Office of the Governor

Governor Andrew Cuomo

Albany has it tough this year. As a result of declining revenues, the state faces a $4.4 billion budget deficit that Governor Andrew Cuomo hopes he can eliminate by curbing spending growth to 1.8 percent and creating new revenue sources. Changes to federal health care funding may cost the state another $2 billion, and Albany is bracing for more federal cuts down the line. And then there’s fear that the federal tax bill, which reduces state and local tax deductibility, will cause wealthy residents to leave the state, resulting in declining tax revenue.

In his State of the State address on January 3, Cuomo emphasized the federal threats to New York. He also raised concerns about the state’s homelessness crisis.

“The homeless numbers are at record highs. And looking forward, with the Federal Government threatening to cut funding for homeless programs, it will only get worse. We must act,” he said. “The ultimate need, we know, is affordable housing and supportive housing and our budget has historic state commitment in these areas.”

Yet some advocates and members of the state legislature aren’t pleased with the offerings in the budget when it comes to housing and homelessness. The budget continues the third year of Cuomo’s $20 billion, 5-year Affordable and Homeless Housing Capital plan and includes other housing-related initiatives, but some advocates and lawmakers say the state needs to do more.

At a joint hearing of the State Senate and Assembly on Wednesday, city lawmakers and housing advocates raised concerns about funding levels for a number of different housing programs. In particular, several city lawmakers took issue with the budget’s lack of additional funding for the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). The state has appropriated $300 million over the past two years for NYCHA, but did not include any additional funding in this year’s proposal.

“We need the executive to sit down with the mayor and figure out a way of getting more money into the budget,” said Assemblymember Steven Cymbrowitz, a Brooklyn Democrat and chair of the Assembly’s housing committee.

There have also been concerns raised about the state’s contributions to managing the homelessness crisis. In a recent blog post, Shelly Nortz, deputy executive director for policy at Coalition for the Homeless, expressed concerns about a lack of adequate State investment in homeless shelters and a slow timeline for supportive housing development. The recently formed coalition Upstate/Downstate Housing Alliance, which includes groups like Make the Road New York, Metropolitan Council on Housing, Take Back the Land Rochester and others, also expressed their frustration with the budget and with Cuomo’s policy priorities in a press release last week.

“The governor’s budget is lacking common-sense initiatives that would actually get people out of shelters and allow families facing displacement pressure to stay in their homes: funding key provisions that would house the homeless and ensure repairs in public housing, and strengthening rent protections for tenants and expanding them across the state,” wrote the alliance, a statewide coalition of tenants, homeless New Yorkers, and owners of pre-fabricated homes.

According to Gotham Gazette, De Blasio also expressed the need for more efficiency from the state when it came to delivering supportive housing, affordable housing units and delivery of funding allocated for NYCHA. “We need to see that plan take off and start to have an impact on the ground in New York City,” De Blasio said of the governor’s supportive housing plan.

The governor did not respond to a request for comment on some of the advocates’ concerns. At Wednesday’s hearing, RuthAnne Visnauskas, Commissioner of Homes and Community Renewal (HCR) detailed Cuomo’s $20 billion, five-year plan, explaining that it aims to build or preserve 112,000 units of affordable housing, including 6,000 units of supportive housing. “The plan is a comprehensive approach to statewide housing issues and includes multifamily and single-family housing, community development, and rent stabilization,” she said. (The governor also has a 15-year plan for 20,000 units of supportive housing in total.)

Allocations of capital funding for the plan didn’t really begin in earnest until last year, the second year of the plan. According to Visnauskas, in calendar year 2017, 17,000 units of affordable housing were built or preserved. As for supportive housing specifically, about 1,000 of the planned 6,000 supportive housing units will have been financed by the end of this fiscal year, she said. While both figures might appear to put the governor’s plan behind schedule for 112,000 units in five years, the commissioner, speaking of the supportive housing plan, emphasized that the agency “anticipated there will be a ramp up” over the coming years.

The goal of the plan, according to the agency, is for 50 percent of the units to be in New York City and the other 50 percent of the units to be in the rest of the state.

Breaking down the budget

A state budget document explains that the $20 billion is supposed to include $3.5 billion in capital resources, $8.6 billion in tax credits and other allocations, and $8 billion to support operations of shelters, supportive housing, and to provide rental subsidies.

Since the governor’s plan was announced in 2016, it’s taken push from advocates to actually get capital funding for that $20 billion ball rolling. Advocates celebrated last year when the legislature appropriated $2.5 billion in capital funding for the plan, including, among other investments, $950 million for supportive housing, $472 million for new construction or adaptive reuse of low-income rental housing, and $200 million for NYCHA, on top of the prior year’s $100 million. In addition to that $2.5 billion, HCR also received a few hundred million for a range of housing programs, for a total of $2.8 billion total appropriation by HCR last year.

