JobsFirstNYC, from the "Innovations in the Field" series

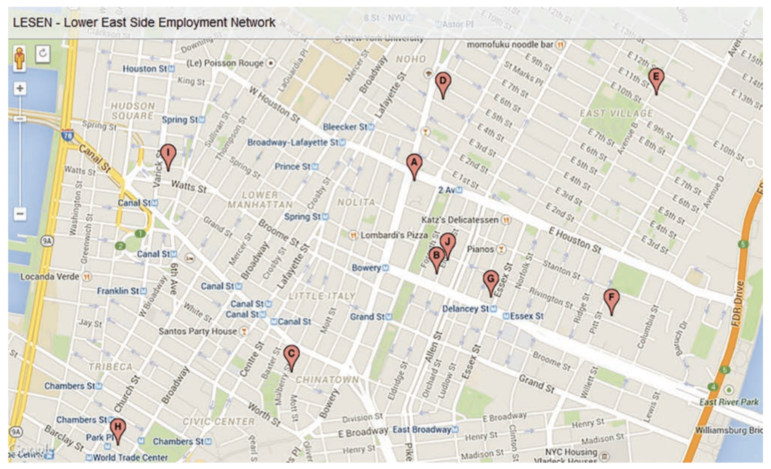

A 2015 map of partners in the Lower East Side Employment Network

In low-income communities throughout the city that are discussing large development projects or neighborhood rezonings, residents frequently demand guarantees of local hiring. It’s a concern of obvious importance—a matter of ensuring wealth generated by neighborhood change is distributed equitably. And it’s especially relevant where new development threatens to exacerbate displacement pressures for existing low-income residents. If such residents stand to benefit from the development coming to their neighborhood, so the thinking goes, they’re a little more likely to resist displacement pressures. That’s true when there’s a job in the offing and truest, of course, when the job provide a decent wage.

In answer to these concerns, the Blasio administration often touts the recently expanded HireNYC program, which sets hiring standards for employers that are doing business with or receiving certain kinds of financial support from the city or that are tenants in certain city-managed or city-assisted developments. But that program, while important, has a limited scope: developers who are not receiving financing from the city and are building on private land face no requirements, though they may choose to work with city or non-profit workforce providers in the area.

That’s where the concept of a workforce referral network comes in. The idea was first spearheaded by an alliance of workforce and training nonprofits as well as Community Board 3 in the Lower East Side. In 2007 they formed the Lower East Side Employment Network (LESEN), which serves as an entry point for any employer in the neighborhood seeking to find workers, and also fosters collaboration and resource-sharing between each of the participating organizations. An increasing number of neighborhoods are following suit, and Comptroller Scott Stringer’s office has become a strong advocate of the model and is spreading the word throughout the boroughs. The mayor’s Office of Workforce Development has been brought in to help facilitate the creation of such a model in the Jerome Avenue area, where a neighborhood rezoning is under consideration.

Of course, creating a better local hiring system may not ameliorate all a community’s concerns about a rezoning. Nevertheless, it’s worth looking into how the LESEN model works, what are its strengths and weaknesses, and how it can be applied to other places.

Moving beyond competition

LESEN is currently a collaboration between Manhattan Community Board 3 and eight community-based workforce organizations including the Chinese American Planning Council, Good Old Lower East Side, Grand Street Settlement and others.* The network was founded in recognition of the fact that the neighborhood, which in 2000 was among the top ten community districts with the highest unemployment rates, was undergoing an economic upsurge. According to the comptroller’s neighborhood economic profiles, from 2000 to 2015 the number of businesses in the neighborhood grew by 25 percent, from 6,834 to 8,561.

The workforce organizations realized that rather than competing with each other for the attention of new employers, they could establish a collaborative conduit for job training and placement. Thanks to funding from JobsFirstNYC, an organization that addresses youth unemployment by supporting partnership models throughout the city, the partners were able to hire a full-time coordinator in 2012.

“These are nonprofits getting together to say: If there’s this economic development coming to our neighborhood, and employers are seeking talent locally, then they’ll have a single point of entry,” says Marjorie Parker, executive director of JobsFirstNYC.

What makes LESEN unique is its strong connection to employers. The coordinator serves as the main contact for employers, informing the workforce nonprofits of business needs and pre-screening candidates referred by those organizations before sending them for an interview.

The spirit of partnership is also key. As part of a single network, the workforce organizations are able to refer clients to their partners if they cannot meet those clients’ needs. When the community board learns of a project, it refers the employer to LESEN rather than having to pick a single workforce provider and be perceived as picking favorites among the workforce nonprofits.

Agreeing to work with LESEN can actually be beneficial for an employer. For one, LESEN can make an employer’s life easier by providing a ready stream of candidates who, because they work locally, are more likely to show up on time. And then there’s the issue of public face.

“There may be a benevolent component but also a marketing, public relations component and definitely a community relations component,” says LESEN coordinator Gaspar Caro.

