along and build exactly the type of homes that are already here within the limits of the contextual rezoning.

Also, there is no reason to believe that contextual rezoning means “exactly as the house are now” it could very well allow for another floor level for every home as a possible limit, dramatically increase housing units in the neighborhood AND prevent extravagant shifts in character that come with housing with more than 3 levels.

Yours truly, resident East Flatbush.

I find it very interesting in so many different levels. Contextual zoning makes sense. If I am not mistaken CM Williams was Chair of Building and HPD Committee. The irony of how development can Impact a community in different ways bring to mind Karma.

Pingback: Today's Links: Photos of Brooklyn's "Rust Belt, Mental Health Murals & More - BKLYNER

interesting that when people of color (or not of color) who worked hard to earn a place in a nice. small-scale neighborhood, they accused of nimby bias, while the nyc real estate industry gets a pass and pockets the dough. also note there is already overdevelopment and the effect of new building will lead to a deterioration, hollowing-out, of nearby older, even well-maintained rental properties. that has consistently been the history of the ‘development’ and ‘redevelopment’ in the big apple.

Always good for laughs.

“Develop ” everywhere who needs prospect park plenty of space there to build just wasted currently. More people but not more parks sewer schools hospitals etc. Ludicrous.

Pingback: East Flatbush rezoning stalled more than 10 years ago. Is it time for another push? - The Brooklyn Home Reporter