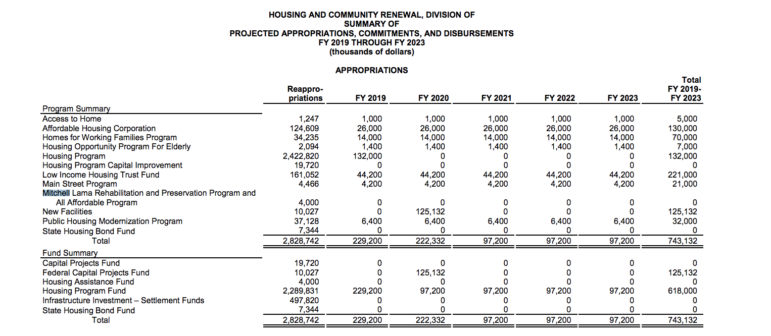

This year and in the following few, according to another budget document, HCR plans to appropriate much smaller amounts—one or two hundred million each year. This year’s budget, for instance, includes a $229 million capital appropriation for various housing programs, though more than half of that is not new money, but rather simply moved over from another part of the budget. There are no additional appropriations specifically for NYCHA planned this year or in future years.

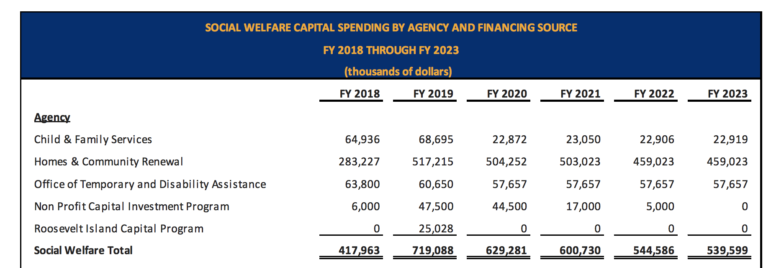

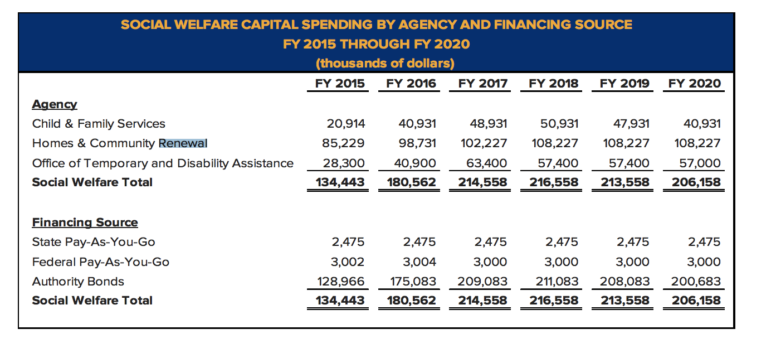

As shown in the charts at the end of this article, that big $2.5 billion lump sum from FY 2017 is intended to be spent over multiple years, with about $400 to $500 million to be spent by HCR each year. This year’s proposed capital budget for HCR includes $517 million in capital spending. By comparison, in FY 2016 and before the launch of the plan, the administration only planned to spend about $100 million a year on housing projects.

But Coalition for the Homeless’s Nortz expressed skepticism about the meaningfulness of the governor’s professed $20 billion investment. She says that beyond the $2.5 billion in capital funding from last year, plus some extra funding set aside for the operating costs of supportive housing and to cover inflation and caseload growth, she believes most of the $20 billion will simply cover commitments the government regularly makes.

“It would be helpful if the administration were more transparent about their budgeting and their planning and their allocations of funds because people get very confused and think the governor is spending $20 billion…[on] new initiatives,” she says.

The Department of Budget did not respond by press time to requests for a breakdown of the $8 billion in the plan that is supposed to support operations of shelters, supportive housing, and rental subsidies, or how it will be appropriated year by year. [See below for update.]

Demanding more than the plan

At the hearing, State Senator Brian Kavanagh, a Brooklyn Democrat, argued that as the state is trying to figure out ways to address other federal cuts, it has an equal responsibility to address the deficit faced by NYCHA as a result of years of federal—and state—divestment. But Visnauskas said that the state’s $300 million investment in NYCHA these past two years constituted “an incredible commitment on the part of the state.”

When State Senator Brian Benjamin, a Manhattan Democrat, asked whether $4.5 million for the Tenant Protection Unit, the same amount appropriated last year, was enough, Visnauskas said she believed it was, but that the agency would be happy to do more outreach in Benjamin’s district to inform tenants of their rights. Similarly, Assemblymember Michael Blake, a Bronx Democrat, questioned whether the state was putting enough funding into middle-income Mitchell Lama developments: the agency had received about $125 million to use over five years, according to Visnauskas. The commissioner replied that the agency believed the funds appropriated were sufficient to meet the needs of the Mitchell-Lama stock, but would be open to further conversations.