Susan Stetzer, district manager of Community Board 3, says that when a company approaches the board seeking a liquor license or some other type of permission, it’s usually her policy to tell the employer about LESEN after—not before—the board has voted on the project. “I think licenses and approvals must be on its own merits,” she explains.

For large and important projects, sometimes the board does include LESEN in an approval agreement. For instance, when voting to approve the application for the redevelopment of the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area, the board noted in their conditions that the city must require the developers to fund the Lower East Side Employment Network to support training for local residents.

Measuring LESEN’s success

There are signs that LESEN is working as a method to promote local hiring, though there are also limits in what has been measured.

Since 2012, LESEN has engaged 170 employers and facilitated 1,600 interviews that lead to 540 hires. According to a 2015 report on LESEN by JobsFirstNYC, organizations that are involved in LESEN each saw a roughly 10 percent annual increase in their outcomes as a result of the network’s activities—a figure Parker of JobsFirstNYC says is expected to increase. For instance, the Chinese-American Planning Council’s hospitality program expanded from about 80 to 100 graduates a year as a result of working with LESEN.

In most cases, LESEN provides candidates but doesn’t form a specific agreement that the employer will hire a certain number. The exceptions are four projects in the neighborhood where LESEN has signed memoranda of understandings with the employing project: Hotel Indigo, the expansion of the Public Hotel on Chrystie Street, the South Street Seaport expansion, and Essex Crossing (previously known as the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area).

Caro says that the memorandums are tailored to each project: Some have included stipulations that 30 percent of hires are made through the network.

“It’s striking a balance between being realistic on what local workforce providers can deliver, in terms of the scale [and] the number of candidates, and what the community hopes to achieve,” he says of the 30 percent target. Caro estimates that the employers engaged in these memorandum that require 30 percent hire have been meeting that goal, but says he doesn’t know the exact percentage achieved.

“There are definite means of keeping track of whether the employers are meeting their goals laid out in the MOUs, we regularly report LESEN’s outcomes with various companies and projects to the community board. However, difficulties stem from the reality that the employers’ overall staffing levels fluctuate seasonally and due to economic or other labor market trends; it’s also labor-intensive and challenging to consistently, precisely track these,” Caro said in an e-mail.

The Essex Crossing memorandum does not specify what percent of hires must be made through the network, but did entail a “first look” agreement, which will allow LESEN to be the first to screen clients for permanent jobs associated with the development. As a city project, the developers of Essex Crossing are actually required to meet HireNYC goals for permanent jobs, and LESEN has been engaged as a “community partner” to help the developer actualize those goals. In addition, Essex Crossing partnered with LESEN to pilot a construction training program and LESEN has made successful referrals for construction jobs.

And how well-paying are these jobs attained by locals through LESEN? From 2012 to 2014, the average wage of employees hired through LESEN was $10.61 per hour, about a dollar per hour more than placements made through the city’s Workforce1 Career Centers, according to another JobsFirstNYC brief. Caro says LESEN often partners with businesses that pay higher than the average for their sector, like boutique hotels. Today the LESEN average wage is $13.85 per hour—what amounts to about $29,000 annually.

“It’s still not a [living] wage” in New York City,” Caro says. “But it’s still hiring individuals who have had barriers to employment in the past and it’s a foot in the door.” He adds that LESEN is also working toward providing more pathways for higher-paying careers, and that one partner, Good Old Lower East Side, recently began providing construction safety training.

Spreading the model

The movement for a LESEN-like model has taken off in other parts of the city, and in each new place the model takes a somewhat different form. In 2014, East Harlem Community Board 11, Union Settlement Association, STRIVE and other local organizations launched their own collaborative, the East Harlem Talent Network (EHTN) with funding from the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone. EHTN works similarly to LESEN, but includes a huge network of organizations both inside and outside Upper Manhattan.

“We work with over 120 community based organizations that provide a slew of training programs and resources and services,” says director Adriane Mack, explaining that many East Harlemites take advantage of services outside their neighborhood due to the stigma of being seen by one’s neighbors at local organizations. EHTN asks the 120 partners to send them candidates who live in Upper Manhattan and East Harlem.

More recently, JobsFirstNYC helped create a workforce network in Staten Island composed of local organizations like Empowerment Zone and African Refuge that are dedicated to reducing the population of out-of-school and out-of-work 16- to 24-year-olds on the island. That network places a special emphasis on providing education, training and wrap-around services to cultivate talent in youth. Conversations about replicating the LESEN model are now underway in Bedford Stuyvesant, in Hudson Yards, in the Lower Concourse, and in Flushing, according to Parker of JobsFirstNYC.

The approach is catching the eye of government as well. In May, Stringer released a report documenting tremendous growth in the number of city businesses, especially in the outer boroughs and in low-income neighborhoods, but noting continued high unemployment rates in such neighborhoods. The report’s first recommendation was to fund a network coordinator in every community district in the city and establish workforce referral networks based on the LESEN model. The comptroller’s office hosted an event in Brooklyn to share the LESEN-model more widely; they are planning future events in the Bronx and Queens.

The comptroller’s office says they’re seeing some interest from the de Blasio administration as well, particularly from the Office of Workforce Development, which was created by the administration in 2014 and is spearheading the administration’s plan to shift the city’s workforce strategy away from a focus on job placement and towards creating pathways to middle-class careers. The comptroller’s office hopes the LESEN strategy can be one of the essential components of the de Blasio administration’s workforce strategy.

Those who are familiar with the LESEN model, however, know that it’s easier said than done.

“It’s really hard work. Workforce development in general is really hard work but…in a collaborative entity like ours, it really starts with a lot of [unfunded] efforts,” says Caro. He said it’s important to have not only a full-time coordinator, but committed liaisons employed at each of the member organizations.

For Parker, the success of the model depends on the recognition, by both the city and businesses, that successful workforce referral systems require dedicated funding to community organizations that lack financial resources but possess tremendous local connections. In addition, Parker and others emphasize that success is contingent upon early transparency from the city about what economic development projects are on their way—and she praises the Office of Workforce Development’s work in the Jerome Avenue as a good example.

A model for rezoning neighborhoods?

At the request of Community Boards 4 and 5 in the western Bronx, who last year expressed interest in creating a LESEN-like model in conjunction with the proposed Jerome Avenue rezoning, the mayor’s Office of Workforce Development is now helping to organize such a collaborative.

“It’s very much lead by the community organizations,” says Ashley Putnam, an economic development advisor at the Office of Workforce Development. “It really takes community buy-in…It’s not like, ‘Here’s a formal structure, put it in place and it works.’”

Local organizations have spent the last couple months engaging in exercises like “asset mapping” so that they can learn about each other’s strengths. For instance, Bronx Community College has a construction training program and Sustainable South Bronx has a Green Jobs program, while Part of the Solution offers free showers, food pantry and case management services. By getting to know each other’s programs, the different organizations will be able to make appropriate referrals for clients they are not able to serve. JobsFirstNYC and LESEN have also shared guidance with the new group.

“There definitely seems to be some energy and momentum by [community based organizations] and other institutions in the neighborhood to hire even more local jobseekers, or provide training to better equip them for good-paying job opportunities,” said Kerry McLean of the Women’s Housing and Economic Development Corporation (WHEDco), another participant in the Jerome Avenue effort, in an e-mail. She also tells City Limits that the fact that the neighborhood may face a rezoning makes it especially important to think about “how to anticipate what workforce needs will be in three and five years.” City agencies can be helpful, McLean says, by providing local organizations with insight about what economic trends to expect over the course of the rezoning.

Another participant in these networking discussions is the tenant’s rights group CASA New Settlement, an organization that has been critical of the rezoning—concerned about both the affordability of the new apartments the rezoning will generate, as well as whether the city is prepared to ensure the rezoning results in real economic opportunities for local residents. Director Sheila Garcia says she thinks there are aspects of the LESEN model that might be useful, but that Jerome Avenue needs other initiatives too, which might warrant some kind of hybrid, new system.

“I think we would need a more holistic approach that encompasses more options other than access to jobs—more around training, more around a pathway [for] change of jobs,” she says.

Of course, LESEN’s partners do in fact provide some training programs, and each rendition of the model has been different, but the model is best known for its “employer-facing” approach—it’s emphasis on supplying candidates to meet the demand for employees. Garcia says the western Bronx will need a system that takes into account its residents many barriers to employment, with wraparound services, financial literacy programs, training initiatives focused on adults—especially adults without English proficiency–and resources specifically for autoworkers who will be affected by the rezoning. Furthermore, all this must happen fast, in order to take advantage of changes that could potentially be coming to the area, she says. She also wants to see the city engage with more partners and community members to build the network, as well as efforts to ensure the rezoning doesn’t just bring low-wage retail jobs, but also pathways for existing residents to higher-paying jobs.

“The LESEN model seems amazing and seems like it’s working, but we would need to create something that’s a little different from that,” she says.

LESEN, HireNYC, and Community Board 3 will host an informational meeting on retail jobs coming to Essex Crossing on Wednesday, November 15 at 6:30 pm, Seward Park High School Auditorium, 350 Grand Street.

*Correction: There are eight (not seven) non-profits in LESEN. They include Good Old Lower East Side, CMP (formerly Chinatown Manpower Project), Grand St. Settlement, Henry Street Settlement, Educational Alliance, The Door, University Settlement and Chinese-American Planning Council.

2 thoughts on “Workforce Referral Networks: The Hot New Approach to Local Hiring”

This is hardly a new concept. Politicians have been pouring money into nonprofit “workforce” agencies for years; the vast majority of jobs offered are minimum wage seasonal retail work.

How can these workforce development agencies be improved? And/or is there a larger structural issue that needs to be addressed first?