Advocates at the hearing pushed for a number of other things as well, such as investment in affordable homeownership and requirements that such funding be tied to permanent affordability restrictions, funding for accessible housing for the disabled, and the creation of a new tax exemption for community land trusts, among other demands. Several affordable housing advocates objected to a proposal from the governor to defer by a few years when investors can claim housing tax credits on their tax returns, which they argued would make those credits less valuable and diminish financing for affordable housing (the commissioner thought these concerns overblown). They also urged the state to consider “bifurcation”—a policy that would allow investors who are interested in state tax credits but not federal tax credits to only purchase the state tax credits.

The Upstate Downstate Housing Alliance wants the governor to embrace policy changes, including reforming rent regulation law to prevent the continued deregulation of rent-stabilized units. They also want him to create a “just cause” eviction policy, which would limit the circumstances under which tenants in market-rate apartments could be evicted, and a statewide law to prevent source of income discrimination, which would prohibit landlords from turning away tenants using vouchers and other forms of rental assistance.

The alliance has also called for at least $1 billion for NYCHA annually and funding for the creation of housing courts in other New York State cities besides Buffalo and New York City, which they believe will give tenants better recourse to address bad building conditions. In addition, the group supports the passage of Assemblymember Andrew Hevesi’s Home Stability Support legislation, a proposed statewide rent supplement to help renters who qualify for public assistance avoid eviction. And the alliance argues that the timeline for the development of 20,000 supportive housing units should be shortened from 15 to 10 years.

Whatever the duration of the plan, Nortz says, “We would like to see [the supportive housing units] funded all upfront because it costs more to build them later than it does now and because we have a terrible crisis on our hands.”

Nortz also expresses concern that in the past, the state has not done its fair share of contributing to the costs of providing New York City residents with rental subsidies and emergency shelter. According to the Coalition for the Homeless’s 2017 State of the Homeless report, in FY 2016 the state provided New York City with only 14 percent reimbursement of the cost of providing city rent subsidies. The report also says that while the cost of providing shelter to families in New York City increased by $435 million between FY 2011 and FY 2017, the state shouldered only three percent of this cost increase.* In addition, Nortz says the state also reimburses New York City for emergency assistance at a lower rate than it does other localities.

Budget documents indicate that state funding for New York City shelters remains at last year’s level, and that New York City will still be reimbursed at a lower rate for emergency assistance. The Department of Budget did not respond to Nortz’s concerns by press time.

Nortz was also concerned by Cuomo’s remark, in his State of the State address, that “some jurisdictions say case law prevents them from helping mentally ill street homeless. If that is their excuse, they should tell us what law stops them from helping sick homeless people and we will change the law this session.” Nortz said that in further conversations she learned the administration was considering changing a law to make it easier to remove homeless people and take them to hospitals or shelters against their will, a move she strongly opposed.

“The surest way to make people hide better and remove themselves from human services and support is to aggressively approach them with the police and do things to cause them to be relocated against their will,” she argues.

A challenging climate

In the current climate of fiscal uncertainty, left-leaning commentators are encouraging the governor to put forth a more ambitious plan to raise taxes. Republicans are fighting for exactly the opposite. The Upstate/Downstate Housing Alliance is of course on the former side, seeking new revenue sources to pay for increased housing investment. Alliance members have long called for reform to the carried interest loophole, a tax benefit received by private equity investors, and for changes to make the state’s income tax system more progressive, with higher taxes on millionaires.

This year the governor has in fact called for eliminating the loophole as one of his revenue-generating strategies. But getting the governor to commit to more progressive income taxes this year may be a challenge. Last year, Cuomo agreed to renew the current surcharge on millionaire’s taxes until the end of 2019 but wouldn’t go so far as increasing that surcharge. And this year it will be even more difficult to raise taxes on the wealthy, says David Friedfel of the Citizens Budget Commission, with some lawmakers concerned about losing wealthier taxpayers to other, lower-tax states. New York is heavily dependent on its wealthy: Taxes paid by the highest-earning one percent of New York State taxpayers make up about 40 percent of total personal income tax receipts. Much about the future of New York State’s tax system remains uncertain, with the governor exploring the possibility of switching to a payroll tax system.

But Paulette Soltani of Vocal New York, a member of the Upstate/Downstate Housing Alliance, rejects the logic that Cuomo should be driven by fears of wealthy people fleeing the state.

“Some of the wealthiest people in our state support responsible tax and budget policies. What he should be concerned about is how to keep people in their homes and out of the shelters and streets. New York is losing residents due to lack of affordability and economic opportunities. We need major investments to turn our state around, and that can happen if the wealthy pay their fair share,” she wrote in an e-mail.

Yet Cymbrowitz told City Limits he’s not optimistic about prospects for large additional housing investments in this year’s budget.

“We were extremely successful last year with $2.5 billion dollars in housing. I wish that we could replicate that this year, but with all the budget issues, we certainly can’t do that,” he says.

But he says the Assembly Democrats will continue to look for ways to secure additional resources for NYCHA, ensure that the Republicans don’t take out funding for the Tenant Protection Unit, and continue developing the Home Stability Support legislation. He’s also seeking funding streams for his own Elder Rental Assistance Program legislation, which would create a voucher program for seniors.

Although advocates are pushing for reform of rent stabilization law immediately, it seems more likely that the state legislature will wait until the current rent laws expire in 2019. “We will continue to work on [reforms] this year in preparation of next year,” Cymbrowitz says.

The Governor’s 2018-2019 Budget, By the Numbers

State Department of Budget Capital and Financial Plan FY 2019

This chart shows proposed appropriations for HCR from FY 2019 through FY 2023. The row “Housing Program,” column “Reappropriations” contains the $2.5 billion from last year’s budget.

State Department of Budget Capital and Financial Plan FY 2019

This chart shows planned capital spending from FY 2018 through FY 2013 for several social welfare agencies. The row “Homes & Community Renewal” indicates the planned spending on housing projects over time.

State Department of Budget Capital and Financial Plan FY 2016

This chart is from the FY 2016 budget and gives an indication of how expected spending levels for HCR have changed since the announcement of the $20 billion plan.

Update: According to the Department of Budget, most of the rest of the plan (besides the $2.5 billion in capital projects from 2017) is not new funding above existing levels, but a solid commitment to continuing the state’s existing housing-related spending for five years in the face of other competing budget priorities. So, about $1 billion (in state capital funds and settlement funds) will go to base capital programs—that is housing-related programs that fund projects that construct or upgrade buildings, and which the state funds annually. About $8.6 billion is federal tax credits and bond allocations will support housing projects and is what the state traditionally has access to, except for an extra $200 million for supportive housing. And then there’s $7.5 billion for base level spending (for programs the state usually funds annually) on shelters, supportive housing, and rental subsidy programs. The $20 billion mix also includes some other settlement funds, state capital appropriations, NYC rent subsidies funded by the state, and state low income tax credits.

*Correction: Originally said the cost of providing shelter increased by $435 billion, instead of the correct $435 million. Also, that’s just the cost of providing shelter to families, not single adults.

2 thoughts on “Cuomo’s Housing Budget Must Go Farther, Some Advocates Say”

The fact of the matter is that nothing is really being done to REALLY assist the homeless, or, the poor! When you have people who would rather freeze sleeping in the streets, than to be in a shelter indicates how dire the conditions are in them. They are filthy, & you run a risk of being assaulted, & whatever meager possessions you may have stolen. I’d rather die in the streets, too! What compounds this desperation, is when you have children, or, pets, who provide many with comfort, & you can’t provide them with a hot meal, clothes, & proper healthcare.

I’m starting to lose faith in our elected officials, for not cutting through the “proverbial red-tape”, & just letting people have a safe, clean place where they can, especially the children, lay their heads down & rest, it’s their given right! I’ve heard the mumblings & grumblings of the well-to-do, saying they’re sick & tired of having to foot the bill for the poor, of taking divisive actions, for example: putting up barriers, designating zones where the poor are not allowed to walk, eat, or, visit unless you are of a specific group. Add to this the absurd “Congestion Pricing Plan” being touted by Mr. Cuomo. It’s insane to me, that my husband & I were born & raised in Manhattan, & to drive below 59th Street, we must pay!!! Take the money from the Powerball, Lotto, & all the stupid games, & give it to “45” for his damn wall, or, use it to build decent shelters, & sanctuaries for abused animals, & stop taking people’s money, giving them false hopes while draining the few pennies they have left buying tickets that are never going to amount to anything, that’s where the real crime is!!! When you think like this, please be reminded, that many came from other origins to “the land of opportunity”, that clearly states, “give me your hungry, your poor……………..” We’re not all asking for hand-outs, but, simply to be given the resources/contacts necessary, sans all the red-tape, to provide for our loved ones. Greed is what’s impeding progress. Last, let me just use my beloved Puerto Rico as a glaring example. Four months after the hurricanes, thousands are still without basic necessities!!!!!! They are our American brothers & sisters!! It’s sad & inhumane! God Help Us!

Pingback: Housing Is the Key to Unlocking Andrew Cuomo’s Political Ego – The News Pro